by Erin McConnell

Dr. Mauri Pelto stands at the 1984 terminus, or front, of the Sholes Glacier, which has since retreated by 590 ft. due to warming temperatures and decreasing snow accumulation. Photo from Mariama Dryak.

It’s a sunny August day, and all four members of the North Cascades Glacier Climate Project (NCGCP) research team are pretty beat. Today marks one full week into the field season, and the day-long backpacking treks and glacier traverses that characterize the majority of the 16-day expedition have made this rest day especially rewarding.

Having applied copious sunscreen, the group lounges by a babbling stream a few hundred meters from the toe of Sholes Glacier. Jill carefully paints the scenery in watercolor, Erin reads a collection of biographies on women in science, Mariama writes postcards to friends back home, and Mauri records the past week’s observations and measurements in his field notebook. At three-hour intervals, one of the group members straps on sandals and wades into the frigid stream to complete several horizontal depth profiles of the stream bed and measures flow velocity using biodegradable green dye.

Though less physically intensive, today’s measurements are nonetheless important: with these measurements, the team can quantify the amount of glacial runoff entering the North Fork Nooksack River — an important water resource for those living in the surrounding region.

The NCGCP is a long-term project designed to monitor the responses of glaciers in the North Cascades to climate change. Dr. Mauri Pelto, professor of environmental science and dean of academic affairs at Nichols College in Massachusetts, launched the project in 1984, and has since made annual treks to the North Cascades to measure changes in glacial mass, length, and runoff.

These measurements quantify the glaciers’ well-being: specifically, how likely they are to survive the changing climate, and how their contributions to streamflow in the Nooksack River Basin will change as they shrink. The city of Bellingham has provided financial assistance to the NCGCP in the past in order to gain insight into the future of its primary drinking water source, Lake Whatcom Reservoir, which is partially fed by North Cascades glaciers.

The Nooksack Tribe has also partnered with the program for five years to quantify changes in glacier runoff and resultant impacts on salmon resources.

Bad News for Glaciers

The December 2005 issue of Whatcom Watch published an article by Sarah Kuck predicting future glacier shrinkage as a result of projected climate change impacts. Since then, many of these impacts have become a reality in the state of Washington: air temperatures are warming, and the 2018 summer melt season saw temperatures nearly 2 degrees Fahrenheit above the 1948-2017 average. As a result, winter precipitation in the North Cascades increasingly falls as rain rather than snow.

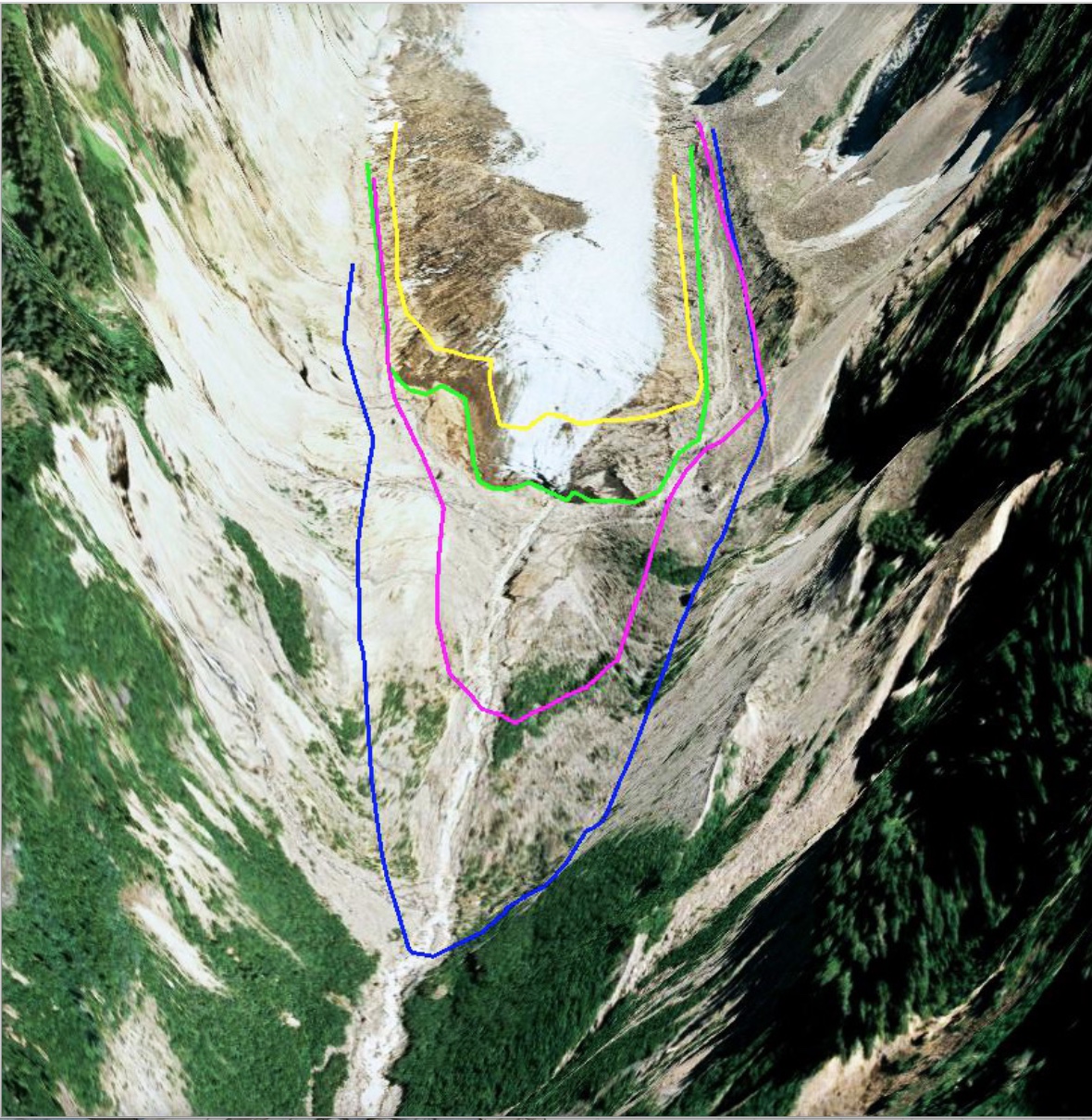

Retreat of the Deming Glacier, headwaters of the Middle Fork Nooksack River, since 1984. 1984 extent in blue, 1994 in magenta, 2006 in green, and 2011 in yellow. Image from Google Earth (2011), modified by Dr. Mauri Pelto.

These changes are bad news for the glaciers. Over the 35-year timespan of the NCGCP, annual mass balance, meaning the change in mass of a glacier over the course of a year due to gains from snow accumulation and losses from melt, has consistently been negative in all of the monitored glaciers. This is illustrated in the painting of glacier mass balance loss by Jill Pelto.

To quantify the effects of glacial mass loss on streamflow in the Nooksack Basin, the NCGCP focuses on the glaciers of Mt. Baker, a mountain known by the Nooksack Tribe as Komo Kulshan (“Great White Watcher”). Editor’s Note: please see the discussion on page 5 of our April issue regarding native names for Mt. Baker.

Runoff from two of Mt. Baker’s glaciers forms the headwaters of two Nooksack River branches. Sholes Glacier feeds the North Fork Nooksack River, which provides water to the town of Glacier. The Middle Fork Nooksack River, which runs into Lake Whatcom, originates as runoff from Deming Glacier. Local populations use water from these rivers for drinking and household use, hydropower, agriculture, and salmon harvesting.

All of the Mt. Baker glaciers have retreated significantly since 1984. The NCGCP monitors Rainbow, Sholes, Easton, and Deming Glaciers, which are now 10-20 percent shorter than they were before they began to retreat. Deming Glacier, stretching down the southwest side of Mt. Baker beneath the Black Buttes, has retreated by almost 2,625 feet (13 percent loss in length) since monitoring began. This means that it has shrunk by approximately 75 feet per year. The north-oriented Sholes Glacier has shortened by a similar portion, with 590 feet (12 percent) of retreat.

Glacier Size and Melt Rate

The contribution of glacial runoff to streamflow depends upon both the size of the glacier and its melt rate. When the melt rate increases due to warmer temperatures, streamflow initially increases as well, but when the glacier becomes too small, its runoff input declines.

The retreat of Sholes and Deming glaciers has altered the timing and magnitude of glacial runoff inputs to the North Fork and Middle Fork Nooksack Rivers. Since annual temperatures are on the rise, runoff has increased in winter, spring, and early summer, yet it has decreased in late summer — the driest part of the year when additional stream input is most needed.

Despite their mass loss, the glaciers are still vital in partially offsetting the reduction in streamflow that would otherwise result from exceptionally dry late summer conditions. The Sholes and Deming glaciers additionally provide an important mitigatory effect against warming stream temperatures.

In comparison with the North and Middle Fork Nooksack Rivers, the non-glacially fed South Fork has warmed three times as quickly in response to warming air temperatures. This, in concert with declining stream discharge, has stressed salmon populations in the South Fork, where the fish begin and end their life cycles.

The ability of the North Cascades glaciers to offset declining streamflow and warming stream temperatures is likely to disappear altogether by century’s end if no action is taken to curb accelerating climate change. “Sholes [Glacier] does not have a consistent accumulation zone and will not survive current climate,” says Dr. Pelto. “If action is taken, Deming [Glacier] has a chance. If action is not taken, neither [Sholes nor Deming] will survive.”

This makes water conservation especially necessary, especially for those who use Lake Whatcom as a primary water source. Fortunately, conservation efforts are already in action in the region. In 2003, the state of Washington passed the Municipal Water Law and Water Use Efficiency Program, which required all water service connections to be equipped with meters by 2017. This has since come to fruition for the most part (some rural water use is still not metered), and these meters provide financial incentives for residents and companies to reduce water use in daily life.

It is important to remember that lifestyle adjustments at the individual level can make a difference in slowing the factors that drive glacial retreat. Reducing personal water usage, as well as supporting lawmakers with stringent carbon emissions reduction policies, can assist in preserving the finite water resource of the North Cascades glaciers. This summer, the NCGCP will be back in the field observing these glaciers and monitoring their continuing responses to climate change.

‘Decline in Glacier Mass Balance,’ depicting the decrease in mass of North Cascades glaciers from 1984 to present. Painting by Jill Pelto, who specializes in science communication through art and has participated in the North Cascades Glacier Climate Project as a field assistant for 10 years.

___________________________________

Erin McConnell is a graduate student at the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute. For her master’s degree thesis project, she uses ice cores to study past climates. She was also a field assistant for the North Cascades Glacier Climate Project’s 2018 expedition.