by Galen Herz and Rheanna Johnston

The Eleanor Apartments building is being constructed in the block bounded by North Forest, East Champion and Ellis streets. It will contain 80 one-bedroom apartments for low-income seniors. photo: Galen Herz

It is no secret that working people and families are struggling to find safe, affordable and quality homes in Bellingham. As young renters in the community, we wish to share our stories and perspectives on the shared housing challenge we face and add a new voice to this discussion.

More and more, our generation is realizing the “American Dream” of a spacious, detached home has its shortcomings. If our values increasingly prioritize sustainability and diversity, then we need to innovate and find new solutions to create denser, greener and more diverse neighborhoods.

Many of the conversations about housing leave out the voices of renters, despite renters making up 54 percent of Bellingham’s population.(1) We don’t claim to speak for all Bellingham’s renters and tenants, but we wish to share our stories to spark dialogue and advocate for creative solutions.

Renters are an integral part of what makes Bellingham the unique and thriving city we all love. We work, eat, play, vote and participate in the community with the same commitment as non-renters. Both us have been active in the environmental community organizing for clean energy. We were inspired by the Lummi Nation’s victory over North America’s largest proposed coal terminal and Bellingham’s support for their treaty rights. We are proud of our city’s defiance against the racism and bigotry of Donald Trump, for the thousands who participated in the historic Women’s March and WWU Blue Group’s powerful organizing for a Sanctuary City ordinance.

These victories give us hope that Bellingham can lead on sustainability and social justice; two issues that are deeply tied to the issue of housing. Unfortunately, the track Bellingham is currently on will lead us to be a playground for the super-wealthy. Our outdated housing policies reinforce existing class structures, force up housing costs and focus on single detached homes at the expense of denser, greener neighborhoods.

We envision a Bellingham with thriving medium-density, walkable and bikeable neighborhoods, with easy access to public transit, green space and good schools for everyone regardless of income or race. We are finding that our vision is also shared by many environmentalists, young professionals and families, social justice advocates, low-income seniors, students and teachers and neighborhood representatives. Ultimately, we believe a community that is good for the environment, as well as diverse and good for people of all backgrounds, is something worth fighting for.

Our Experience as Renters

We have both rented for four years in Bellingham and currently live in the wonderful York and Lettered Streets neighborhoods. Throughout the years we’ve experienced firsthand the small pool of available rentals. The vacancy rate in Bellingham is between 2-3 percent — the national average is at a much healthier 6.8 percent. Worse, many of these rentals are in bad shape – from moldy ceilings and graffitied basements to faulty electrical wiring and broken windows. We’ve seen it all.

One of us arrived at a new rental on move-in day, only to find that the bottom floor had been slowly flooding over the previous three months. The other once spent more than a month crashing with friends while searching for an affordable place that wasn’t moldy. Unfortunately, many renters eventually have no choice but to accept an unsafe housing situation, because they have no other option.

When one does find a livable rental unit, the application process is often no less challenging. Most landlords require a cosigner for the lease, hefty application fee, first and last month’s rent and a security deposit. The amount of money one is expected to pay upfront often prevents low-income folks from entering housing.

A further challenge is that most renters don’t know their rights. We often hear complaints that renters, particularly students, do not maintain their units or allow them to fall into disrepair. Most people would prefer to live in a clean, safe and nice home but it’s another matter if you cannot get your landlord to respond.

We argue that the best way to keep rentals, renters and neighborhoods safe is to increase tenant rights, education and access to resources. The Rental Safety Inspection Program is an excellent start to preventing landlords from taking advantage of renters, but we can and must do more to protect tenants, as outlined further below.

Bellingham’s Housing Challenge: Big Picture

Bellingham’s housing stock is becoming unaffordable for many of its residents.

Housing cost can risk an individual or family’s ability to pay for basic necessities like food, clothing, transportation and medical care. (2) A household is considered “cost burdened” when more than 30 percent of the monthly gross income goes towards housing costs. In Bellingham, 56.5 percent of renters fall into that category. (3) Worse, one in five Bellingham households was severely cost-burdened in 2015, spending more than half of their income on housing. (4) We see the impact of this in our schools — during the 2015-2016 school year 559 children qualified as homeless, a number which continues to rise every year. (5) We can and should do better.

Home prices have soared out of reach for working people. Between 2000 and 2015, median monthly rent in Bellingham increased 48 percent from $613 to $910, outpacing the 34 percent increase of median household income in the same period.(6) (7) From 2000 to 2015, the median home value doubled from $156,100 to $308,325. (8) (9) Last year, Bellingham home values soared 11.7 percent, with the median home value now conservatively estimated at $344,400 — a recent Bellingham Herald article reported the median price at $369,000 (10) .

Following the standard lender’s advice that “home price should not exceed 2.5 times annual income,” a household must make $137,600 annually to afford this median home. Fewer than 13 percent of Bellingham families make that type of money. (11) We’ve met new Western professors who can’t afford a home in Bellingham and must commute from Ferndale, driving up carbon emissions. We are becoming a city where only the wealthy can buy a home.

By virtue of income inequality being racialized, we are excluding minorities. For example, from 1983 and 2013, the average black household in America gained $18,000 in wealth, while the average white family gained $301,000. (12) Currently the average household wealth of a Latino/a household is $98,000, compared to $656,000 for whites. If you’ve ever taken a bus to Alderwood or Cordata, you’ll notice an increase in people of color — that’s a direct result of our zoning policies that have segregated our community by class and race. If our rents and home costs in Bellingham continue to skyrocket, our city will be unaffordable and decreasingly diverse.

Dan Bertolet, senior researcher at the Sightline Institute, referred to the housing challenge as cruel musical chairs: “The middle class competes for the cheapest places on the market, the poor end up on the streets.”

How Did We Get Here? Root Causes

We argue there are two interconnected root causes to our housing challenge. First, we have a speculative, deregulated and profit-driven housing market where housing is a commodity rather than a home. Second, outdated zoning laws have resulted in housing scarcity and segregated our community by class and race.

As with many problems our country faces, race and class are the underlying tectonic factors. We’ve had more than 80 years of federal, state and local housing policy that favors middle and upper-class whites and disadvantages the most marginalized in our country: low-income people, immigrants and people of color. (13)

Historically, these policies have been explicitly racist through redlining, discriminatory federal and private lending practices, and racially restrictive covenants in housing deeds formerly found in neighborhoods like Edgemoor. (14) Bellingham also has a long history of using violence against people of color to keep the city white: colonial violence against indigenous people, white mobs and leaders starving out Chinese families in 1885, driving out Sikhs in 1907 and the Japanese in 1942, and housing the state’s most active chapter of the KKK. In short, Bellingham did not become a ‘very white’ city by accident. (For more on this history, read “The Perilous History of White Supremacy in Bellingham/Whatcom County”). (15)

However, sometimes these policies are less explicit yet equally damaging; for example, anti-density zoning policies intended to preserve neighborhood character have instead resulted in a scarcity of housing and lack of diversity in our neighborhoods. Scarcity drives up property values and the cost of housing, affecting first-time homebuyers and renters. (16) Currently, zoning in Bellingham has segregated our community by class, and because income inequality is racialized, our community is also segregated by race. For example, York is only 13 percent people of color, compared to Birchwood which at 27 percent has twice as many people of color. (17)

Segregation can be seen in our elementary schools: 85 percent of Alderwood Elementary students (54 percent children of color) are receiving free/reduced lunch, compared to only 20 percent at Colombia (9 percent children of color). (18) Segregation by income and class not only divides our community, it also leads to worse housing and educational outcomes for the most vulnerable. (19)

Neighbors pictured above are part of Dudley Neighbors, a city housing land trust in Boston. photo: Cheryl Senter

Our Solutions

If renters and homeowners of all races and income can come together and engage in the political process, we can re-orient Bellingham and put it on a path towards affordability and well-being for everyone. We understand that it will take much more, but here are a few of the solutions we support:

Reduce speculation and profit-seeking in the housing market through prioritizing the development of community land trusts (CLTs) and other mission-driven housing options with increased funding and strong public-private partnerships. A study analyzing America’s largest CLT, Champlain Housing Trust in Vermont, found that managed properties become more affordable over time. (20)

Protect tenants by passing a “tenant bill of rights” similar to the policies advocated for by Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant. This bill includes policies that prevent income discrimination and excessive move-in fees, allow for move-in payment plans and cap tenant screening fees. Something as simple as requiring landlords to provide a copy of tenant rights could be very effective.

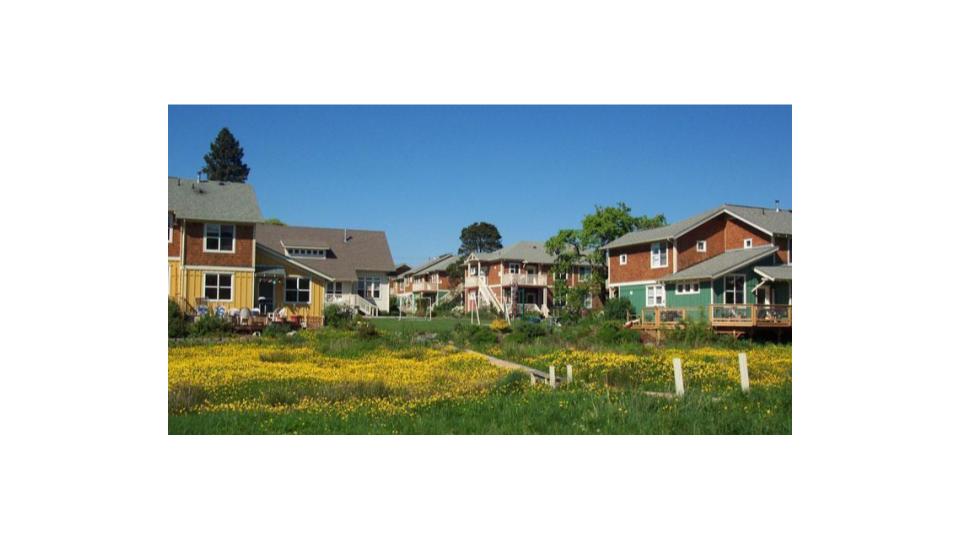

Bellingham Cohousing in Happy Valley features ‘Missing Middle’ housing options. photo: Bellingham Cohousing

Update our antiquated and restrictive zoning laws to allow for ‘Missing Middle’ housing in all neighborhoods, much like Buffalo, N.Y. (21) The ‘Missing Middle’ describes housing options in-between a detached home and high rise — a middle option. These options range from one attached unit to a nine-unit multiplex. Before the rise of the suburbs, American cities built rowhouses, townhouses, duplexes, and apartment-courts. The norm in many European countries are communities of dense, low rise, and aesthetically pleasing housing. Nelson’s Market in the York is an iconic community example of mixed use zoning where local businesses and homes come together (and they have great burritos for half-price after 2 p.m.!).

The ‘Missing Middle’ provides an option for students, young professionals and families, single people and seniors who don’t fit the lifestyle and/or economics of a detached home or high-rise. Homes that have an attached unit are far more energy efficient than detached units, making them better for the climate. (22) These in-demand housing options could curb rent and home ownership costs, provide walkable urban living and environmentally responsible growth.

Build enough affordable housing in a variety of types to provide options, especially in upper-income neighborhoods. Mixed-income neighborhoods will integrate our community and close the “rich” and “poor” divide, so that all Bellingham’s children have a chance at a good education.

More specific policies featuring model legislation will be released as part of the WWU Associated Students’ Local Lobby Day in mid-April.

Our generation is increasingly coming to recognize the limitations of the spacious, detached houses with big yards and white picket fences that used to be the American Dream. If we choose to value diversity, equity and sustainability then we must find new solutions. Ownership of detached homes is nothing to vilify, but when it comes to Bellingham’s future, we need to raise the stakes and work towards housing that is accessible, diverse and sustainable. If we do not adapt and innovate, the inclusive small-town feel of Bellingham will be shattered as the poor and middle class are shunted to other places.

Bellingham is an amazing city that we love because its residents are passionate, active and willing to fight for what they value. We hope you’ll join us in advocating for equitable and climate-friendly housing policy that will make homes accessible to Bellinghamsters of all kinds.

Endnotes

1. Selected Housing Characteristics, 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. 2015. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_15_5YR_DP04&prodType=table

2. Charette, Allison, Chris Herbert, Andrew Jakabovics, Ellen Tracy Marya, and Daniel McCue. “Projecting Trends in Severely Cost-Burdened Renters: 2015-2025.” Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. 2015. http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/jchs.harvard.edu/files/projecting_trends_in_severely_cost-burdened_renters_final.pdf

3. Selected Housing Characteristics, 2015 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. 2015. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_15_1YR_DP04&prodType=table

4. Bellingham Consolidated Plan 2013-2017. City of Bellingham Planning Department. 2012. https://www.cob.org/documents/planning/community-development/consolidated-plan/2017-full-plan.pdf

5. “Homeless Students in Washington State by School District.” Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. 2017. http://www.k12.wa.us/HomelessEd/Data.aspx

6. Bellingham Consolidated Plan 2013-2017. City of Bellingham Planning Department. 2012. https://www.cob.org/documents/planning/community-development/consolidated-plan/2017-full-plan.pdf

7. Ibid.

8. Profile Selected Housing Characteristics: 2000, Census 2000 Summary File 3. U.S. Census Bureau. 2000. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_00_SF3_DP4&prodType=table

9. Bellingham Home Prices and Values. Zillow Housing Database. 2016. http://www.zillow.com/bellingham-wa/home-values/

10. http://www.bellinghamherald.com/news/local/article105975817.html

11. Selected Economic Characteristics, 2015 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. 2015. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_15_1YR_DP03&prodType=table

12. Asante-Muhammed, Dedrick. “The Ever-Growing Gap.” Institute for Policy Studies and the Corporation for Enterprise Development. 2016. http://www.ips-dc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/The-Ever-Growing-Gap-CFED_IPS-Final-1.pdf

13. Rothstein, Richard. “The racial achievement gap, segregated schools, and segregated neighborhoods: A constitutional insult.” Race and Social Problems, 7(1), 21-30. (2015).

14. “Lot 1, Block 1, Edgemoor, addition to the City of Bellingham, Division 3.” Larrabee Real Estate Company. 1948. goo.gl/v0rvjg

15. “The Perilous History of White Supremacy in Bellingham/Whatcom County.” Perilous Press History Project. 2015. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B-RSIXZhAaj1dFJIRW93Z3hwQjA/view

16. Andrew Price. “Housing unaffordability is the result of artificial scarcity.” Strong Towns. 2016 https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2016/4/20/affordable-housing

17. “Race and Ethnicity.” Statistics Atlas. 2017. http://statisticalatlas.com/neighborhood/Washington/Bellingham/York/Race-and-Ethnicity

18. “The Opportunity Gap.” ProPublica. 2016. http://projects.propublica.org/schools/

19. Rothstein, Richard. “School Policy Is Housing Policy: Deconcentrating Disadvantage to Address the Achievement Gap.” Race, Equity, and Education, pp.27-43. 2016. http://www.springer.com/cda/content/document/cda_downloaddocument/9783319237718-c2.pdf

20. Stokes, John. “Lands in Trust; Homes that Last” Champlain Housing Trust. 2009. http://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/report-davis-stokes.pdf Each school listed was individually searched

21. Sommer, Mark. “Buffalo’s zoning code steps into 21st century.” Buffalo News. 2016. http://buffalonews.com/2016/12/27/city-code-21st-century/

22. Location Efficiency and Housing Type. Environmental Protection Agency. 2014. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-03/documents/location_efficiency_btu.pdf

___________________________________

Galen Herz is a biochemistry and anthropology double major at WWU, while Rheanna Johnston recently graduated from WWU with a degree in environmental policy. Along with Ben Larson, they recently founded the Bellingham Tenants Union, and are active organizers in the community. You can reach them at bhamtenantsunion@gmail.com or check out the Bellingham Tenant’s Union on Facebook.

The Eleanor Apartments building is being constructed in the block bounded by North Forest, East Champion and Ellis streets. It will contain 80 one-bedroom apartments for low-income seniors. See the article on page 12.