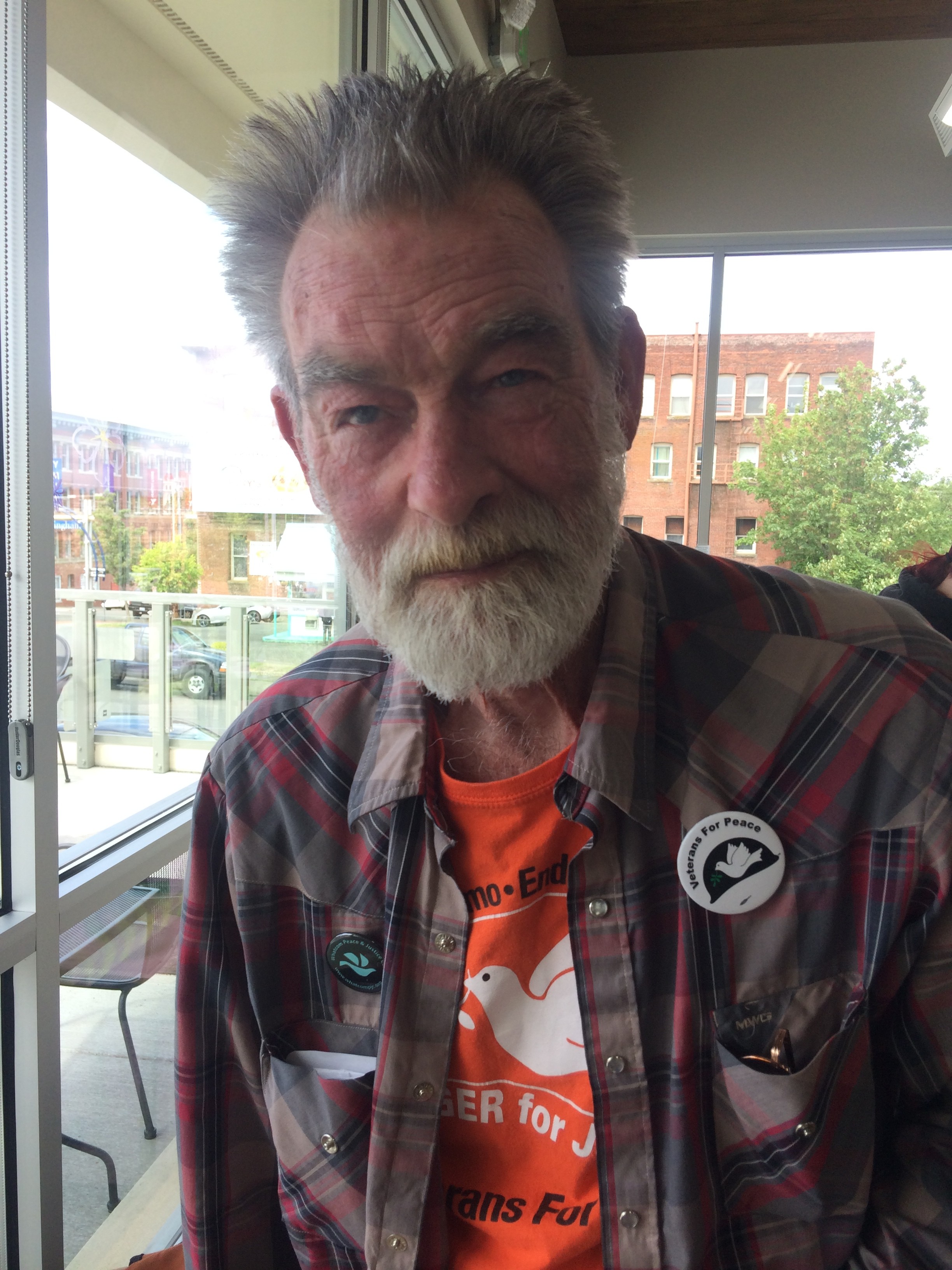

Bill Distler, 69, was born in Brooklyn, New York, and moved to Bellingham in 1980. He is married and has a 16-year-old daughter. He volunteers with the Alternatives to Military Service Program and has been active here in the Veterans for Peace movement since 2004.

Kathryn Fentress: Obviously your time in Vietnam has played an important role in your life. What would you like to share about that experience?

Bill Distler: I was one of the older ones in my unit. I was 20; most of them were 18 or 19. I was in the service 14 months before going to Vietnam. Most of the others only had basic training, four months or so. I was there nine and a half months in 1968. Out of 170 in my company, in the end only 60 were left. The rest were either killed, wounded or transferred to another company that was lacking.

That time still haunts you?

Every 15 minutes or so the memories come back and I sometimes forget where I am going. My friend Willy stepped on a mine and died over there, and his face followed me for about 20 years. When the Traveling Wall Memorial came to town in 1985, someone told me to run my finger over his name on the wall. So I did and then I started crying. After that, he left. I took his following me all those years to mean ‘what are you going to do about war?’

How much time do you still think about the war?

For a long time I’d say about 18 hours a day. Now it is more like nine hours. I worked for 22 years at a flour mill here in town. Sometimes, someone would come up and tap me on my back and I would push them off with my elbow, not even turning around. Sometimes they would ask what my problem was. I would keep working and not answer. Then one day a guy started laughing at me, and I turned around and dragged him to the door and pushed him outside. I always avoided fights growing up so this behavior was out of character, especially the rage that would come up. I had PTSD and thought someone was sneaking up on me. I started crying and realized I was out of control. I wondered why no one had gone to the police and charged me with something. So I figured I should get out before I got into trouble; I quit and began the process of applying for disability. The process took six years before I finally got the 100 percent disability.

What do you tell students you visit in the high schools?

In basic training one of the first things you need to know is what the army will ask you to do. A lot of the training is not about how to defend yourself as much as it is about training you to do whatever they tell you to do without question. It is mind control training. Decency has to be broken down. They prepare you to kill whenever you are ordered to. War does terrible things to people, and the government expects the returning soldiers to re-enter society as if they had never been away. Even now, the government does not take enough care of its veterans. Many wander the streets homeless and addicted.

How do the students respond?

Sometimes they just sit quietly and listen. Sometimes they ask questions. One day I ran into a former student who recognized me from one of those past talks. He told me that before he heard my talk, he had planned to go into the Marines. But after he heard me, he decided that the service was not for him. I felt good that my story maybe saved him and the people he would have killed.

Please explain the work of the Veterans for Peace.

Some Vietnam Vets in Maine started the movement back in 1985. I’ve been active here since 2004. At the height of the antiwar movement during the Iraq war, we had as many as a thousand out on the corner by the Federal building in downtown Bellingham. What I have figured out in my research is that the US military has learned nothing of value since the Vietnam War. What they have learned is how to kill people more efficiently and without raising a fuss. For example, the government has indicated that there are only a few thousand soldiers in Afghanistan currently. However, if you dig deeper, reports indicate that there are as many as 40,000 “contractors” there. I read the New York Times every day and try to figure how and what is going on. There may be only one sentence in a long article that is useful. Most of it is garbage.

What does your local group do now?

We don’t do much demonstrating currently. The peace movement has slowed down. These days, young people are involved with environmental issues. Our local group meets at the new Co-op bakery building on the third Friday evening of the month. We support each other, share our ideas and upcoming events. We may show up for each other’s projects, but we are not demonstrating as a group right now. Some of us talk with students in the schools and counsel students who are interested in alternatives to the military.

I never feel like it is enough — not enough to end the war. If no one else will talk at a school, I will, because someone has to do it. We also have some associate members. You don’t have to be a vet to join. One of our associate members, Ellen Murphy, suggested a while back that we do something as a group to honor the Lummis. We agreed, and she drafted a message of appreciation that we had made into a plaque and presented to some of the Lummi tribal leaders.

For years, I’ve noticed that we are good at identifying what is screwed up but we don’t spend much time on what we could do that is more positive. Complaining is relatively comfortable. We need to combat the negative. Instead, let’s ask ourselves what could we do about anything. There is going to be a big convention of Veterans for Peace in August in Berkeley. I am going to do a presentation; I was reluctant at first but I want to make sure Afghanistan isn’t forgotten.

That’s exciting. Thank you for sharing your research. I think you are onto something important: new possibilities.

We need new ways of thinking and we need to create new things. I plan to tell the audience the bad news first to awaken folks to the problems, but then shift into ‘here’s what you can do to make a difference.’ There is a group called the Afghan Peace Volunteers. They are a multi-ethnic group who wear blue scarves to symbolize that we all live under the same blue sky. Their story will be told at the conference. People need to remember the mothers in Afghanistan who see their children with an arm or leg blown off. They need to know that the Afghan people are more than the stereotypes presented in the media. What we need is consciousness raising. Sometimes it seems like we aren’t getting there, but you have to believe in something. Perhaps it is an article of faith.

How do you keep your spirits up?

My veteran counselor accuses me of being an optimist! I never figured that out before but I guess I am. I do believe things will get better. Maybe I am naïve but I really believe that if we all keep trying and doing what we can do, change will happen. I believe in breakthrough tipping points and that we may be close to one.

Thank you Bill for your service and for turning a soul wound into a voice for peace.

______________________________________

Kathryn Fentress and her husband moved to Bellingham 20 years ago for the water, trees, fresh air and mountains. She is a psychologist in private practice and believes that spirit is in everything. Living in harmony with nature reflects a reverence for life. She delights in finding and meeting those people whose stories so inspire all of us.