Editor’s Note: The following is an executive summary of the State of the Salish Sea, which was produced by the Salish Sea Institute at Western Washington University. The full report, released at the end of May 2021, details the work of more than 20 authors and contributors. It is the first comprehensive overview of the vast estuary and ecosystem since 1994. To download a copy of the full report or purchase a 275-page print copy, go to https://wp.wwu.edu/salishsea/. Dr. Kathryn L. Sobocinski, its lead author, is WWU Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies. Next month, Whatcom Watch will publish a profile of Ginny Broadhurst, director of the Salish Sea Institute, conducted by our Whatcom Profiles columnist Ken Brusic.

by Kathryn L. Sobocinski

First of two parts

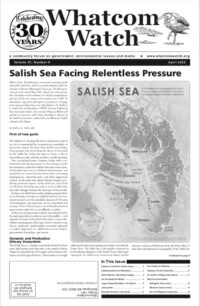

The Salish Sea is a biologically diverse inland international sea that is surrounded by mountainous watersheds of spectacular beauty. For more than 10,000 years, Indigenous peoples have lived along the shores of and cared for the Salish Sea. Today, the region is home to almost nine million people, and that number is rapidly growing.

Our expanding human footprint brings with it urbanization and ensuing impacts on the seascape as ports become busier, underwater habitats become noisier, natural shorelines give way to hardened infrastructure, and watersheds are converted from native forests to housing developments, industrial parks, and other impervious surfaces. At the same time, global climate change is producing profound impacts on the Salish Sea, as sea level rise threatens low lying areas and as ocean acidification and other changes threaten the intricacies of marine life.

In short, the Salish Sea is under relentless pressure from an accelerating convergence of global and local environmental stressors and the cumulative impacts of 150 years of development and alteration of our watersheds and seascape. Some of these impacts are well understood but many remain unknown or are difficult to predict.

In the years and generations ahead, restoring the Salish Sea and supporting its resilience are both possible — and urgently necessary. As detailed in this report, many stakeholders and programs offer hope in how to lead the way, but an integrated, transboundary ecosystem approach is needed, supported by collaboration across borders, governments, disciplines, and sectors.

Dynamic and Productive Estuary Ecosystem

The Salish Sea is a complex waterbody defined by fresh water and marine water that mix in two primary basins (Puget Sound and Strait of Georgia) and numerous subbasins carved by glacial history. These basins are strongly influenced by their surrounding watersheds, especially the Fraser River. The Salish Sea is also tightly connected to the biophysical dynamics of the Pacific Ocean. Freshwater input gives the Salish Sea its status as an estuary and the immense volume of freshwater from the Fraser River is what drives the physical oceanography of the Salish Sea. Briefly stated, as the relatively warmer, less dense fresh water flows out from the Fraser River onto the surface layers of the Salish Sea, the colder and relatively dense salt water from the Pacific Ocean is drawn in, creating an oceanographic process known as exchange flow. This large-scale exchange flow in turn drives the fundam¥ental circulation in the Salish Sea.

Similar in function to the circulatory system within our own human bodies, understanding how water within the Salish Sea circulates is important because it distributes the nutrients, oxygen, and other essentials that fuel primary productivity and a very diverse food web. That natural fuel and productivity sustain numerous inter-connected habitats, like eelgrass beds, kelp forests, and sponge and oyster reefs, each of which are described in this report. Those biogenic habitats in turn provide structure and shelter for multitudes of other organisms, including many of importance to humans. Meanwhile, circulation mitigates local impacts of some human harms, such as contaminants, eutrophication, and low dissolved oxygen by continually moving water throughout the system. As climate change disrupts this strong, longstanding, and predictable circulation by altering, for example, the timing and volume of freshwater inputs, the ramifications to the Salish Sea estuarine ecosystem are potentially significant.

Local Urbanization and Climate Change Converge

Human impacts are multifaceted and extensive within the Salish Sea. Population growth drives urbanization and development, which in turn triggers structural changes to the landscape and seascape like habitat fragmentation, shoreline armoring, conversion of vegetated areas to impervious surfaces, and profound changes in watershed and wetland hydrology. These gradual but damaging trends also increase nutrient and contaminant loading to the estuarine waters and limit the scope and scale of local fisheries.

While the causes of climate change are global and primarily from greenhouse gas emissions, impacts of climate change manifest locally and are already becoming physically and biologically evident in the Salish Sea. As described in this report, that evidence includes documented, measurable warming of the atmosphere and oceans, changes in global and regional precipitation patterns, and rising mean sea level — all effects contributing to known changes within the Salish Sea ecosystem. Increased seawater temperatures and ocean acidification are currently stressing biota, and accelerating rates of both point to potentially significant ecosystem changes ahead.

Fortunately, scientists and managers continue to compile data and analyze trends that collectively help us better understand some of the predicted near-term effects of global climate change, aided by global- and regional-scale models. Regional accuracy of such models and their predictions is improving, but our understanding of how Salish Sea organisms, ecosystem processes, and interactions are affected by global climate change is less certain, especially looking ahead into the future. When the effects of global change in our oceans are combined with the increasing disruption from local urbanization, the Salish Sea estuarine ecosystem will continue to degrade. Forecasting and planning related to these changes is a challenge for the coming decades.

Cumulative Effects Impair Systems and Species

Salmon and orcas are emblematic of the beauty of the Salish Sea, and, along with numerous lesser-known species, signal to us that cumulative troubles are mounting in our ecosystem over time and space. Theory and observation suggest an eventual tipping point, and scientists and managers are rushing to understand if and how the Salish Sea has the capacity to recover from short-term disruptions alongside ongoing chronic stress. Much more work is needed to unravel the repercussions of cumulative and relentless stress on the Salish Sea ecosystem, including its resident salmon, orcas, and hundreds of other aquatic species.

Orcas provide a case study for how one species is faring under the cumulative effects of human activities. The Southern Resident population — salmon-eating orcas found in the Salish Sea in the summer months — are challenged by at least three main threats: scarce food, contaminants, and marine noise. Chinook salmon are their primary food source and also the species most in decline throughout the region. Contaminants in the fish they eat are taken up and stored in their bodies, impeding their ability to reproduce and fight disease. Orcas are also increasingly forced to hunt in a fog of noise, which can affect their ability to capture the food they need to successfully reproduce. As a top predator, orcas rely on a functional ecosystem — at all levels — for survival, but face an increasingly inhospitable habitat.

Ecosystem Decline Outpaces Restoration

Structural changes are needed to be truly effective in supporting a thriving ecosystem.

Over time, government agencies and others around the Salish Sea have implemented numerous management programs, policies, and regulations to protect the ecosystem. Transboundary governance agreements have been signed and initiatives launched. Yet, as the 2010 Coast Salish Gathering Treatise asks, “Would the Salish Sea be in the state [it’s] in if, in fact, these agreements were doing what they intended to do?” Indeed, layers of laws, treaties, regulations, and jurisdictions make for a complicated and even fragmented approach to Salish Sea governance, exacerbating challenges from global climate change to local lack of enforcement and funding. The cost of business as usual is high, especially as we anticipate further declines and unknown repercussions for the region.

Righting the course to a more functional and sustainable Salish Sea requires a strong scientific foundation. It also requires a renewed and clear commitment to strategic planning, systemic changes in governance, large-scale investment, and significant shifts in our economic systems, collective values, and changing relationships to our lands and waters. Now is the time to shift thought and policy paradigms from treating the environment as a resource to instead build systems of relationships and responsiveness that are based in science and incorporate the interconnected system of humans and environments. As illustrated by several encouraging examples in this report from all around the region, we know that much can be achieved through well-coordinated restoration, mitigation, and protection measures.

Looking ahead, there is hope through more action and ecosystem-scale collaboration.

Not since The Shared Waters Report in 1994 has there been a holistic assessment of the Salish Sea as an integrated ecosystem. More than 25 years later, a fresh snapshot is timely — and necessary. The regional population has grown by over two million people since the publication of The Shared Waters Report, and new threats are recognized in the form of climate change, warming waters, sea level rise, ocean acidification, microplastics, and more. Perhaps of greatest concern is the cumulative impacts of these persisting, continuing, and emerging threats intersecting within the seascape during more than 150 years of anthropogenic change.

The State of the Salish Sea Report

With the help of dozens of contributors from around the region, this report is an effort to synthesize and characterize the most pervasive problems and state of the ecosystem. For the benefit of all readers, irrespective of current role or interest in the Salish Sea, we end the report with a spectrum of specific needs and associated opportunities for how governments, organizations, and individuals can work together to meet the needs of science and science-driven management for the Salish Sea — as well as questions to open substantive dialogue and prompt collective action across the seascape.

The science presented herein is intended to inform, illuminate, and ultimately ignite deep discussion and meaningful action, from grassroots efforts to large-scale collective and governmental investments. Addressing centuries of degradation, swelling human population, and global climate change requires vision and solutions for the future that are innovative, adapt easily to local needs, and spark change in our collective values and relationships with the Salish Sea.

Regeneration of the Salish Sea will require multifaceted and collaborative approaches that support greater understanding through education and science, plus sufficient political will, public support, and systemic changes. Fundamental alteration of human–environment relationships, coupled with new and ambitious goals, are needed to change the arc of anthropogenic impacts.

We ask readers to consider your roles, responsibilities, and opportunities for caring for our shared waters in the days, years, and generations ahead. Will we choose to work together to make these commitments and investments toward a future of resilience and connection across the Salish Sea?