by Meredith Moench and Rebecca Rettmer

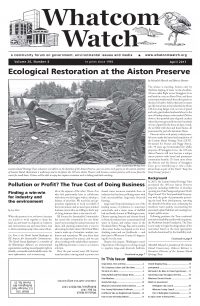

Lummi Island Heritage Trust volunteers sort debris on the shoreline of the Aiston Preserve, once an active rock quarry on the eastern shoreline of Lummi Island. Restoration is underway and in the future the 105 acre Aiston Preserve will become a nature preserve with access from the water for small boats. Visitors will be able to enjoy low impact recreation such as hiking and bird watching. photo: Lummi Island Heritage Trust

The silence is startling, broken only by rhythmic lapping of water on the shoreline. A heron takes flight across Smugglers Cove and lands in a tree on Abner Point, and three cormorants warily watch from their perch on the pier. It’s hard to believe that just four years ago this was a busy, noisy industrial site where 120-foot-long barges took on tons of gravel and rock, giant loaders lumbered about to the tune of backup alarms, rocks crashed 250 feet down to the sprawled arms of gravel crushers where they were ground down into hundreds of tons of gravel by the hour, six days a week, the air filled with dust and diesel fumes, all punctuated by periodic dynamite blasts.

Once an active rock quarry, today’s peaceful scene marks the latest land acquisition of the Lummi Island Heritage Trust (LIHT). Re-named for Homer and Peggy Aiston, who 70 years ago homesteaded the idyllic property off Smugglers Cove, the 105-acre Aiston Preserve will now become a unique nature preserve with broad and permanent community benefits. (To learn more about the Aistons and the history of Smugglers Cove, go to www.liht.org to view a video about them as part of the Trust’s “Keep the Story Going” project.)

Background

In 2015, the Lummi Island Heritage Trust purchased the 105-acre Aiston Preserve property, including 4,000 feet of shoreline opening into Hale Passage and greater North Puget Sound. The Trust purchased the property with the goals of permanently protecting the land from development, restoring the disturbed shoreline area, enhancing the nearshore water quality, reconnecting the associated upland habitats and creating low-impact public access.

Following purchase, the Trust conducted restoration feasibility studies with its partner, the Northwest Straits Foundation. The Trust is now ready to begin the design phase of the restoration based on the most appropriate methods determined by the feasibility studies. Located on the eastern face of Lummi Mountain, the site suffered severe damage to 500 feet of shoreline and 20 upland acres due to decades of mining and barging activities.

The Northwest Straits Foundation, established in 2002 as the non-profit partner of the Northwest Straits Commission, is focused on restoring and protecting the health of the northwest straits marine ecosystem. Supported by private and public funding, Northwest Straits Foundation has a strong history of successfully restoring nearshore habitat throughout the Northern Puget Sound region and currently manages several restoration projects in various stages of completion.

A key partner in the Aiston Preserve restoration project, the Northwest Straits Foundation works in partnership with the Northwest Straits Commission, County Marine Resources Committees, community volunteers, tribes, federal, state, and local agencies, businesses, universities, and non-profit organizations. Their mission is to create a vibrant marine ecosystem, now and for the future. Their website is www.nwstraitsfoundation.org.

Restoration vs. Reclamation

The Lummi Island Heritage Trust has adopted an ecological restoration approach, which will include:

• removing rock armoring, or “riprap” from the shoreline; over the years, layers of rock were added to parts of the shoreline to protect it from erosion and enable piers to be built for shipping rock products; removing the riprap will help restore the natural functions of tide and water and make the shoreline accessible;

• replacing native plants along the renovated shoreline and throughout the mined upland to allow the land to heal and to recreate the natural connection between the land and sea.

Typically, mining sites are “reclaimed” at the end of their useful life with the goals of stabilizing the terrain, assuring public safety, improving aesthetic appearance and returning the land to a useful purpose. One of the most famous examples of reclamation is Canada’s Butchart Gardens, located in Brentwood Bay, B.C. Now an elaborately landscaped wonderland of flowers, water features, and exotic trees, the former gravel pit is a popular tourist destination. As appealing as this may be, conversions such as this may not address the historic, ecological purposes of the land and may ignore considerations related to biotic integrity within a larger regional context. Ecological restoration is a much more complex, long-term undertaking beyond base-line reclamation requirements.

The Society for Ecological Restoration International defines ecological restoration as “an intentional activity that initiates or accelerates the recovery of an ecosystem with respect to its health, integrity and sustainability. Frequently, the ecosystem that requires restoration has been degraded, damaged, transformed or destroyed as the direct or indirect result of human activities.” Ideally, the restored ecosystem is self-sustaining and has the potential to persist indefinitely under existing environmental conditions, although those conditions may change or fluctuate as part of normal ecosystem development.

In the future when restoration efforts are complete, visitors will be able to enjoy spectacular views from the upland area of the 105 acre Aiston Preserve looking east toward Portage Island, Bellingham Bay, the Chuckanut Mountains and Mt. Baker. Photo: Ed Lowe

Restoration Groundwork

The Aiston Preserve project offers a unique opportunity for ecological restoration, and is especially relevant to on-going efforts to restore threatened Puget Sound salmon habitat. Revegetating the disturbed part of the Aiston Preserve’s upland will reconnect forested uplands with nearshore habitats, while removal of old shoreline armoring will help improve nearshore water quality impacted by mining activities. In preparation, feasibility studies have examined:

• Slope stability. The Trust is working with engineering geologists, mining consultants and the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Mining Division to identify and understand slope stability hazards on the mined areas. DNR will require the Trust to address slope stability issues, accumulated stockpiles of gravel and debris, and revegetation of the mined area as part of reclamation.

• Native plant surveys. The Trust has started to inventory native plants at the Aiston Preserve, starting with the especially sensitive bluff area known as Abner Point. Here volunteers are discovering tiny lichens, delicate dogtooth violets, fawn lilies, and stately madrone trees clinging to the rocky headland.

•Wildlife inventory. Anecdotal sightings of wildlife observed on the preserve are being noted and a more rigorous study will take place in the future.

The Restoration Plan

Ecological restoration is complex, requiring systematic planning with a monitored approach if ecosystem recovery is to be achieved for future health and integrity. Plans for restoration projects may include:

• a statement of the goals and objectives of the restoration project;

• a designation and description of the reference ecosystem;

• a clear rationale as to why restoration is needed;

• an ecological description of the site designated for restoration;

• an explanation of how the proposed restoration will integrate with the landscape and its flows of organisms and materials;

• explicit plans, schedules and budgets for site preparation, installation and post-installation activities, including a strategy for making prompt mid-course corrections;

• well-developed and explicitly stated performance standards, with monitoring protocols by which the project can be evaluated;

• strategies for long-term protection and maintenance of the restored ecosystem.

The Reference Ecosystem

Ecological restoration attempts to return an ecosystem to its historic trajectory, which is the focus of restoration design. Ecological, cultural and historical reference information must be gathered along with studies of comparable intact ecosystems.

Sources of such information include:

• ecological descriptions, species lists and maps of the project site prior to damage;

• historical and recent aerial and ground-level photographs;

• intact remnants of the site to be restored, indicating previous physical conditions and biota;

• ecological descriptions and species lists of similar intact ecosystems;

• historical accounts and oral histories by persons familiar with the project site prior to damage.

WWU Geophysics Students

One of the Trust’s goals is to locate the original shoreline, armored and long buried under dirt fill and rock by pier construction and mining activities. To find the buried shoreline, the Trust partnered with Dr. Jackie Caplan-Auerbach’s Western Washington University geophysics class. Along with Trust board member and geologist, Elizabeth Kilanowski, students began with the technique “seismic refraction” to look under the quarry floor. Lines are laid in a grid of wires. Geophones send a signal back to the computer when a sledgehammer pounds a heavy steel plate. The signal correlates to depth and density of the fill material.

Next, the students used Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) on the old quarry floor. GPR uses radar pulses to image the subsurface. Data was also provided by using a magnetometer which measures variations in magnetic minerals in rocks to evaluate what the subsurface might look like. Data from each method was analyzed back in the geology computer lab.

The Trust now has an estimate of where the original shoreline lies buried. Hopefully, some original pocket beaches will be uncovered, enhancing the restored shoreline’s biological functions.

Looking east toward Smugglers Cove and Abner Point, a cormorant is seen resting on one of two commercial piers located on the Aiston Preserve shoreline. The piers are remnants of the rock quarry active at this Lummi Island site prior to the Lummi Island Heritage Trust 2015 purchase of the 105 acre property. The Trust is currently working to restore the shoreline and uplands that were damaged by mining activities. Photo: Meredith Moench

Salmon Habitat

State and federal agencies, the Lummi Nation, and other tribes are all actively working to restore threatened salmon populations in Puget Sound. The salmon fishery is of great economic importance and a key species within the fabric of the Salish Sea ecosystem. Salmon are the primary food source for local resident Orca populations, whose numbers are severely dwindling, and their seasonal spawning in regional rivers contributes a food source and soil fertility upstream. They are also at the heart of the indigenous Coast Salish culture.

An essential aspect of Puget Sound recovery goals is habitat restoration. Restoration of the Aiston Preserve property and shoreline will significantly contribute to these efforts. The 4,000 feet of shoreline, pocket beaches, eelgrass and kelp beds will be restored for juvenile salmon feeding and seeking shelter. Forage fish such as Pacific herring and sand lance will inhabit the expanding kelp and eelgrass beds, and hopefully will reproduce in the restored nearshore habitat.

Since the end of mining operations at the quarry, a patch of bull kelp has expanded just offshore. This led to the question, was the kelp attached to the natural substrate or to the large boulders that are part of the shoreline armoring created by mining operations? Kelp serves as excellent habitat for fish and invertebrates. The Trust wanted to know if removing the armoring would negatively impact the kelp bed. In response, researchers recently spent several hours manipulating a remotely operated underwater vehicle (or ROV) to view and videotape the kelp bed. The ROV was lowered into the water and videos were made of the rocks and kelp. It was clear that the kelp was firmly attached to the large boulders. The videos also recorded eelgrass, Dungeness crab, pipefish, anemones, perch-like fish and even two sea stars. The videos will help the Trust decide how best to restore the shoreline at the Aiston Preserve while protecting the healthy kelp beds. To view the video go to http://www.liht.org/news-blog/underwater-in-smugglers-cove

The Trust is partnering with the Whatcom County Marine Resource Committee (MRC) to develop a pre- and post-restoration monitoring plan. The MRC will help develop and implement a monitoring plan. Monitoring activities will include both biological and physical elements such as forage fish spawning surveys, nearshore fish use (snorkel surveys), large woody debris accumulation, beach wrack composition, beach elevations, insect fallout and intertidal surface epifauna and algae. Volunteer citizen-scientists and professionals will help conduct the monitoring surveys.

Encouraging Natural Processes

Restoring natural processes begins with removal of the disturbance, in this case mining. Within months of the end of mining activities in 2013, small pioneering alders and other hardy plants began breaking through the hardpan dirt flats on the floor and benches of the mine. Cattails appeared in the retention pond and a lone Bufflehead shorebird was seen swimming there during a recent winter migrant visit.

However, always opportunistic, nature does not distinguish between native and non-native. Native plants are returning, but other aggressive invasive plants will also take hold if the site is not carefully monitored. Teams of volunteers have been trained to identify noxious invasive plants, like tansy ragwort. Identifying and pulling these weeds, volunteers have removed many garbage bags full in the effort to keep them from spreading further. The goal is to eliminate invasives as native species re-inhabit the site.

Human Activity and Restoration

In response to contemporary constraints, ecological restoration may accept and even encourage new culturally appropriate and sustainable practices. With thoughtful planning, cultural practices and ecological processes can be mutually reinforcing.

The Lummi Island Heritage Trust honors the human history of this place by calling it the Aiston Preserve. In 1906, the Japanese American Fish Fertilizer Company owned the property, processing the remains from the many thriving local fish canneries. Japanese men were smuggled in to work at the fertilizer company — hence the name Smugglers Cove. Since 1933, the property has been used on and off as a rock and gravel mine. In 1948, Homer and Peggy Aiston homesteaded the property with a small cabin on Abner Point. Peggy’s journals are a treasured record of Lummi Island’s early history. Kay and Lloyd Niedhamer later purchased the property and built a home there in 1968. Many recall Kay’s frequent swims across Smuggler’s Cove to Abner Point.

In the future, the Trust will create safe, low impact recreation opportunities such as walking, hiking, bird watching, and small boat access while assuring that the Aiston Preserve will never be developed and remain accessible to future generations. The Trust seeks a balanced approach to caring for the natural environment while allowing for education, scientific research and low-impact public use.

In keeping with these goals, public access will be limited to designated areas and human impacts will be monitored to minimize disturbance of habitat. Safe access areas will be created for hikers to enjoy the sweeping view looking east toward Portage Island, Bellingham Bay, the Chuckanuts and Mt. Baker. Small boats will have access to the restored shoreline.

Volunteers

Last year, more than 80 volunteers, including Washington Conservation Corps crews, put in almost 600 hours helping with invasive weed control and clearing out years of debris. Volunteers demolished a derelict storage building on Abner Point, loaded every scrap into skiffs and rowboats and transported the lot across the cove to the main shoreline. There, they filled dumpsters to the brim.

Funding

Ecological restoration requires a long-term commitment of resources, making long-term funding sources crucial. Even after ecosystem recovery has been achieved, there will still be the need for ecosystem management to counteract invasion of opportunist species, impacts of human activities, climate change and other unforeseeable events.

The Heritage Trust partnered with foundations, government agencies, businesses and more than 500 individuals to acquire the site and complete the Aiston Preserve Campaign. Grants are pending for the next phase of restoration design and permitting.

“The outpouring of support to purchase and protect this remarkable property has been amazing,” enthuses Rebecca Rettmer, Executive Director of the Lummi Island Heritage Trust. “Now our work begins to restore the damaged places along the shoreline and reclaim the mined area – all with an eye toward preserving this spectacular place for future generations of plants, wildlife and people.”

_______________________________________________________

Lummi Island Heritage Trust

The Lummi Island Heritage Trust is a 501c3 nonprofit organization and a nationally accredited land trust. Since its inception in 1998, the Heritage Trust has successfully protected 1,088 acres of land on Lummi Island. The trust owns and manages three nature preserves on the island, holds and monitors 15 conservation easements for private landowners, and offers outreach programs throughout the year to connect people to the natural environment. Their mission is to create a legacy of abundant open space, native habitat and natural resources on Lummi Island by inspiring people to protect and care for the island’s forests, fields, wetlands and shorelines, forever. For more information go to www.liht.org

___________________________________________________

Whatcom Watch Articles on the Lummi Island Quarry

Part 1. Lummi Island Quarry Owners Propose “Environmentally Friendly” Expansion — October/November 2011

Part 2. Do Citizens’ Concerns Matter? — December 2011

Part 3. Lummi Island: The Quarry is Served with Another Violation Notice — January 2012

Part 4. Lummi Island Quarry Is Illegally Diverting Water — February 2012

Part 5. Bumpy Road for Quarry Expansion — March 2012

Part 6. Barge Recovery Spills Oil at Lummi Island Quarry — May 2012

Part 7. Lummi Island Quarry Issued More Stop Work Orders — July 2012

Part 8. Lummi Island Quarry: County Fines Owner for Shoreline Violations — September 2012

Part 9. Guess Who Almost Came to Town — December 2012

Part 10. Lummi Island Quarry Is “Out of Control” — April 2013

Part 11. Aggregates West Goes Into Receivership to Avoid Bankruptcy — May 2013

Part 12. Lummi Island Quarry In Financial Collapse — August 2013

Part 13. What’s Happened to the Lummi Island Quarry? — August 2014

Part 14. Lummi Island Quarry Site to Be Protected — October/November 2015

Part 15. Kitchen Table Activism: From Hard Rock Mine to Nature Preserve — December 2015

_____________________________________

Meredith Moench is president of the Lummi Island Conservancy. Rebecca Rettmer is Executive Director of the Lummi Island Heritage Trust.