by Andrew Wise

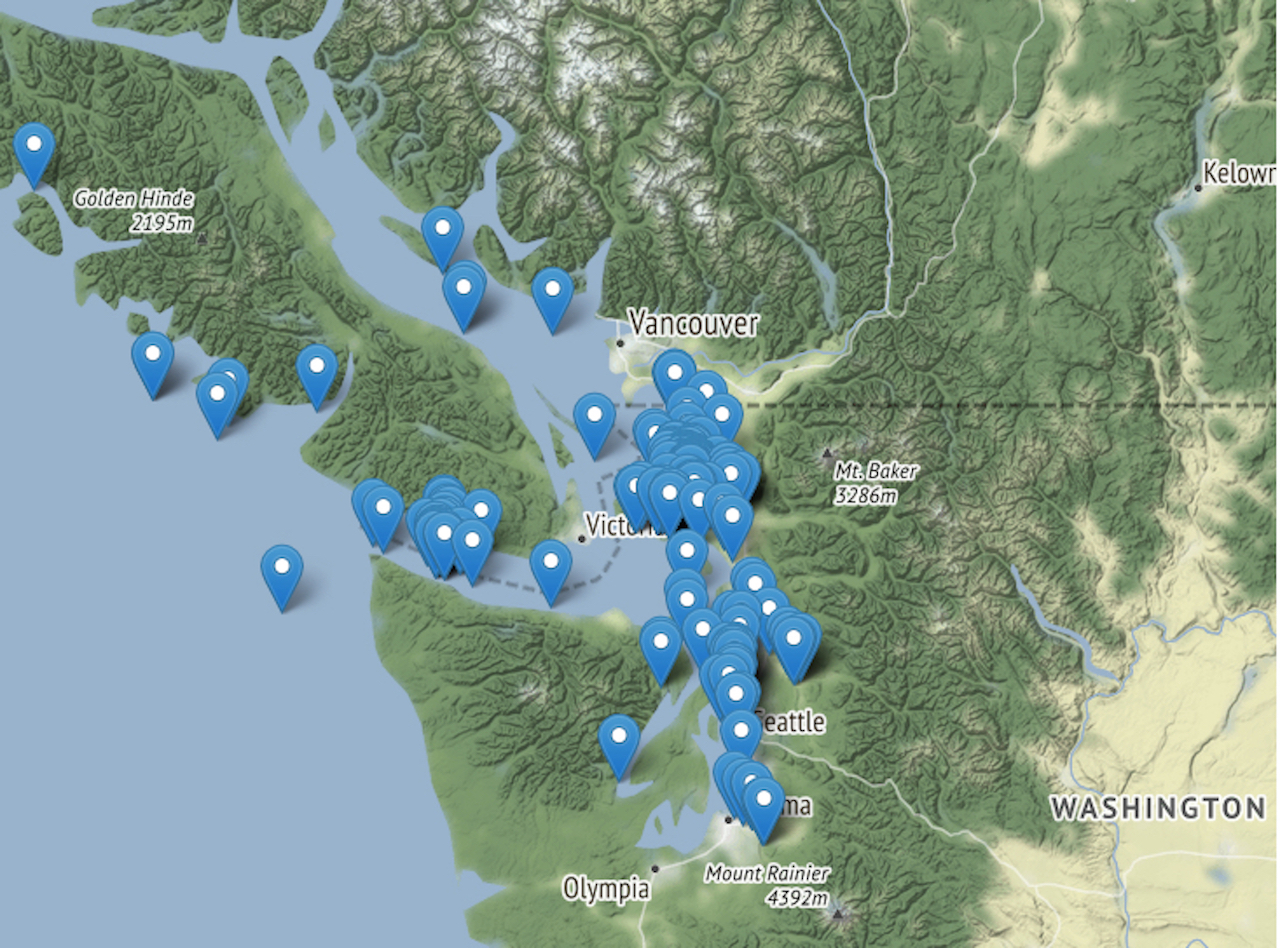

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife has maintained a map of locations where Atlantic salmon have been caught since the spill. Most are clustered near the release site, but some covered large distances.

Once a Prize, Now a Fugitive, State Agencies Weigh a Fish’s Future

It was 1978 when Andy Appleby first interacted with an Atlantic salmon in the waters of the Puget Sound. A young biologist fresh out of school, Appleby was in the first years of what would be a 30-plus year career with the Washington state Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). He found himself stationed near Purdy, Washington, part of a team tasked with evaluating the agency’s efforts to introduce a foreign species of salmon to Washington’s waters, one they hoped would establish itself within the ecosystem and become a popular sport fish.

“At the time, there was a single Atlantic salmon adult in a jar of formalin at Minter Creek hatchery,” Appleby said. “After years of releasing hundreds of thousands of smolts, that was the only one that had ever come back to the hatchery.”

Despite their ability to grow very large very quickly, Atlantic salmon proved poor colonizers. But when packed tightly together in submerged, netted enclosures, fed for one and a half to five years, they can be harvested as a lucrative aquatic cash crop.

Salmo salar is native to the cold waters of the north Atlantic. From Norway and Scotland to eastern Canada, it’s long been a seen as a prize sport fish for fly fisherman. A 109-lb. Atlantic was landed in Scotland in 1960.

As early as the 1950’s, WDFW was attempting to get the species to take root in the Northwest. Many liken the species to summer-run steelhead, but bigger. Those efforts ended in 1981, and just over a decade later the agency would shift to actively preventing those same fish from colonizing Washington rivers.

Appleby’s career paralleled the growth of the net pen salmon farming industry. Small mom and pop operations that started in the 1960s and ‘70s consolidated into large corporate operations. In 1985, the state legislature declared, “Aquaculture is agriculture,” and promoted the development of the industry. But when some of those operations had hundreds of thousands of fish escape their farms in the 1990’s, it was up to Appleby, among others, to assess the risk posed to the native salmon populations and help write new state regulations to prevent further releases from resulting in impacts to native fish populations.

Now retired from the agency, Appleby followed news coverage that threw the alien salmon back into the spotlight: on Aug. 19, 2017, an Atlantic salmon farm pen near Cypress Island containing more than 300,000 fish disintegrated under the weight of especially high tides. Aerial video from news helicopters flying on showed dark, slender figures slithering aimlessly in green water. The crumpled remains of the pens floating on the surface were sprinkled with the silvery sides of dead fish. Coverage of the incident quickly expanded to national and global news outlets.

Within just days, some salmon had made it to nearby rivers, stoking fears that a bad year for native salmon fishing in Washington waters would only get worse.

Appleby said he was frustrated with the coverage. His experience has led him to see the likelihood of Atlantic salmon colonizing the Northwest as minimal, and coverage advancing those concerns as “misguided.”

But the role Atlantic salmon plays in Washington is complex and uncertain. As state agencies and anglers continue to ply Whatcom County waters for the loose invaders, the future of the aquaculture industry in Washington hangs in the balance. A better understanding of its past, a history that extends over decades and has seen the WDFW both spawning and clubbing Atlantic salmon, may help inform the actions necessary in deciding its suddenly uncertain future.

As the last few remaining chunks of concrete and links of heavy chain were removed from the site of the Cypress Island facility more than a month after the collapse, anglers continued to catch Atlantic salmon and report their catches WDFW. Most reports are clustered around Cypress Island, but a few demonstrate the substantial range of these fish. Several have been caught along the western shore of Vancouver Island. On September 22, an Atlantic was reported on the Puyallup River south of Bonney Lake, approximately 16 miles inland.

Images from a youtube video using footage captured by First Nation members in British Columbia show injured and unhealthy salmon inside net pens.

Building a Salmon Farm

The pen that fell apart on August 19 is owned and operated by Cooke Aquaculture, a subsidiary of one of the largest fish farming conglomerates in the world. Cooke and its subsidiaries operate from Alaska to Scotland to Chile and Uruguay. And compared to many of those operations, even salmon farming in Canada, the amount of its fish penned in Puget Sound is relatively small.

As it stands now, the salmon industry in Washington is a tiny part of Cooke’s business. Cooke’s Washington facility accounts for less than two percent of the company’s $1.6 billion in annual sales. But the company has indicated plans to expand its operation in the Puget Sound region. The accident in August put a hitch in those plans.

In the wake of the incident, spokespeople for the company said that the Cypress island facility was due for an update and refit, including replacing the nets and metal structures that were ripped apart by an especially high tide.

Cooke was also preparing to update and expand another salmon farm located near Port Angeles, but that effort is now in doubt after Gov. Jay Inslee issued an order freezing the permitting process for all salmon farm projects in the state.

That moratorium, paired with the extensive coverage of the salmon escape, has opened a window for activists, tribes and city and county governments around the state to take a longer, more skeptical look at salmon farming. They find themselves at a crossroads. Cooke has only been involved in Washington since May of 2016, when it acquired Seattle-based Icicle Seafoods.

That acquisition marked the final step in a process that had started decades ago, as small, family-owned salmon farms in the Puget Sound were steadily consolidated into central ownership under Icicle. Now, the farms raising Atlantic salmon in Washington are outposts of a global, interconnected production system. At Donald Trump’s inauguration in January, the salmon on the menu came from a Cooke-operated net pen in Maine.

But in those other locations, operating at larger scales, significant environmental concerns have arisen. In Chile, some researchers see a connection between the onset of Red Tide, an algal bloom that can be deadly to marine organisms. In Scotland, massive infestations of sea lice have plagued net pen farms.

When it comes to assessing those risks in Washington, agencies at the federal and state level have been working for decades to identify the most significant dangers associated with this particular brand of aquaculture.

History Repeating

During three separate incidents between 1996 and 1999, nearly 600,000 Atlantic salmon escaped into Puget Sound, with escapees found as far north as Anchorage, Alaska. In the wake of those escapes, a team of Canadian researchers found Atlantic salmon that had managed to reproduce in streams on Vancouver Island. WDFW officials, including Andy Appleby, began assessing the likelihood of Atlantic salmon invading Washington rivers and displacing native fish in the region. They were also tasked with aiding the development of new state regulations related to net pen facilities.

But Appleby’s experience at the Minter Creek Hatchery decades earlier made him doubt the likelihood that Atlantic salmon would colonize rivers in the northwest.

A 1999 WDFW report authored by Appleby and Kevin Amos noted the earlier efforts by the department to try and establish Atlantic salmon runs, and the utter failure of that effort. It also shows that, to a large degree, the salmon caught upstream then had largely empty stomachs, indicating that they weren’t competing for food with wild salmon, or that they would sustain themselves long enough to reproduce.

This time around, WDFW scientists have seen similar indicators in the salmon captured. Agency spokesperson Michelle Dunlop said the contents of the stomachs of Atlantics have included some mussel shells and woodchips, but only one has indicated the consumption of forage fish.

Dunlop pointed to the 1999 study as the central piece of research to assuage concerns about Atlantic salmon colonization. A National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration Report from 2001 also concluded that colonization is a minimal risk associated with net pen salmon farming.

The NOAA report instead places feces and uneaten feed at the top of the list in terms of potential impacts from net pen farming. In that report, the agency looked at the risks of red tide, as well as the accumulation of heavy metals from feed and the impacts of pesticides and antibiotics from the farms reaching organisms living below.

The best defense against those impacts, the report states, is siting farms in a location that will flush those materials out of local waters consistently. Tides are effective in making that happen, but it means building farms like the Cypress Island operation in areas with strong tides puts them at greater risk of damage and increases the likelihood of fish escapes.

The leases for salmon farm sites are administered by the Department of Natural Resources. Tracking the condition of salmon farm sites falls under the jurisdiction of the Washington Department of Ecology, as does the permitting associated with establishing what materials the farms can release into the Sound. That includes things like pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and feces from fish.

Ecology requires an extensive array of monitoring reports from Atlantic salmon farms to track those pollutants, sea lice and dissolved oxygen, as well as spill prevention plans, all under rules set forth by the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System.

Meanwhile, it’s up to WDFW to try to control the quality of the fish itself, to track fish from their onshore rearing to their life in net pens, preventing the spread of disease and responding when an escape takes place.

This three-pronged agency effort was established in the WAC 220-76, which sets rules for aquaculture in Washington. It was originally passed in 1974 and significantly updated after the escapes in the late 1990’s.

In the process of developing the new regulations, Appleby said he worked closely with people from the salmon farming industry as directed by the legislation. The rules avoid prescribing specific details about the design and operation of net pens, like the number of anchors or size of the lines holding it in place, believing that as the farms have a strong financial incentive in preventing escapes they would implement the best technology available, and update facilities as that technology improved.

“The bottom line is, you can’t let your fish go,” Appleby said, and the way companies wanted achieve that standard largely remains up to them.

International Response

To the north, in British Columbia, Canadian fishery officials have been hunting for Atlantics escaped from Cypress as well, working closely with WDFW to try to capture as many of the fish as possible. According to Byron Andres, a biologist in the Canadian government’s Fisheries and Oceans office, 58 captures of Atlantic salmon have been made as of September 29 in B.C.

Six of those fish were found in the Fraser river. The Fraser is a massive river system that serves as a highway for spawning salmon. The river saw a record run of 30 million fish in 2010, but analysis of the yearly averages and returners per spawning fish have shown a steady decline in the last half-century, according to Fisheries and Oceans reports.

According to Andres, his office sees little risk of colonization and competition by Atlantic salmon in Canadian river systems, but still urges the removal of any Atlantics found in B.C. waters.

The agency is working to have as many of the fish delivered to their laboratories as possible for analysis. Andres is urging anglers to “retain the head and stomach if possible,” he said. “The whole fish is also fine.”

Many of the fish that have been delivered to the fisheries office remain in freezers waiting to be analyzed. Of the fish that they have opened up, Andres said only one fish’s gut contents indicated it had been feeding. But, he said it was worth noting that a vast majority of the fish had been caught with angling methods. The fish are jumping for hoochies, buds and other lures and flies.

Andres likened the Atlantic salmon currently wandering Puget Sound to cattle, a highly domesticated species selected over generations to maximize traits like converting feed into mass or remaining docile in close quarters.

“These salmon are many generations separated from wild fish,” Andres said. That separation significantly limits their ability to forage.

Despite having a farmed salmon industry about 10 times the size of Washington’s, B.C. hasn’t experienced releases on the scale of the Cypress Island spill. Farms in the province are strictly regulated. According to Andres, net pens must receive certification by an engineer that they can withstand strong storms and tides.

Andres said the event would likely propagate more fieldwork related to Atlantic salmon in the next few years, likely in the form of snorkel surveys in river systems where Atlantic salmon have been identified.

A Flashpoint for Activists

Despite the two-decade lull in Atlantic salmon releases, as well as research indicating that the risk to wild salmon populations posed by escaped farm fish is low, activist groups and tribal fishery associations on both sides of the border have continued to push for an end to net pen salmon farming in the region.

On September 9, members of the Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw and the Kwikwasutinuxw Haxwamis First Nations in B.C. boarded salmon farms operated by Marine Harvest, one of the largest operators in B.C., to protest the farms’ location in tribal fishing grounds.

These efforts come during what has been an especially weak year for salmon and herring fishing. Tribal members have used small video cameras on the ends of fishing lines to gather footage of disfigured salmon inside the farm pens. They have also documented large schools of herring gathering near the salmon pens, potentially impacting that fishery as well.

They’ve also documented diesel spills from mechanical equipment on net pen barges that created plumes of rainbow slick on the water.

A week later, on September 16, Washington-based activist groups in watercraft ranging from bright plastic kayaks to stainless steel research vessels took to the Sound near Bainbridge Island. They surrounded the Cooke salmon farming facility located just offshore, carrying signs calling for an end to net pens in the Sound, advocating efforts to preserve wild Pacific salmon.

Wild Fish Conservancy Northwest, an advocacy group focused on the preservation of native stocks of pacific salmon, orchestrated the protest. It came on the heels of the organization filing a 60-day notice of its intent to sue Island spill Cooke under the clean water act, claiming the company’s negligence led to the net failure and release. The notice making note of the fact that company officials initially attributed the failure, incorrectly, to high tides caused by August’s solar eclipse.

Patrick Myers, a communications specialist with the Wild Fish Conservancy, said the group had been planning the flotilla for two weeks before the escape at Cypress occurred.

“I don’t want to say it was fortuitous, because this is not something we wanted to happen,” Myers said, adding that after news reports of the spill, the organization saw a 30 to 40 percent jump in signatures for their online petition calling on Gov. Inslee to halt all salmon farming in the Puget Sound. That petition had garnered over 9,000 individual signatures and the support of 83 businesses as of September 29.

Myers said the organization is especially concerned about disease spread from farmed fish to native populations, as well as competition.

“These fish are going to be moving up rivers and competing for crucial habitat that is necessary for already endangered native species,” he said.

A Future for Salmon Farming?

On August 29, a Sierra Club-sponsored forum on the risks of salmon farming packed a meeting hall in Sequim. That came after Clallum County moved to postpone the permitting process for Cooke’s proposal to move and expand a farm off the nearby Ediz Hook, a 3-mile long sand spit that extends from the north shore of the Olympic Peninsula at Port Angeles. According to reports, Cooke asked county officials for time to focus on the response to the Cypress release before moving forward with the permitting process for the new facility.

As that response nears completion, and reports of Atlantic salmon from anglers slow to a trickle, state and county officials will be in a position to weigh the risks posed by this industry against its economic value. Cooke’s website points to the efficiency with which salmon convert their feed to edible food, double that of chicken and about 10 times better than cattle. Farmed fish has helped significantly in trying to meet a global appetite for salmon that has grown considerably in the last decade. More farmed fish would seem to reduce pressure to overfish native stocks.

But it’s accidents like the Cypress Island release that make that determination murky. The full effect of the fugitive fish roaming the Salish Sea will unfold over the next several years through fieldwork by biologists on both sides of the border. So far, the WDFW and Canadian Fisheries and Oceans have accounted for 200,000 of the 305,000 escaped fish. The rest are spread throughout these green waters, most apparently doomed to starve to death, a few still incidentally finding their way to a fisherman’s line or into a net.

As Andres put it, “It’s a big ocean out there.”

____________________________________

Andrew Wise is completing degrees in environmental policy and journalism at Western Washington University. A native of Colorado, reporting on northwest Washington is starting to make Whatcom County feel like home.