Defining “Fair” and Maintaining Public Safety

With capacity set at just over 200 inmates and an actual daily average population closer to 400, Whatcom County’s jail is beyond crowded.

Since 2016, whenever the jail has reached capacity, both pre-trial inmates and those serving sentences ordered by municipal, tribal and county courts in Whatcom County have been routinely transported to jail in Yakima County, a three-and-half hour drive away from support networks of family and friends.

Approximately 60 percent of the jail population on any given day may be in pre-trial status, still awaiting initial hearings and bail-setting, or unable to afford bail. Pre-trial detainees are among those transported out of the county. And tight quarters in a crowded jail complicates screening for the large number of detainees with mental health issues.

While the issues are well known by those administering courts and managing the jail, expanding capacity is unlikely anytime soon. A proposal to raise funds to renovate, repair and expand the county’s jail facilities and to improve community-based mental health treatment, detoxification and other efforts to keep people out of jail and the criminal justice system was rejected by 59 percent of voters last November. A similar proposal was voted down in 2015.

So, what to do?

Courts across the county are implementing alternatives that keep people out of jail to help alleviate crowding, avoid cross-state travel time and cost and provide better conditions for the substantial number of people suffering from mental illness who end up in jail. One of the key alternatives is to use ankle bracelets, which allow people not deemed a safety risk to go on with their lives while meeting legal obligations. The bracelets use electronics to monitor alcohol use, geographical location and is one of several successful tactics helping to relieve the crush. And save money.

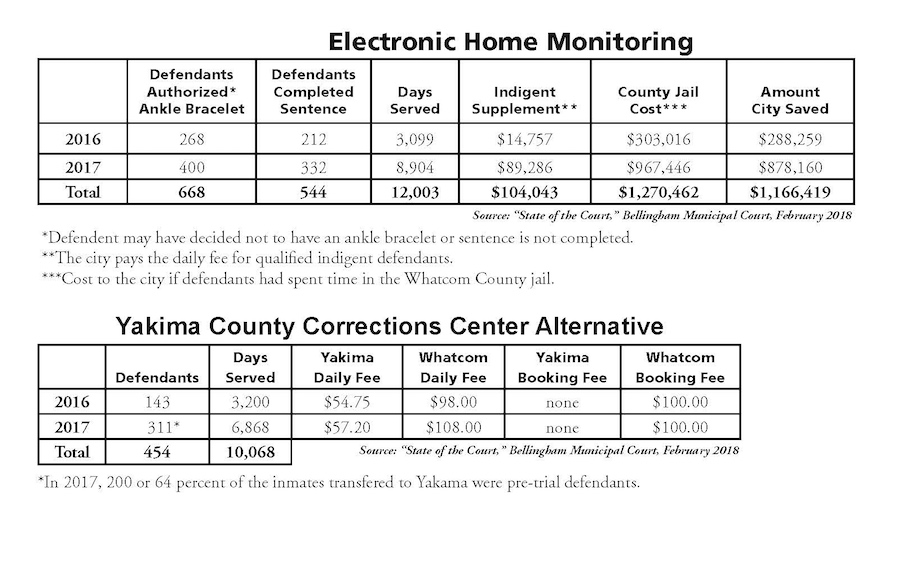

In 2017, 332 defendants from the City of Bellingham completed serving their sentences on electronic home monitoring*, which involves the bracelets. They served 8,392 days at a cost for the service at $89,285.64, according the Court Administrator Darlene L. Peterson. That program saved local taxpayers $878,160.36, based a daily jail rate of $108.00.

The ankle bracelet program showed another success – 98 percent of those authorized for that program successfully completed their sentences.

The electronic monitoring program used by Bellingham Municipal Court is determined by the judge on a case-by-case basis, contingent on risk assessment, best practices and experience gained since Bellingham began using the program in 2016. Municipal Court hears misdemeanor cases for offenses such as shoplifting, driving under the influence, traffic cases, disorderly conduct, and others.

“We’re concerned with safety of protected parties and the general public, and with keeping individuals out of custody when appropriate,” said Bellingham Municipal Court Judge Debra Lev.

How the Bracelets Work

Two types of bracelets can be used.

One uses GPS (global positioning system) technology to track the location of the wearer. The judge determines if an individual is allowed to go to work, keep medical or mental health appointments or meet other commitments. This enables people to continue to care for their families, keep their jobs and stay on track with treatment programs and healthcare.

The GPS bracelet provides continuous, precise information on an individual’s location, said Barbara Miller, Executive Director of the not-for-profit Friendship Diversion Services which provides the bracelet program to Bellingham Municipal Court. The system can be programmed to report when the wearer enters a restricted zone, thereby enabling authorities to keep defendants away from those protected by court orders and immediately alerting authorities to violations.

The GPS bracelets also remind defendants about where they are not permitted to go, Lev said. This is particularly useful for those with mental health issues that can interfere with remembering or following directions — including court orders to stay away from particular areas or businesses.

The other is a SCRAM (secure continuous remote alcohol monitoring) bracelet which is used when the defendant has been ordered to abstain from alcohol. It uses gas spectroscopy to detect the unique chemical signature of alcohol and alerts the court when alcohol has been consumed. The data the SCRAM bracelet provides is “incontrovertible, and has been tested in jurisdictions throughout the country,” Miller said.

By all measures, the bracelet program is working well for Municipal Court, Administrator Darlene Peterson and Lev told the city council’s Criminal Justice Committee in a State of the Court report in February.

Significantly, Bellingham Municipal Court had an “unheard of” success rate of 98 percent of those serving their time on the FDS bracelets in 2016 and 2017, Lev said. Using the bracelet, the judge can direct the defendant to begin serving a sentence immediately rather than wait as much as 30 days to report back to begin serving the time.

“We tell them, ‘This is jail; you just don’t have to go inside the jail to serve your sentence. You can’t go through the drive-through at McDonalds, you can’t go to the AM/PM to get cigarettes.’ We know where they are, we track them, and when we see notices of violation, we deal with it,” Lev said.

The Lummi Tribal Court has adopted several alternatives including electronic monitoring to reduce incarceration of pre-trial defendants and reports a significant drop in the number of people incarcerated.

The bracelet program has decreased the number of warrants for those not reporting to serve their sentences and time-consuming follow ups for police officers and the court. The bracelets reduce incarceration costs as well, Peterson said. In 2017, daily costs were:

• Bracelets: $14.50 for GPS or $25 for both, with a $50 set-up fee

• Incarceration in the Yakima Corrections Center: $57.20, with no booking fee

• Incarceration in the Whatcom County Jail: $108, with a $100 booking fee

Whatcom County District Court, which also hears misdemeanor cases, is looking at electronic monitoring as an alternative to jail, as are courts in the county’s smaller cities.

Other alternatives to jail are drug and mental health courts, out-of-custody work crews, work release, a fast-track program to move cases more quickly through the system, and increased availability of community-based mental health treatment and detoxification.

A comprehensive initiative launched by the county is looking for expanding options and services.

About two years ago, the County Council established the Incarceration Prevention and Reduction Task Force. Its 24 permanent members include mental health professionals, court and law enforcement representatives, and elected officials.

Their charge is to review the county’s criminal justice and behavioral health programs, and to develop recommendations on how to safely and effectively reduce incarceration of individuals struggling with mental illness and chemical dependency and to minimize jail time for pre-trial defendants who can safely be released.

A work group was recently established by the task force’s Legal Systems Committee to study the feasibility of establishing new procedures that would enable pre-trial release of more people. Headed by Whatcom County Superior Court Presiding Judge Deborra Garrett, the work group members are all involved in trying cases or administering the courts. Superior Court hears felony cases and is part of the state court system funded by the Washington Department of Corrections.

The work group’s goal is to determine what is necessary to establish pre-trial monitoring in all courts in the county, she said. Important questions concern what would be needed for a reliable, credible pre-trial risk assessment tool to aid judges in making decisions about release conditions, and for a robust pre-trial monitoring system.

In recent years, money has been tight for the department, Garrett said, and funds for pre-trial alternatives have been reduced or eliminated. At present, Superior Court has no resources or mechanisms to review or monitor compliance.

Garrett said the work group expects to release some fairly specific recommendations to the task force and the community later this year.

The result needs to be incarceration procedures and protocols that are an accurate reflection of the community, Garrett said. “What we want is a county jail that fits what most of us in in the county think is fair.”

________________________________________

Amy Nelson is a freelance journalist reporting on science, education, and public policy. She lives in Whatcom County.