by Meghan Fenwick

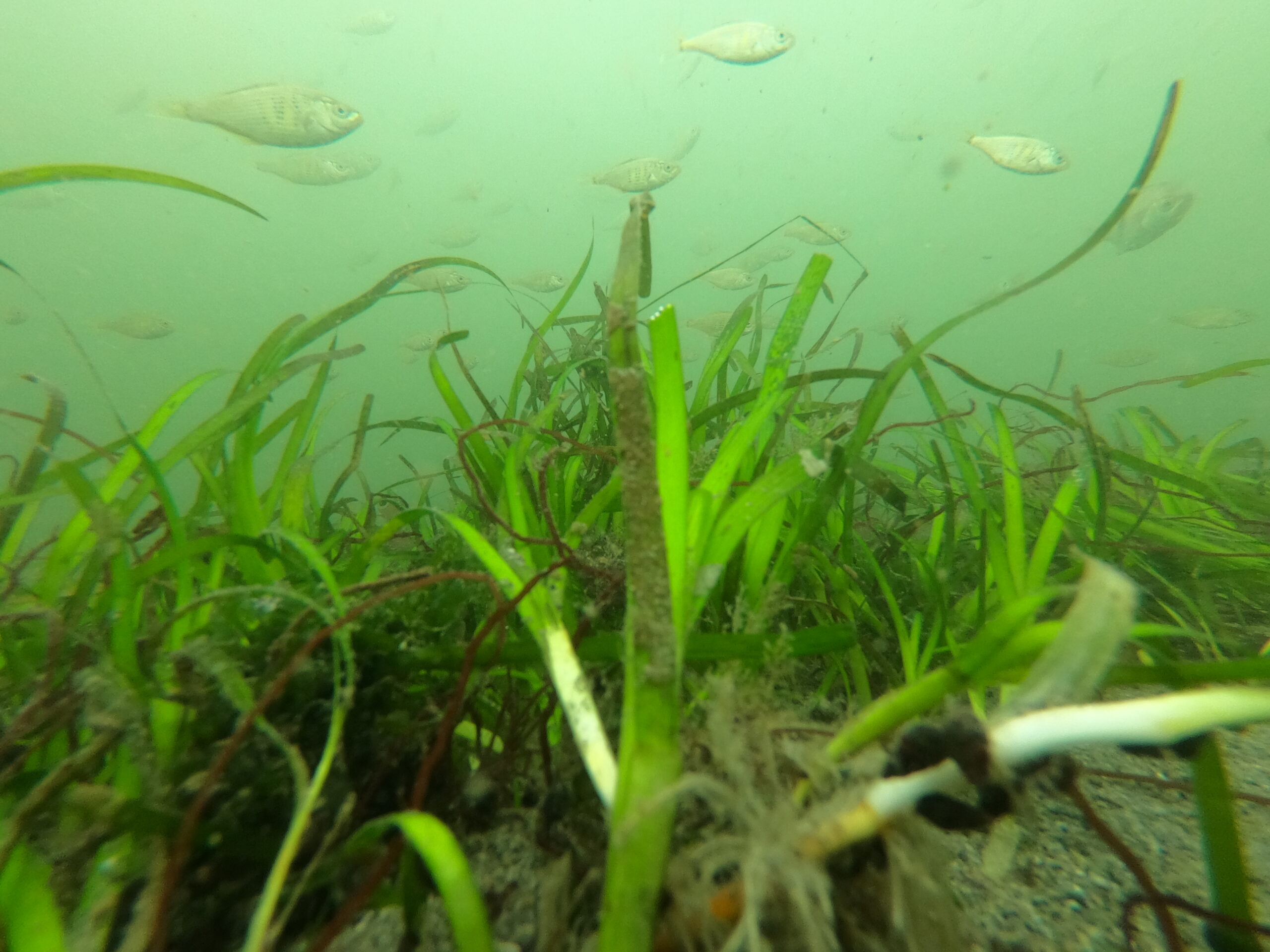

Shiner perch swim through a bed of eelgrass in Joemma Beach State Park, Wash.

courtesy photo: DNR’s Nearshore Habitat Program

This summer, The Friends of the San Juans, the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Cornell, and the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Labs teamed up to study the declining eelgrass population in the San Juan Islands.

The underwater eelgrass meadows that hug the San Juan shorelines provide protection for a long list of marine life to forage, including juvenile salmon, herring and the great blue heron. They also help stabilize the sea floor and sequester carbon, valuable assets to a shoreline community facing increasing coastal erosion and storm events due to climate change.

“I think seagrasses are often undervalued,” said Olivia Graham, a postdoctoral researcher at Friday Harbor Labs. “A lot of people think about rainforests or coral reefs, but seagrasses are also really dynamic biodiverse habitats that help fight climate change.”

While statewide eelgrass meadows have remained stable since the turn of the century, meadows in the San Juan’s more than 400 miles of coastline have seen significant decline.

Here, eelgrass grows in intertidal and subtidal zones, in contrast to most East Coast meadows which prefer deeper water. Intertidal zones experience high and low tides, while subtidal zones are always submerged. The visibility of intertidal meadows at low tide has allowed the local community to observe this trend over time.

“We used to rent out to the north end of [San Juan] Island near the Westcott Bay area, and it was loaded with eelgrass, just clouded,” said Kari Koski, a longtime resident and volunteer for the project. “I’ve seen a huge, huge change, all over the islands in both the eelgrass and the kelp.”

Eelgrass is threatened by physical disturbances, low-water quality, warmer temperatures and less-light availability, factors which can amplify each other and damage the short- and long-term health of a meadow. The combination of these stressors makes it difficult to determine why one bed fares better than another in a similar environment. By analyzing the depth, distribution, and disease prevalence of the eelgrass over time, ecologists can begin to narrow it down.

Wasting Disease

Another main suspect of these declines is a pathogen called Labyrinthula zosterae, or eelgrass wasting disease. When a blade is infected by the pathogen, black lesions spread outward from the middle. Unlike the blurry outlines of a sunspot or a scour mark, the mark of wasting disease leaves crisp margins between live and dead cells.

Since the first major outbreak on the East Coast of the United States in the 1930s, questions still remain about what causes the pathogen to spread, and what can be done to protect against it.

Studies have shown that declines are coinciding with marine heat-wave events, and lab experiments have shown that the pathogen fares better in warmer conditions. In a 2021 study (1), Graham reported that 95 percent of the eelgrass blades in the San Juan Island’s 4th of July Beach meadows were infected. The results also showed that the presence of the pathogen can slow growth rates.

“We’re seeing that these high disease levels are associated with declines at some of our meadows,” Graham said. “One of our sites, Beach Haven on Orcas Island, disappeared completely in the intertidal.”

In contrast, the subtidal eelgrass still stands, leaving Graham to wonder if the deeper meadow serves as a refuge against the list of climate stressors. Comparing the two meadows in terms of depth, distribution, light availability, temperature and salinity can help identify the ideal eelgrass habitat.

Research Methods

While today’s eelgrass beds can help tell the story, another tactic is to observe how a population has changed over time. In 2003, the same team of organizations completed the first comprehensive survey (2) of all the San Juan County eelgrass, creating the baseline for this study two decades later.

“The disease data, coupled with the distribution and depth trend data, will help us start putting these pieces together,” said Tina Whitman, science director of The Friends of the San Juans. “We have some of the more significant declines, so the hope is to start to figure out what’s going on here to help inform eelgrass conservation efforts.”

The project kicked off in June when scientists and volunteers formed a snorkeling team and dove to 11 meadows at seven of the San Juan County Islands. They carefully plucked single blades, coiled them tightly and placed them in mesh bags to be sent to the lab. Strapped in weighted belts, the snorkelers moved in a line parallel to the deepest edge of the meadow, collecting a random sample to be tested for wasting disease the same day.

Meanwhile, researchers will steer a ship with an underwater video camera in tow, charting the distribution of the eelgrass meadows at 20 sites near the islands. Every second that an eelgrass plant appears in the footage is a data point, and, from this data, a boundary can be drawn for where the eelgrass begins and ends.

“Research tends to be at the shallow-water edge, and tends to be not that many sites because we have to analyze the plants for disease the same day,” Whitman said. “But with the inclusion of more staff from our partnership, we are able to expand the sites.”

Some of the sites were chosen based on previous surveys from DNR’s Nearshore Habitat Program, which has been surveying Puget Sound eelgrass since 2000. By overlapping survey sites, the team is able to identify areas where eelgrass is increasing or decreasing. Other factors included accessibility and critical habitat for herring and other species. Friday Harbor Labs has monitored disease at several sites for the past decade.

The 2003 survey showed short-term population decline, with severe losses in Westcott and Garrison Bay on San Juan Island, while DNR’s consistent monitoring points to long-term declines. This data is centralized at DNR’s Puget Sound Eelgrass Monitoring Data Viewer (3), a map of Puget Sound that flags hundreds of eelgrass beds and lists available trend data. The goal is to publish the results from this project to this dashboard by 2025.

The study’s baseline hypothesis is that there has been no change. “But there’s probably going to be some changes,” said Jeffrey Gaeckle, seagrass ecologist at DNR. “It may happen in some localized areas and not comprehensively across the San Juan Islands, and then we can identify stressors nearby.”

Boating

Eelgrass is especially sensitive to light, which can be compromised by lower quality and clarity of the water. Excess nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, can be introduced through sediment runoff, increasing the growth of algae that competes with eelgrass for light.

Another wedge between the sun and the eelgrass is the most direct human impact: boats. The San Juan Islands are a popular boating destination for area residents and tourists. Not only can shading a meadow for a prolonged period damage the eelgrass, but anchors, chains, motors and even kayak paddles can rip out the eelgrass by its roots. The snorkeling team carefully avoided these roots, because without them the blades have no chance to grow back.

“It’s a tough balance,” Gaeckle said. “People typically want to have their boats closer to shore to access it more easily, and so it’s not as exposed to currents or waves. But we want them offshore because we don’t want them to be damaging the critical habitat.”

Public docks and mooring buoys can help alleviate the pressure on eelgrass beds while providing boaters a place to tie up. San Juan County is working to remove and upgrade outdated docks and piers. The 2020 San Juan County Public Mooring Buoy Project (4) seeks to add 41 mooring buoys at eight sites across the islands during phase one.

Many government and nonprofit organizations have joined in the effort to revamp the boating infrastructure. In 2020, the Friends of the San Juans received grant funding from the Washington State Salmon Recovery Funding Board and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for a mooring buoy upgrade program. This program provided technical and financial assistance to private and public property owners interested in evaluating and replacing outdated mooring buoys.This process requires permits from multiple state agencies and funding.

“We know that eelgrass is stressed, and we know that there’s a whole host of stressors,” Whitman said. “Some things are easier to control than others. We’re not gonna change the ocean temperature, but we can change our own behavior.”

Koski has a stake in both sides of the issue. She served as director of the Whale Museum’s Soundwatch Boater Education Program in 1993 for 18 years, and describes herself as a “kelp-o-phile.”

While she is still looking to help where she can, such as volunteering for community science projects, as a boater herself, she admits that these guidelines can be difficult to navigate.

“I think you have to actively seek this information out,” Koski said. “I know a lot of people are doing a lot of promotional things, but I think unless you have it on your radar, you’re probably not going to see it.”

Conservation and Restoration

The Friends of the San Juans “Green Boating” (5) page has educational resources to help boaters leave no trace. The website explains how to share the waters with eelgrass, whales and other marine life. It includes a downloadable map that outlines shallow and deepwater eelgrass and herring habitat to avoid anchoring in.

“We love these places and I think we’re all a little bit worried that we’re loving them to death,” Koski said. “I don’t know if we’re doing that, but we certainly are putting a lot of pressure on these environments that are the reason why we live here or visit here.”

Graham recalls one instance during her field work on Lopez Island where a waterfront property owner told her that he waters the eelgrass during extreme low tide. While an impractical strategy on a broader scale, this effort does have scientific basis: studies have shown that eelgrass prefers lower temperature and salinity.

As scientists and activists work to determine the cause of decline while conserving healthy meadows, restoration efforts are also being explored through DNR’s Nearshore Habitat Program. Since 2012, DNR has been transplanting eelgrass blades to Puget Sound sites where eelgrass has historically grown.

After assessing eligible donor and transplant meadows, the DNR team harvests eelgrass shoots, ties them to rebar and places them on the bed floor. The sites are then monitored for up to six years. In Joemma Beach State Park, north of Olympia on Key Peninsula, eelgrass populations are thriving since transplanting 120,000 shoots in 2013. Today, that number has surpassed one million.

“It’s not always successful,” Gaeckle said. “But in places where we’ve had success, we’ve seen a great rebound of seagrasses in that area, and it’s encouraging.”

In 2013 and 2017, more than 3,000 shoots were planted in five sites at Westcott Bay. All of the eelgrass was absent from two of those sites within two years, and none of the populations showed signs of growing.

About 50 percent of DNR’s large-scale restoration efforts have been successful. Many variables inhibit transplant success, such as strong wave currents or interference from marine animals. At Quartermaster Harbor in Vashon Island, the crabs were so desperate for habitat, they overworked the eelgrass before it could substantially grow, said Gaeckle.

One of the challenges of studying eelgrass in the San Juans is that there is a convergence of multiple waterways, including flows from the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Strait of Georgia, the Fraser River, other rivers and the exchange from south Puget Sound. Most of the successful transplants have occurred in the south.

“They’re pretty tough plants,” Graham said. “When you add in these multiple stressors of water quality degradation from humans with heat stressors and the pathogen, things get pretty dicey. But generally speaking, these are pretty resilient plants.”

After the wasting disease pandemic of the early 1930s, eelgrass was considered absent from the coast of Virginia for almost 70 years. Rapid development also contributed to habitat degradation, seemingly sealing the eelgrass fate.

Then, in the late 1990s, a combined effort by volunteers and academics to scatter 70 million seeds resulted in a rebound of more than 7,000 acres of eelgrass meadows. Though conditions may favor East Coast eelgrass, success stories near and far contribute to our greater knowledge of restoration possibilities.

“Eelgrass is so confusing, and we’re not sure exactly all the things that are causing the problems,” said Koski. “But we have some good ideas, and we’ve got so much going on here for such a small community. We have a lot of ways to get involved with stewardship and opportunities to learn from people who are doing the right things.”

How to Protect the Eelgrass

The Friends of the San Juans is an environmental advocacy nonprofit organization. The group was formed in 1979 by a grassroots movement to protect and conserve the islands in the face of rapid development. Their first priority was to aid the county in establishing a comprehensive land use plan. Today, they are focused on education, research and policy work geared toward climate action and ecosystem health.

How to help the eelgrass population, according to The Friends:

• Anchor out of eelgrass beds. Use a public marina or mooring buoy when available, and anchor deeper than 15 feet at low tide.

• Print out the downloadable map (1) of eelgrass and herring habitat in the San Juan Islands and keep a copy on your vessel.

• Consider updating your dock with light-penetrable wood.

• Report derelict fishing gear that may be endangering wildlife or wildlife habitat to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife online (2) or by calling 855-542-3935.

• Make sure your vessel is in good condition before setting sail to avoid potential spills. In the event of an oil or fuel spill, stay on the scene and immediately contact the Washington Emergency Management Division at 1-800-258-5990.

• If you want to investigate eelgrass, try looking at drifts that have already broken from the bed.

• Continue to learn more and spread awareness. Sign up for The Friends’ newsletter (3) for updates and events, and visit the “Green Boating” page (4) for more information.

The Friends of the San Juans References

1. https://sanjuans.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/FSJ_AnchorOutMap_Newley.pdf

2. http://www.derelictgeardb.org/reportgear.aspx

3. https://sanjuans.org/contact/sign-up-for-a-newsletter/

4. https://sanjuans.org/program/green-boating/

___________________________

References

1. https://par.nsf.gov/servlets/purl/10373338

2. http://sanjuans.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Eelgrass-Final-Report.compressed.pdf

4. https://www.sanjuanco.com/DocumentCenter/View/21002/2020-San-Juan-County-Public-Mooring-Buoy-Project

5. https://sanjuans.org/program/green-boating/

__________________________

Meghan Fenwick is a senior in her last quarter at Western Washington University. She is majoring in environmental journalism and loves exploring the connections between people and the natural world.