by Robert Johnson

The Port of Bellingham and the Washington state Department of Ecology have expedited the cleanup of toxic industrial chemicals embedded in the soil and groundwater of the Waterfront District under pressure from one of the port’s tenants.

The rapid pace of development on the waterfront is driven by the boat construction company All American Marine, which needs a new and larger facility to handle the construction of bigger, more profitable boats. AAM leases its current building in Fairhaven from the port and threatened to leave Whatcom County if a new building was not quickly completed, said Matt Mullet, CEO of AAM.

A key element of the speedup is using the new AAM building now under construction on the central waterfront site in Bellingham as a cap to contain a portion of toxic soils in the landfill located on the premises, leaving the rest of the site — the majority of the whole area — to be dealt with later. Using a building as a cap is a fairly common practice around the country. But in this case, there is still no answer as to the scope of the whole site remediation and the potential risk for toxins to leach into the nearby lagoon and ocean.

Washington state’s 1996 Model Toxics Control Act requires developers to address toxic chemicals contaminating the site before beginning construction. Starting in the 1940s, land on the site was used for heavy industrial purposes, polluting the site’s soil and groundwater with arsenic, lead, mercury and petroleum. The site also contains remnants of a city-owned landfill, which poses difficulty for remediation of the site. Methane produced by the landfill could potentially build up to explosive concentrations below any new building.

According to the interim action work plan for the site, “Soil impacts have been identified in the area of the AAM project and pose potential risk to site workers and the public via direct contact and indoor air inhalation. Site-wide remedial alternatives are currently being evaluated in the [remedial investigation/feasibility study]. However, due to the port’s development schedule, soil impacts in the immediate area of the project will be addressed as interim cleanup action.” [Emphasis added.]

“Right now, we’re focused on the successful completion of the All American Marine project,” said Mike Hogan, the port’s public affairs administrator. “We have a pretty ambitious timeline to get it done by the end of the year.”

The language used in the interim action work plan is consistent with the overall goals of the cleanup, which focus more on the completion of the facility than the elimination of toxic chemicals.

“We at Ecology help to facilitate development; we don’t want to harm the economy,” said the site manager, Brian Sato.

Interim Action

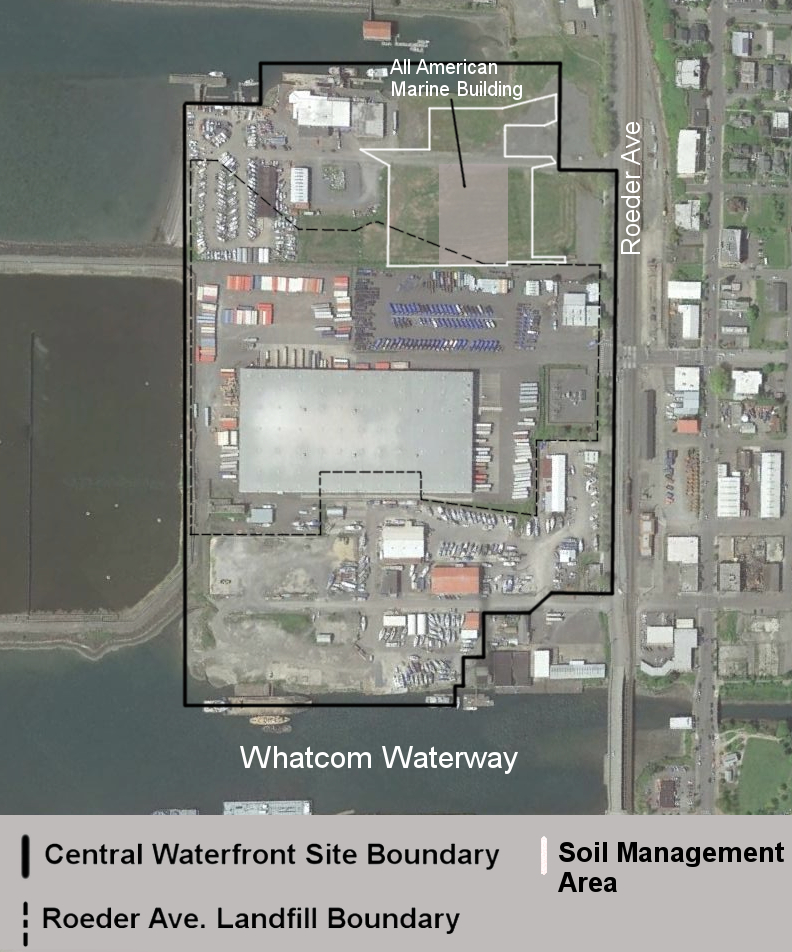

The site is comprised of four subsections: the Chevron subarea, Colony-Wharf subarea, Olivine Upland subarea and the Roeder Avenue Landfill Refuse subarea. The new AAM building straddles the Roeder Landfill and Olivine subareas.

In 2013, DOE consolidated the four subareas after it discovered “commingled groundwater contamination.” Interim cleanup action, however, will only be undertaken on portions of two of these subareas to allow the construction of the AAM building.

Interim action differs from a cleanup action in that it only addresses partial cleanup of a site. The distinction is used to justify cleanup of land essential for the construction of projects like the AAM building while ignoring site-wide contamination.

It is not unusual for DOE to oversee interim action before a final cleanup can be achieved, said Eleanor Hines, lead scientist with ReSources Bellingham.

“[Interim actions] typically are done because there is some kind of urgency,” Hines said.

In 2006 the city and the port entered into a legal agreement with DOE which required complete investigations of toxic waste on the site and to carry out the necessary cleanup. The site was largely untouched until 2016, when the port needed the new facility to retain its tenant.

“Development and cleanup go hand-in-hand because the development facilitates the cleanup,” Sato said. “One is a catalyst for the other.”

Yet, in this case, development and the interim action are so interconnected the interim action is being used to speed development interests.

An overhead view of the central waterfront site. The site is northwest of downtown Bellingham, adjacent to the railroad tracks at the intersection of Roeder Avenue and F Street.

Remedial Investigation/Feasibility Study

DOE’s website defines a remedial investigation/feasibility study as “an in-depth study conducted to: determine detailed site characteristics and define the extent and magnitude of contamination; evaluate potential impacts to human health & the environment; establish cleanup criteria; and evaluate cleanup alternatives.”

Even lacking definitive studies and data, DOE authorized construction to begin in June 2016 on the 51,200-square-foot All American Marine facility as part of the interim cleanup action. Construction is ongoing, with expected completion by the end of 2016, although DOE has not yet finalized the remedial investigation/feasibility study on the site.

Without a finished remedial investigation/feasibility study, DOE must rely on 15-year-old data and soil samples unrepresentative of the entire site to understand the extent of the contamination.

Construction of the Building and Cleanup Action

The interim action plan states, “The Site is currently within the [remedial investigation/feasibility study] process; therefore, Ecology has not yet established final cleanup levels for the Site. However, the [interim action] areas are defined based on soils located within the project footprints and extent of excavation required for construction purposes.”

As part of the interim action, 6,800 cubic yards of soil will be excavated to install utilities underneath the building. That excavated soil will be tested for toxins by DOE at the frequency of one sample per 200 cubic yards of soil.

“The building will isolate and remove contaminated soil as necessary for construction,” according to the central waterfront toxic cleanup website.

Samples will be taken from soil found directly underneath the building, tailoring the cleanup to the needs of construction. DOE will not test soil throughout the site, which could be more contaminated than soil under the AAM building. Again, without a finished remedial investigation/feasibility study, DOE cannot predict the final cleanup levels for the site, which might differ from those beneath the building.

The situation could be made worse because the AAM building will be placed on top of contamination and used as a cap over its section of the Roeder Avenue landfill. The facility will be equipped with a ventilation system to control the buildup of landfill gas under the building. This particular system expels gas into the atmosphere.

Without a completed remediation/feasibility study, DOE is relying on data obtained by ThermoRetec Consulting Corp. in 2001 to determine the rate at which the landfill will produce gas. The port hired Landau Associates, a Seattle-based environmental engineering consulting firm, to input that data into the Landfill Gas Emission Model. Its researchers estimated the current amount of landfill gas emitted for the entire landfill to be 25 cubic feet per minute. The AAM building will cap only a portion of the landfill area, and its ventilation system is designed to handle 1.4 cubic feet per minute of landfill gas, according to the interim action work plan.

It’s uncertain, given how old the relevant data is, that this ventilation system will be able to handle landfill gas buildup on-site.

“It’s always nice to go back and check, especially when the study is 15 years old,” Hines said. “[The port] felt extremely confident that the methane levels had decreased, but it’s hard to know without actually looking.”

On top of that, if the feasibility study later finds higher concentrations of landfill gas or toxic chemicals in the soil than originally foreseen, the port and DOE will have a completed facility on the site that could impede the final cleanup.

A 1996 study by DOE found groundwater concentrations of chromium exceeding cleanup levels flowing from the Roeder landfill into Bellingham Bay and the Whatcom Waterway, a canal bordering the south side of the site. The flow of groundwater from the site is still an issue today, and the interim action does not address it.

In 2012, another interim action on the site fixed a failing bulkhead which was allowing petroleum to leak into Whatcom Waterway. During that interim action, DOE addressed the site-wide groundwater contamination in response to a public comment, saying, “The discharge of contaminated groundwater into Bellingham Bay is a key component of the remedial investigation effort at this site and will be fully evaluated and reported in a remedial investigation and feasibility study report.” The study was to be completed in 2013.

As of July 2016, however, DOE still has not completed the study and has yet to develop a plan to remediate the groundwater contamination. Construction of the AAM building apparently has taken precedence over a pressing issue that was identified 20 years ago.

Ranking

The entire Bellingham Bay cleanup targets 12 separate sites, but the site has received special attention from the port and DOE, which uses a 1-to-5 scale to rank the dangers posed at a toxic waste site, 1 being the most hazardous. The Bellingham Bay cleanup project encompasses multiple rank 1 sites, such as the South Street Manufactured Gas Plant and the Weldcraft Steel and Marine site. Yet, interim cleanup has begun at the site, which was ranked at 2. This was done to complete the AAM building and retain the port’s tenant, while ignoring sites that, based on DOE’s own ranking system, are in greater need of cleanup.

Funding and Development Goals

The cost of the cleanup effort for the site alone is estimated at $10.37 million and funding has been made possible by a $3 million loan/grant from Whatcom County, drawn from the Economic Development Investment Program.

The port applied for this program by naming the construction of the AAM facility a “Jobs in Hand” project. These types of projects allow for immediate creation and/or retention of jobs by providing public infrastructure that will directly support jobs, according to the program’s application waiver.

Although the building is intended for AAM, a private business, the facility will still be considered public infrastructure since it will be owned by the port and leased to the company. With an expanded site, AAM plans to hire about 30 more employees.

Currently, the port’s operations employ 5,537 workers, making it the largest employer in Whatcom County, according to their website.

________________________________________________

Waterfront Cleanup History

1996: Federal, state, tribal and local governments form the Bellingham Bay Demonstration Pilot team to develop a bay-wide approach to clean up contamination, control pollution sources and restore habitat. The team is managed by the city and the port and is led by DOE.

2000: DOE publishes the Bellingham Bay comprehensive strategy and final environmental impact statement, which was to be used to guide future cleanup and development.

2006: The port enters into an agreement with DOE to conduct a remedial investigation/feasibility study at the central waterfront site.

2013: The port and the city unveils the Bellingham waterfront district redevelopment master plan, detailing the potential projects on the waterfront and development goals.

2015: The port announces in June its plan to construct a new pier and a new building on a segment of the waterfront in Fairhaven housing All American Marine and the Fairhaven Shipyard. This project would have allowed both companies to expand, but was contingent on grants through the Model Toxic Control Act. The port did not receive the anticipated funding and the Fairhaven expansion project was scrapped. The port works to find a new site that could host a larger facility for All American Marine.

2015: The port announces in December the new location of the All American Marine building on the central waterfront site.

2016: Construction begins in June on the All American Marine building.

________________________________

Robert Johnson is a writer and editor interested in environmental policy and local government. He is working with the Whatcom Watch as an intern. He is a California native living in Bellingham since 2012. He is currently enrolled at Western Washington University, where he is studying news editorial.