by Preston L. Schiller and Agnes Isabelle

Car approaching the double train tracks between the Amtrak/bus station and ferry terminal: the bollards preventing vehicles from going around lowered gates will help achieve a quiet zone there.

photo: Preston Schiller

Sleep disrupted in the middle of the night by train horns? Annoying even in a Whatcom Community College dormitory a few miles away from the railroad tracks? Had to cover your ears at times when strolling along the waterfront anywhere between Fairhaven and Downtown or along Roeder Avenue between the Granary and F Street? Wished that you had your earbuds in when you were walking or biking in Boulevard Park or along the Boulevard Trail? Do you live in those parts of the Edgemoor, Fairhaven, South Hill, Old Town, Lettered Streets and Columbia or other neighborhoods that hear the train horns loud and clear 24 hours a day?

Then you are among the thousands of Bellingham residents and visitors, and millions of people across North America who are affected by the extremely loud and frequent blasting of train horns — especially in urban areas where the majority of people live and where the majority of closely spaced track crossings are.

How Is Train Horn Noise Measured?

A standard measure of sound energy is the decibel (dB) or one-tenth of a bel — a metric originating in 1928 when Bell Telephone named it to honor Alexander Graham Bell. It is logarithmic, based on orders of magnitude, rather than a standard linear scale; each decibel increase is quite large. The “3 dB rule” indicates that a 3 dB gain means twice (x2) the power, while a 3 dB loss means half the power. A modified decibel scale in the sound range audible to humans is termed dBA for Decibel A Scale. Due to its logarithmic nature, the difference between the FRA’s minimum train horn level of 96 dBAs, which is already quite loud, and its maximum of 110 dBAs is enormous. How loud train horns are felt is also influenced by several acoustical and atmospheric factors: topology, wind, moisture, etc. But on a clear, still night, you definitely would want to keep the ear plugs handy.

(Source: Preston L. Schiller and various resources cited in the references)

Trains are noisy even without sounding their horns. Often the vibrations caused by trains rumbling along can be felt at a distance and may damage nearby buildings. Add extremely loud train horns, especially at night, and you have the potential for sleep disturbance and a considerable health issue. Although train horns have been part of the soundscape for a long time, they became much, much louder after the U.S. Federal Rail Administration (FRA) mandated an increase and standardization in their decibels and duration beginning in 2006. It is possible that, over time, some people affected by train horn noise become accustomed to it and stop worrying about its health and sleep interference effects. But their minds and bodies may be slowly and insidiously feeling the effects.

In 2007, educational psychologist and Whatcom Watch stalwart Helen Brandt counted train noise as among many sources of noise threatening Bellingham residents’ health and wellbeing. The serious adverse effects of noise pollution have been well documented in numerous sources cited in the bibliography for this article, but, in contrast to countries like Germany, the United States is doing little to nothing at any level of society. Among Ronald Reagan’s early actions was the ending of noise research at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), as well as solar research at the Department of Ecology (DOE).

Dampening noise from some sources may be beyond a city’s authority, but quieting train horns is something that that cities can address, albeit with considerable effort, expense and patience. This article explores how train horn noise has become amplified in recent years, what actions the City of Bellingham (COB) has taken in response, and what remains to be done before this source of noise is diminished.

Quiet Zone Problems

There are approximately 160,000 railroad track miles and approximately 250,000 at-grade crossings in the United States. Since road and street densities are greater in urban than in rural areas, it is to be expected that the vast majority of these crossings, and train-horn-noise affected areas, would be in the more populated parts of the country.

A local jurisdiction’s only effective option of quieting the train horns is through creating a “quiet zone,” typically at least half a mile long in length. An alternative offered by FRA is the mounting of stationary directional or “wayside horns” pointing in the direction of traffic at crossings. These do not appear to work as well as creating a true quiet zone, and have been rejected after some trials by some jurisdictions, including some in our region.

Establishing a quiet zone can be very expensive and complicated work. It entails creating a number of physical barriers, improved gates that raise and lower, and signal changes. The work leading up to the crossing is the responsibility of the local jurisdiction, either COB or POB in the case of Bellingham, while any work in or adjacent to the railroad right-of-way can only be done by the railway itself. All expenses for a quiet zone are the responsibility of the jurisdictional applicant. The Federal Rail Administration (FRA) also plays a role inspecting and approving quiet zones. When successfully completed and approved, the trains should cease sounding their horns, except in cases where the train engineer deems it necessary, as when there is work being done alongside the tracks or someone is slow in clearing the crossing.

Train Horn Amphitheater

Train horns are, by design, one of the loudest and most damaging of noises that are allowed to invade our public and living spaces. They have to blast their horns several times at or approaching crossings at a minimum noise level of 96 decibels to a maximum of 110 decibels. This can be the equivalent of being on a runway at Bellingham’s airport within 200 feet of a turbojet takeoff. Such loud noise levels can damage hearing for those exposed nearby and create health issues, such as hypertension and sleeplessness, for those within hearing range.

Much of the South Hill, Fairhaven and Edgemoor rise from the bay in a bowl-like manner, thus creating an acoustical amphitheater for train horns. Train horn noise also inundates parts of Bellingham’s Downtown, Old Town, Lettered Streets, Columbia and Birchwood neighborhoods. Too many people ignore or pay insufficient attention to the health harms of noise, or simply regard it as a relatively harmless background nuisance that one should “get over.”

While BNSF (Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad) asserts that is statutorily restrained from releasing specific information about train frequencies and cargos, it has been estimated that there are at least 24 freight trains per day passing through Bellingham. One might well wonder about from where this transparency blocker emerged. It appears that at least half of them are northbound, hauling coal bound for the Port of Vancouver’s coal terminal or southbound returning empty. Crude oil tanker cars are hauled to and from refineries north of Bellingham, although their shipments are not as routine as are the coal trains. Full or empty, crude oil tanker cars are highly explosive and create environmental disasters when they derail or crash.

When Amtrak resumes its northerly Cascades trains this fall, another four trains per day will be added through Bellingham. All this equates to at least one train per hour through Bellingham. Dozens of train horn soundings per hour … 24/7/365.

Quieting the train horns is an important quality of life and health issue for thousands of Bellingham residents and visitors, but it does not seem to be foremost in minds of our local elected officials. The affected public, too, appears to no longer be pressing public officials to resolve this matter within a reasonable period of time. The good news is that there is quiet on the horizon for the Fairhaven/south Bellingham zone. The bad news is that the Waterfront/central-north zone is probably several years away, possibly a decade, from completion.

How Did This Happen?

In 2005, the FRA announced a new rule governing the sounding of locomotive train horns where streets, trails and highways cross railroad tracks at grade. The mandated decibel level, duration and sounding pattern were, overall, increased and standardized. Prior to the new rule, some train horns were a little louder than 110 decibels, some were not, some soundings were of short duration, some were longer — hence, the need for standardization.

The process of developing and implementing this new rule was many years in the making. It appears to have been motivated by a perceived, but insufficiently documented, increase in the number of crashes occurring at crossings, especially at night. The federal government was also upset with Florida’s effort to ban train horns statewide — which was generally not heeded by the railroads. The distance before and after a crossing requiring sounding a train horn was reduced, so the total duration of the train horn sounding was less, leading the FRA to conclude that that the overall noise impact was lessened.

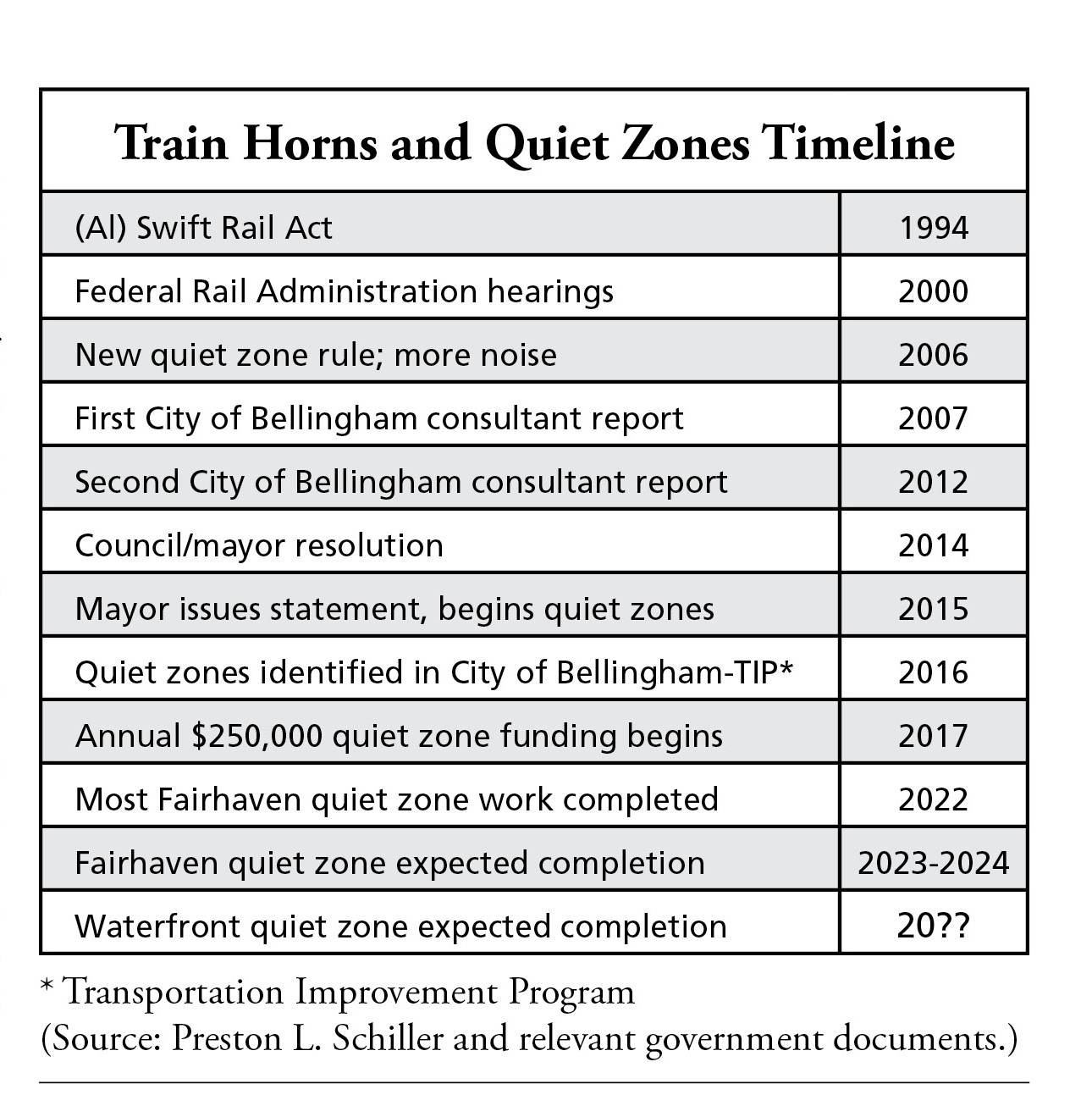

The development of a new rule began in 1996, two years after the Swift Rail Act (see sidebar: Swift Rail Act) authorized such. It was four more years before the proposed rules governing train horn noise levels were vetted in a limited series of public hearings in a few parts of the United States, but not Washington state. As is often the case with such hearings, there was little public notification, and, the changes, which were to affect millions of persons living near railroads, were presented mostly “under the radar” of public awareness.

In 2005, the new rules, increasing both minimum and maximum noise levels, were issued and began to go into effect in early 2006. Railways were given up to five years to change their train horns to meet these levels. It took BNSF only a couple of years to complete the changes. There are several questions and issues which can be raised about the train horn rule (whose answers are beyond the scope of this article, but are important to note). Several of these can be found in the above sidebar: Issues About Rail Act Train Horn Rule and Quiet Zones.

While approximately 2,000 previously existing “quiet zones” (where train horn soundings not allowed by local or state authorities were “grandparented in” under the 2006 FRA rules), only a few hundred have been established or are in the application process since then due to the extreme difficulty and expense of qualifying. There are probably many more areas affected by train horns that would like to be quieter, but lack the resources to make the changes required to accomplish such.

Locomotive engineers can either sound train horns by hand or step on a floor-mounted button for an automated signalling if their hands are full. The FRA Train Horn Rule does not stipulate just how long is a long signal or how short is a short signal, so how long engineers lean on the horn is at their discretion. Just where in the noise spectrum, between an extremely annoying 96dBAs and an excruciatingly painful 110dBAs the BNSF train horns are is uncertain. Sources at BNSF and FRA did not seem to know, other than they believe that the decibel level is set by the horn’s manufacturer — information which appears to be very difficult to obtain.

Bellingham Experiences More Noise

The noise increase after the Train Horn Rule was in place soon became more clearly noticeable to anyone within hearing range of the tracks. Residents and business owners within that range, or close to the tracks, were upset and began to register complaints at City Hall. Several who had looked into the matter proposed that COB address this problem through the creation of a “quiet zone,” which would improve at-grade crossings to a standard where trains would no longer have to sound their horns upon approach unless there was a cause for doing so. In response, COB commissioned a consultant’s study of what might be involved in creating a quiet zone.

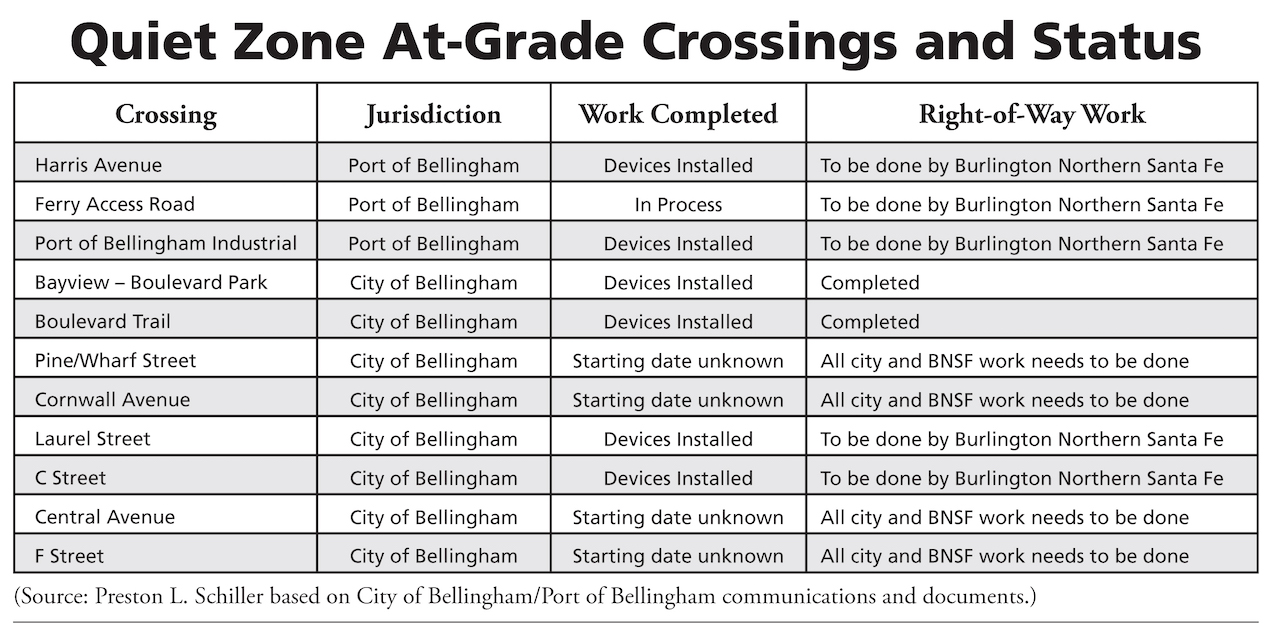

In 2007, the HDR’s (a top transportation engineering firm) consultants’ study was released. It is mostly a technical report, detailing how two quiet zones could be created. The Fairhaven Quiet Zone would encompass several crossings, ranging from Harris Street at Fairhaven Station and the Port of Bellingham (POB) crossings a short distance to the north of the Bellingham Ferry Terminal to the Bayview entrance and trail crossing at Boulevard Park. The Waterfront Quiet Zone encompasses all the crossings between Wharf-Cornwall and the F Street switching area. The city was slow on acting on the report, possibly due to the economy’s downturn, and the port was even slower in addressing its responsibilities.

In 2012, an addendum to the 2007 report was prepared by MCR Logistics in response to cost changes and some changes in the FRA 2006 train horn rule, as well as a possible railroad siding that might be built to accommodate additional train traffic serving the coal terminal proposed for Cherry Point. The FRA rules did not change the 2007 HDR proposal, and, fortunately, the coal terminal proposal was rejected due to a great deal of citizen and elected official opposition. (Note: see Schiller’s series of 12 Whatcom Watch articles, 2011-2012, about the coal terminal proposal and coal trains.)

By the end of 2014, the Bellingham’s City Council passed a resolution in support of and authorizing the mayor to establish quiet zones within the city limits. Some planning and work had already been done to improve the Boulevard Park Trail crossing, perhaps in reaction to a cyclist fatality there. Funding to support this effort began to appear in COB’s annual Transportation Improvement Program of 2016 as “unfunded,” and, in each year since then, in the amount of $250,000.

It’s Complicated

Achieving a crossing improved to the federal Quiet Zone standards is very complicated, due to the demanding safety features and that the railroads, themselves, control all work done in or adjacent to their rights-of-way; these might involve changes in the signals, signage, electrical, etc. It is especially complicated for Bellingham because it has a large number of crossings, each with differing situations — from crossings solely on POB properties, some which serve limited purposes, such as a shipyard or boat ramp, to busy city arterials connecting important public facilities, such as the ferry terminal or parks, to pedestrian and cyclist trail crossings. The jurisdictions which control the land adjacent to the crossing, such as COB and POB, must pay for all quiet zone expenses.

To date, COB has completed its share of crossing improvements for the Fairhaven Quiet Zone and has begun funding a few and planning for the remaining crossings in the Waterfront Quiet Zone. It intends to use federal (TIP) funding, some funding from street resurfacing funds, and $2,690,000 in federal grant funding for the F Street/Roeder Avenue at-grade crossing of the Waterfront Quiet Zone section. But these are very complicated crossings and will likely take at least several years, possibly 10, to complete.

Only a relatively minor amount of work needs to be done by POB to its Alaska Ferry access crossing in order for the remaining railroad right-of-way work to be done by BNSF in conjunction with the port. The port estimates that, depending on when BNSF fits it into their schedule, it could be done by late spring 2023 — but, given the complexities of working with BNSF, it will probably be the winter of 2023-2024 at the earliest. Then, COB will take the lead in requesting that the FRA inspect and approve all the work done at the five crossings comprising the Fairhaven Quiet Zone. With luck, and cooperation from BNSF and FRA, the Fairhaven Quiet Zone may be realized before the end of 2024.

One could not, in fairness, fault COB staff who have been working on this issue for several years. They are doing an excellent job given the hand they have been dealt: years of delay before the city council and mayor began to address and fund this matter, annual funding insufficient to expeditiously execute improvements, etc. The port appears to have been even slower than the city in addressing this matter, but its staff have picked up the pace in recent years.

The greatest part of the burden lies with the federal government and its elected and career officials who seem less than eager to challenge the status quo of powerful freight railways, as well as all the problems of an understaffed, underfunded, and, possibly, overly cautious FRA bureaucracy. The railways are generally less than cooperative. On the basis of possibly flawed research, they seem to believe that quiet zones are more dangerous than those where horns are sounded — despite improved gates, physical features that prevent vehicles from going around gates, improved signals, and a small amount of mostly insoluble motorist, cyclist and pedestrian orneriness about heeding signals and gates.

Train Horns in a Noisy World

Given the large number of actors involved, the slow pace at which some of them address their responsibilities in regards to establishing quiet zones and the uncertainty of how much more funding may be required, it is unclear as to how much longer the Quiet Zone project will take before there is relief from the train horns throughout Bellingham. Whatcom County was able to achieve a quiet zone at a crossing just south of Bellingham, but it was a relatively simple and inexpensive fix.

Meanwhile, keep the ear plugs handy and think about all the other harmful and unnecessary noise sources we are tolerating that also merit quieting: leaf blowers, weed eaters, unmuffled or poorly muffled lawn mowers and motor vehicles, alarms going off for no reason, mobile phone users loudly sharing their speaker phone conversations, cars and neighbors sharing their bad taste in something they consider to be music, constant traffic noise on busy streets — the greatest source of urban ambient noise — what did you just say?

(The authors would like to thank Eric Johnstone, Chad Schulhauser, Chris Comeau, Public Works Department, and Councilmember Michael Lilliquist of the City of Bellingham; Greg Nicoll of the Port of Bellingham; Johan Hellman of BNSF; and Warren Flatau of the Federal Railroad Administration for providing extremely helpful information. Assertions and conclusions expressed are strictly those of the authors.)

The Irony of the (Al) Swift Rail Act (SRA)

In 1994, Congress passed a wide-ranging bill addressing several aspects of railroad planning and funding. The Swift Rail Act was named in honor of Washington Congressional Representative Al Swift, who represented the district that included Bellingham, and who played a major role in its enactment. Rep. Swift was an influential member who played a prominent role in clean air and transportation legislation, among others of his interest. As a citizen lobbyist for the Sierra Club, I met with him on several occasions and even encountered him after his retirement when he worked for BNSF in an executive capacity. He maintained an official residence in Bellingham and served the city well, bringing home funding and authorization for the ferry terminal and Amtrak station in Fairhaven, among other projects.

In a spirit of bipartisanship, now all but disappeared, Washington Republican Senator Slade Gorton gained acceptance of naming the act after Al Swift and helped move it through the Senate. Most of the emphasis of the Swift Rail Act (SRA) was on promoting and funding high-speed rail in the United States. But, a significant portion was also focussed on railroad safety. This section laid the groundwork for the Federal Rail Administration (FRA) to regulate and standardize the treatments for at-grade rail crossings and local efforts to create quiet zones to diminish train horn noise.

The SRA mandated the sounding of train horns at all at-grade crossings and preempted all local and state level restrictions on train horn noise. While the SRA allowed for the creation of quiet zones by local jurisdictions willing to fund and create numerous safety measures and cooperate with the local railroad entity and the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), it did not allow for the funding of quiet zones, per se, seeing such as local matters not of interest to the federal government. Federal funds, however, could be applied to specific safety measures, albeit such funding has to compete with many other state and local funding requests.

By preempting state and local authority, not authorizing funding for quiet zones, and allowing the FRA to create an unnecessarily expensive and cumbersome, and possibly off-target, approval process, the Swift Rail Act can be seen, perhaps inadvertently, as sharing responsibility for waking residents at 1 a.m., 2 a.m., 3 a.m., or whenever they are in need of more REMs.

(Source: Preston L. Schiller informed by Mark A. Gruenes, cited in References)

Issues About Rail Act Train Horn Rules and Quiet Zones

• Was there a good research and deliberation base upon which the 1994 Swift Rail Act’s safety stipulations were based? The FRA had not yet completed a study of train horns and crossing safety. The law preempted local and state authority over crossings and the ability to create quiet zones — although it did allow for existing quiet zones to continue.

• The quality of the research and lack of cost-benefit analyses upon which the new train horn regulations were based have been questioned by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) and the Government Accounting Office (GAO).

• Was the scope and amount of public outreach done before the rule was issued sufficient? If FRA analysis indicated that at least 10 million persons are adversely impacted by train horns, which probably was a low estimate, was outreach to a few hundred, including special interest groups such as the railways, sufficient? Were citizens and local officials in the affected areas properly notified and engaged through outreach?

• Are louder train horns the best solution to the problem? The problem of crossing crashes is mostly at night; would improved lighting at crossings or brighter locomotive lights be better? Most of the crashes are caused by motorists’ inattentiveness to signals or horns or going around lowered gates.

• Most fatalities caused by trains are trespassers on the tracks away from crossings, some appear to have chosen “suicide by train.” This issue does not seem to have been fully addressed by FRA or the railways.

• FRA and the railways were let off the hook for the costs (liability in general) of improving safety at crossings or mitigating the noise; these were deemed to be state and local issues.

• While some funds from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) could be applied to road safety improvements for at-grade crossings, it would have to compete with other proposed projects in selection processes.

• Although train horn noise affects millions of persons across the United States, it is seen by the federal government and the railways as a local issue; there is no federal funding program to address this and the railways do not believe in quiet zones.

• There appears to have been insufficient research justifying the decibel levels and durations chosen.

(Source: Preston L. Schiller based on Gruenes and CRS and GAO documents cited in References)

BNSF (Burlington Northern Santa Fe:) Neighbor or Friend?

In Bellingham in 2001, apparently in reaction to an engineer’s irritation with a pedestrian crossing the tracks slowly at the then poorly controlled Boulevard Trail crossing, BNSF added fencing and jersey barriers to blockade the crossing, preventing anyone from using this popular and vital trail and park access. This was done without consultation with the City of Bellingham.

It took citizen action and a fence cutting demonstration, led by then Mayor Asmundson, to force BNSF to negotiate with the city about safety and reopening the crossing. In 2018, BNSF walked away from negotiations to sell an abandoned right-of-way, from Roeder Avenue to Meridian Street to the city. This was done with no explanation or further bargaining. This segment would have enabled the city to complete a key segment of the Bay to Baker Trail.

The city had already been hard at work for many years acquiring rights-of-way and constructing a trail connecting Orchard Place to Iron Gate. The promised BNSF segment would have connected that to the waterfront. And, in 2020, BNSF lobbied the Whatcom County Council to end the moratorium on Cherry Point development, ostensibly to clear the way for more crude oil trains for expanded refinery facilities.

BNSF expends a considerable amount of public relations energy touting how energy efficient and cost effective rail transport is in comparison to rubber-tired freight hauling. While technically accurate, one can still wonder about how much they are contributing to climate change, as coal is one of its major cargos nationwide. The bulk of cargo rolling through Bellingham is coal, and many of its other rail cars contain the highly explosive crude oil destined for local refineries.

While a more responsible carrier would dampen coal and cover cars to contain dust pollution — which also imperils adjacent waterways, BNSF only seemed concerned about the coal dust when it began to make their tracks slick and dangerous, not when it was infiltrating residents’ lungs. State government is hamstrung by federal preemptions in dealing with such hazards and FRA does not seem to get very involved until there is a derailment or explosion.

(Source: Preston L. Schiller based on COB and BNSF documents cited in References)

Checkerboards and Railroad Robber Barons

Train horn noise problems are related to the special privileges that freight railroads have been granted throughout their history. There are only seven major long distance freight haulers in the United States, five of which haul most of the freight and comprise broad regional, almost semi-national, monopolies. Not as extreme in their corrupt and arrogant practices as the railroad robber barons of the 19th century, they are still not good neighbors or friends — and Burlington (or is it Buffett)Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) is no exception. They do not see local disruption or making crossings safer as their problems; they expose populations to great risk without adequately informing them (air pollution, coal dust,exploding fuel cars, chemical spills, etc). They often act without deliberation or consultation with those affected. They generally see their responsibilities to large industrial clients as more important than treating people in the communities they roll through with decency and respect.

Railways have received special government treatment since the days of the 19th century “robber barons” — a powerful elite composed of financial, manufacture and transportation interests. This was a time when the wealthy and powerful bribed and muscled their way into greater power and wealth. Railroads were granted a variety of favors, including vast land grants, especially in the West, as incentives to build railroads and made huge fortunes speculating in lumber and in luring immigrants to buy and settle their land grants. Lands were often granted in a checkerboard pattern leading to serious environmental consequences for forests which environmental organizations have since been working to consolidate.

The robber baron era is reflected in the current day by the special treatments, low or no tax rates and various privileges accorded to current multibillionaire interests, including the semi-monopolistic freight railways. Railways can create large amounts of noise and air pollution, and, generally, not be held responsible for damages resulting from such.

(Sources: Preston L. Schiller, informed by Matthew Josephson, 1962, The Robber Barons and other relevant sources)

God Save the Queen’s Train Horns!

Queen Victoria, that is. The Long Long Short Long (train horn signal pattern) is morse code for the letter “Q.” Back when the queen traveled by ship in England, the LLSL on the horn announced this to other ships in the harbor to get them out of the way. When the queen switched to traveling by rail, the same signal followed, and the engineer would do the LLSL coming into the station to allow some space for the queen. When the U.S. railroads began, the tradition from England was maintained as the standard signal and it is still used today, over 200 years later!

(Source: https://railsafetraining.com/ever-wonder-signal-sequence-came/)

References:

A multitude of resources were reviewed by the authors in preparation for this article: academic studies, government documents and reports, journalistic treatments, etc. Because of their large quantity, we have decided to point readers to a sampling of those that they might find most meaningful and helpful. Several of these sites offer compilations of other train horn and quiet zone resources. Additionally, there was extensive email correspondence with the key entities involved in the train horn and quiet zone issues.

• https://cob.org/wp-content/uploads/train-horns-faq.pdf

• https://cob.org/services/planning/transportation-planning/quiet-zones

• https://cob.org/news/2018/bnsf-terminates-sale-of-lower-squalicum-corridor-to-city

• Bellingham, Port of (2018-2019) Various actions regarding the Fairhaven Quiet Zone taken at February 6, 2018, April 3, 2018, June 4, 2019, and September 3, 2019 meetings.

• BNSF (Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad) 2018. Public Projects Manual. http://www.bnsf.com/bnsf-resources/pdf/in-the-community/public-projects-manual-mtm.pdf

• BNSF (2020) Letter opposing Cherry Point Moratorium. blob:resource: http://pdf.js/3c44adc4-94dc-4c5a-a1a8-2dc4a7c8f716#filename=Letter%20–%20Whatcom%20Moratorium%20–%206.2.20%20(Final).pdf

• Brandt, Helen (2007) “Noise Pollution Threatens Bellingham,” Whatcom Watch Online, January, www.whatcomwatch.org (archived)

• Butt, Tom (2014) “Train Horns: A Modern Public Health Plague.” http://www.tombutt.com/pdf/train%20horns%20-%20a%20modern%20public%20health%20plague.pdf

• Gruenes, Mark A. (1999) “The Swift Rail Act: Will Sleepless Citizens Be Able to Quiet Train Whistles, and at What Cost?” https://commons.lib.niu.edu/bitstream/handle/10843/21877/19-2-567-Gruenes-pdfA.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

• Schiller, Preston (2011-2012) 12 articles about coal trains, coal terminal, BNSF. whatcomwatch.org (archived)

• U.S. Congress (1972) Noise Control Act of 1972. https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/Noise_Control_Act_of_1972.pdf

• U.S. Congress (1994). Public Law 103-440, 103d Congress; An Act To authorize appropriations for high-speed rail transportation, and for other purposes. (Swift Rail Act)

• https://www.congress.gov/103/statute/STATUTE-108/STATUTE-108-Pg4615.pdf

• U.S. Congressional Record (1994). High-Speed Rail Development Act of 1994–Message from the House (Swift Rail Act). Volume 140 Issue 146. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CREC-1994-10-08/html/CREC-1994-10-08-pt1-PgH38.htm

• U.S. Congressional Research Service (CRS) 2013. The Federal Railroad Administration’s Train Horn Rule. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20130603_RL33286_a84d33ac5f65a6705f0191d744ceeca8561d2eca.pdf

• U.S. Department of Transportation; Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) 2006. Final Rule — Use of Locomotive Horns at Highway-Rail Grade Crossings. https://railroads.dot.gov/elibrary/final-rule-use-locomotive-horns-highway-rail-grade-crossings-2006

• U.S. Department of Transportation; Federal Railroad Administration; Office of Railroad Development (FRA) 2003. Final Environmental Impact Statement; Interim Final Rule for the Use of Locomotive Horns at Highway-Rail Grade Crossings. https://railroads.dot.gov/sites/fra.dot.gov/files/fra_net/232/HORNS_FEIS_MASTER.pdf

• U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Clean Air Act Title IV – Noise Pollution. https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/clean-air-act-title-iv-noise-pollution

• U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Noise Abatement and Control (EPA) 1974. Information on Levels of Environmental Noise Requisite to Protect Public Health and Welfare With an Adequate Margin of Safety. https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/2000L3LN.PDF?Dockey=2000L3LN.PDF

• U.S. Government Accounting Office (GAO). 2017. Quiet Zone Analyses and Inspections Could Be Improved. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-97.pdf

______________________

Bellingham resident Preston L. Schiller is the co-author of “Introducing Sustainable Transportation: Policy, Planning and Implementation” (2018 Routledge). He teaches a graduate level course in sustainable transportation policy at the University of Washington.

Agnes Isabelle is from Indonesia and has just finished two years of study at Whatcom Community College. She plans to pursue further studies in journalism and political science this fall at the University of California at San Diego.