by Ellyn Murphy and Chris Elder

At a recent meeting of the Whatcom County Climate Impact Advisory Committee (CIAC), County Executive Satpal Sidhu stated that he would like to see our community plant a million additional trees over the next five years in response to climate change. This campaign would be a great educational opportunity for the community, young and old, as well as a tool for combating climate change.

Planting more trees is a good idea. Trees not only play an important role in the mitigation or removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but also in our ability to adapt to a changing climate. Trees along rivers shade the water and lower its temperature, promoting healthy fish habitat. Trees also stabilize slopes and riverbanks and reduce damage from flooding. Trees should be part of any climate adaptation strategy that builds climate resilience for the county.

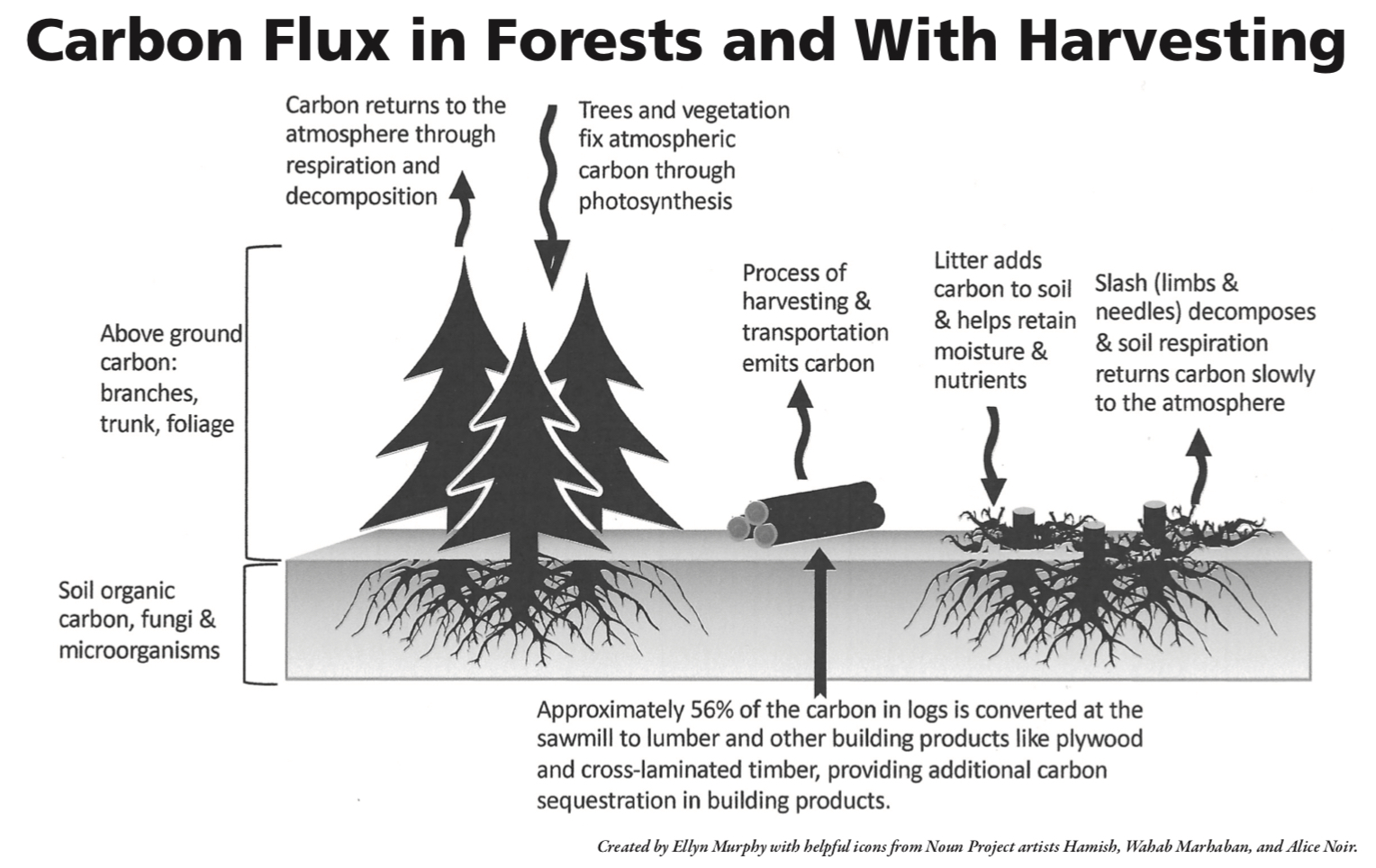

We know that through photosynthesis trees absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide, release oxygen, and incorporate carbon into their stems, branches and roots. A large portion of this carbon can also end up in forest soils. We also know trees emit carbon dioxide during respiration and decay. But, what is the overall impact of Whatcom forests on carbon dioxide mitigation?

We are getting a good idea because county employee Chris Elder responded to a survey from Local Governments for Sustainability (1), the organization that sponsors ClearPath greenhouse gas (GHG) software widely used by local, regional, and state governments to calculate their GHG footprint. As a result of this survey, Whatcom County was one of three pilot jurisdictions in the United States selected to develop and test a protocol for estimating carbon dioxide emissions from loss of forests, as well as carbon sequestered (removed from the atmosphere and stored) within trees and forests.

With funding from two philanthropies, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the Climate and Land Use Alliance, several experts visited Whatcom County in January 2019 to introduce the study and collect data. The team included Donna Lee (Climate and Land Use Alliance), Richard Birdsey (Woods Hole Research Center), and Nancy Harris (World Resource Institute).

You might wonder why greenhouse gases from forests or trees have not been reported previously in emission inventories. The main reason is because the emphasis has always been on emissions from humans and our built environment, often summarized as energy, transportation and waste. Another reason is that “forests and trees often remove more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than they emit, which makes the inventory calculations more complicated,” says Richard Birdsey. According to Donna Lee, “the U.S. Community Protocol did not have an approach to estimate greenhouse gases from land.” This is why these experts decided to develop new guidance for communities — starting with forest and trees.

Fossil fuels are responsible for 90 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Of the total world greenhouse gas emissions, forests sequester about 25 percent of these emissions. While the United States has large areas of forests, they are able to remove only about 10 percent of our country’s total emissions, because the United States emits so much more than most countries. Nevertheless, our expectations were high that forests would mitigate a large portion of our county’s overall annual greenhouse gas emissions, because over 60 percent of Whatcom County land is forested. Therefore, forests represent a potentially large natural sink for carbon dioxide in the county.

Developing Baseline Information

Working with Whatcom County employees, the experts developed a baseline for the annual emissions and removals associated with Whatcom’s forests and other trees between 2000 and 2010. In this study, “trees” referred to trees outside of forestland, such as trees along rivers or trees in your yard.

Reporting on greenhouse gas emissions for forests was based on guidance developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which separates land into six categories — forestland, grassland, cropland, wetland, settlement and other land (barren, snow, ice). Whatcom County encompasses approximately 1.4 million acres, of which more than half (844 thousand acres) are forested.

The impact of forests and trees on greenhouse gas values was estimated for the entire land base of Whatcom County, but the research team also subdivided based on land management approaches (Federal/Tribal lands versus Whatcom-managed land). Whatcom-managed lands was a catch-all that included lands that were managed under county or city ordinances. These lands vary in ownership from the state Department of Natural Resources, to commercial timber companies, to small, privately owned lands.

The team evaluated forests and trees in other types of land. Settlements and grasslands in the county had the highest percentage of tree cover outside of forests at 30 percent. Cropland and wetland averaged about 10 percent tree cover.

Changes in a land use designation can also impact forests. There was a net forest loss of 5,300 acres during the 10-year study period, mostly forests converted to grassland and mostly on Whatcommanaged lands. Normal harvesting of forests does not change the land use category, but does have a temporary impact on carbon dioxide emissions and removals as discussed below.

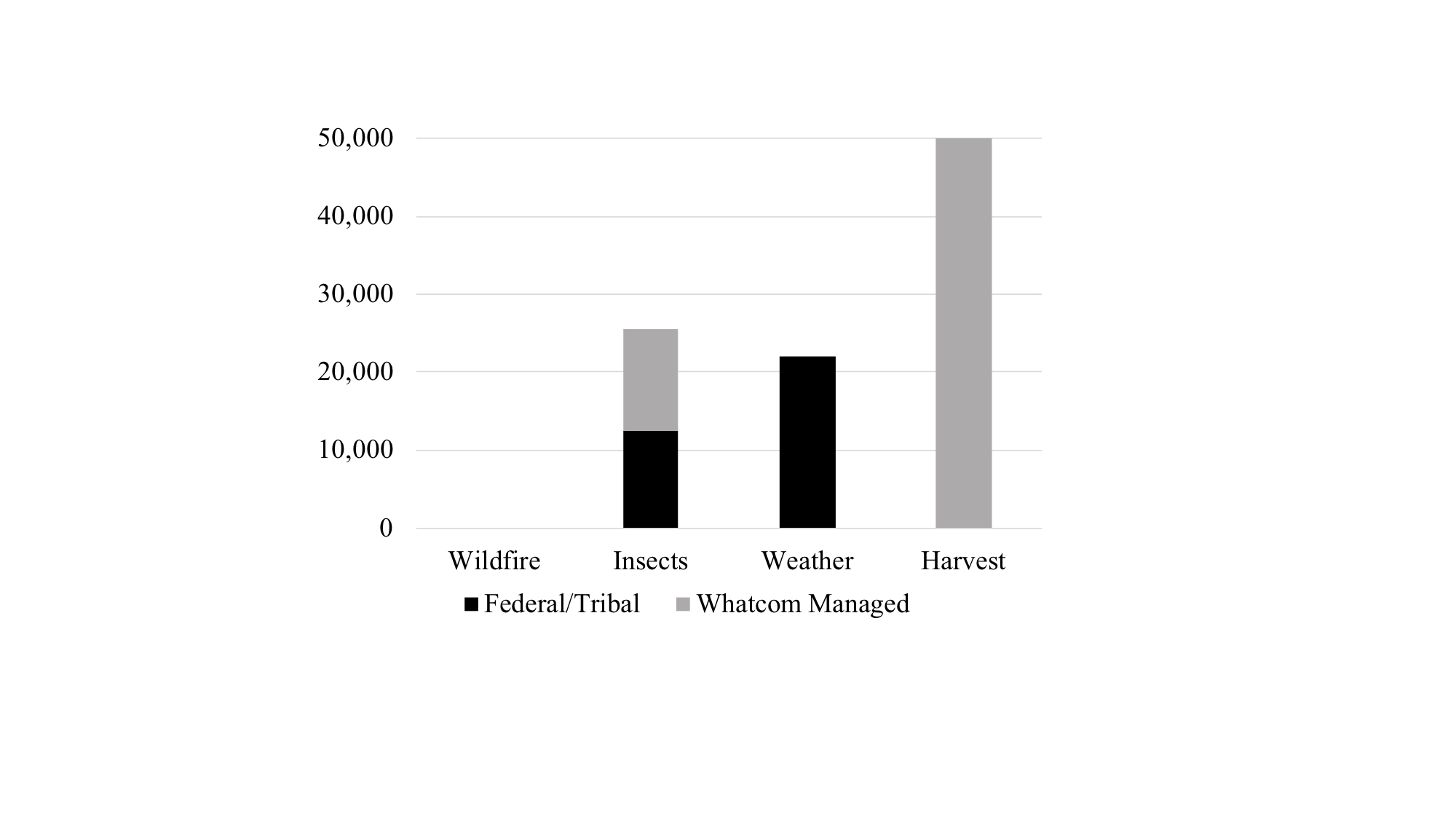

Acres of Forest Disturbance Over a 10-Year Study Period

Credit: GHG Inventory for Forests and Trees Outside Forests by Donna Lee, Nancy Harris and Richard Birdsey, August 2019 report to Whatcom County.

Forest Disturbances

The experts next looked at forest disturbances, which included insects, weather and harvesting in the county (see Acres of Forest Disturbance chart above). Harvesting occurred almost exclusively on nonfederal forestland and was almost 50,000 acres over the 10-year period, or about 2 percent per year. Many local foresters cannot remember the last time there was a timber sale on federal forestland in the county. According to members of the Whatcom County Forest Advisory Committee, most of the timber logged in the county is converted to lumber for construction.

Wildfires result in an immediate release of some of the carbon dioxide stored in the forest ecosystem, but there were no significant wildfires reported during the 10-year study period. Reforestation will increase the amount of carbon dioxide sequestration, or removal from the atmosphere, but slowly over a long period of time. By contrast, when tree loss occurs due to a permanent land use change —for example, when a forest is converted to a settlement — this results in an emission, as the trees are no longer there to absorb carbon dioxide.

Forest harvest is more complex, as explained by Donna Lee, “If the wood extracted from the forest is used for long-lived products — such as building material or furniture — this can result in a positive contribution to mitigation. Building materials store carbon and also replace carbon-intensive materials (e.g. cement and steel) with wood.” So even though harvest emissions can be large, these emissions are partially offset by the increased carbon storage of wood products. This, of course, is assuming that the harvested area is reforested.

Reforestation also helps to remove carbon from the atmosphere. Although young trees sequester carbon at a relatively rapid rate, older trees have a more developed canopy, encompassing more surface area for photosynthesis on a per acre basis. This is reflected in the age categories used for this greenhouse gas analysis, 0-20, 20-100, and 100-plus years. In all tree species used in this study, the 20- to 100-year-old trees had the highest rate of carbon uptake. According to Birdsey, “allowing forests to continue growing without harvesting is an effective way to store additional carbon, as long as there is a low probability of natural disturbances such as wildfire or insect outbreaks.”

Insect damage occurred equally on both federal/tribal and Whatcom-managed land affecting about 25,000 acres. Over 20,000 acres were also impacted by weather, almost exclusively on federal forestlands. This is likely due to the higher elevations, steep rocky slopes that are less protected from wind, and possibly even the age of the stands. Increasing trends in insect and weather damage in the Cascade mountain range are in part a result of climate change.

Carbon Stored by Forests and Trees

How much carbon is stored by forests and trees in Whatcom County? A lot. Whatcom forests and trees store the equivalent of over 400 million tons of carbon dioxide. The mass of carbon stored was based on both tree-species-mix and age range.

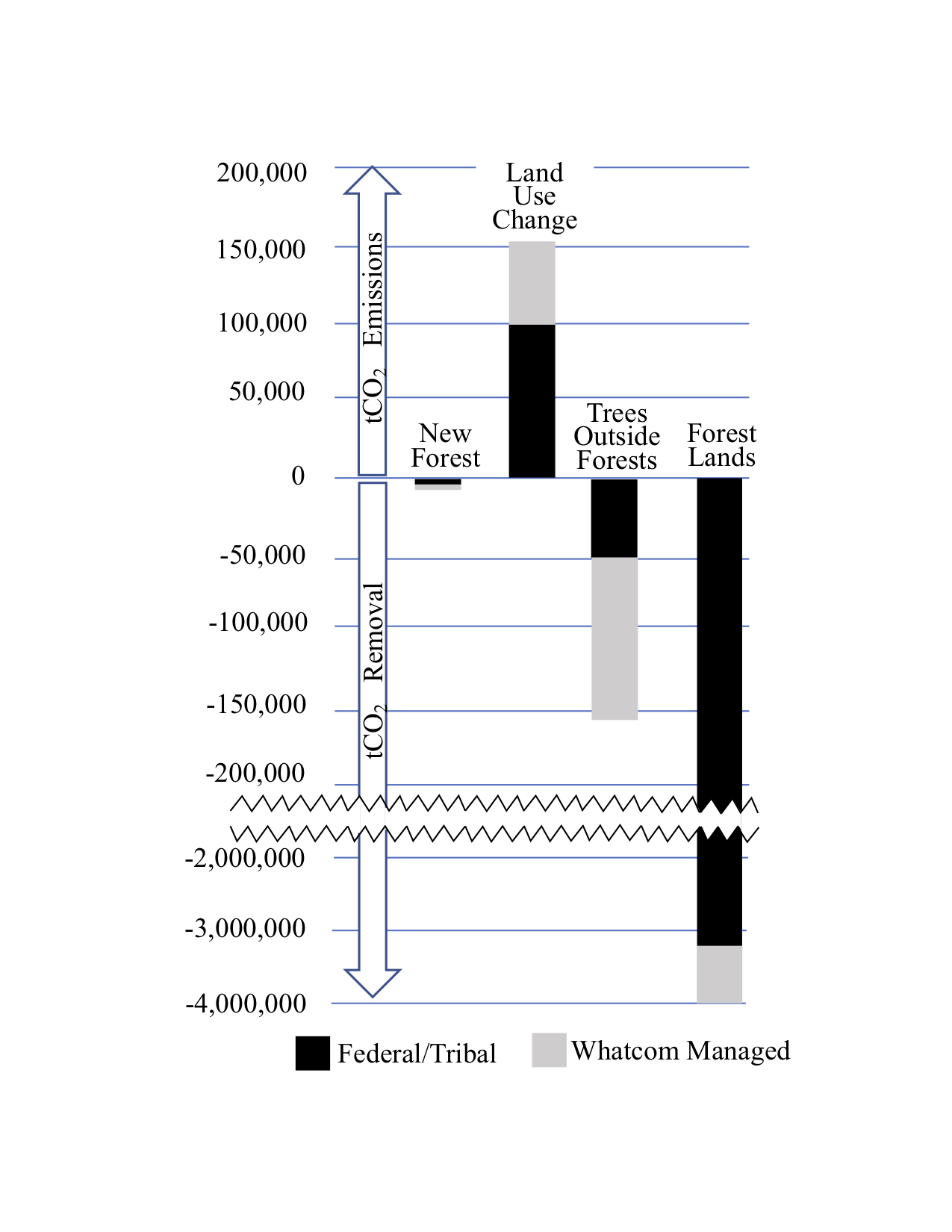

Net Tons of Carbon Dioxide Emitted to or Removed From the Atmosphere

Created by Ellyn Murphy with data from Whatcom County: GHG Inventory for Forests and Trees Outside Forests by Donna Lee, Nancy Harris and Richard Birdsey, August 2019 report to Whatcom County.

Net tons of carbon dioxide emitted to or removed from the atmosphere due to forests and trees in Whatcom County over the 10-year study period. Emissions are positive, while removal or sequestration is denoted by a negative number.

Over the 10-year baseline study, Whatcom forests and trees provided a net removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere of approximately 4 million tons per year. This chart, with the break in the vertical (y) axis may be confusing at first glance. The break was necessary to show all of the data on a linear scale. Emissions of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere is a positive number, while removal or sequestration of carbon dioxide is denoted by a negative number.

The positive emission in this graph, “Land Use Change,” is due to the loss of forestlands over the study period, as land was changed to another land use category: settlement, grassland or cropland. In contrast, “New Forest” occurs when non-forestland is converted to new forests. The bar labeled “Forestland” represents no change in land use (forests remaining forests), and takes into account emissions from harvesting and natural forest disturbances, such as insects and weather.

This chart illustrates that forests in Whatcom County are a net carbon sink, pulling much more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than they emit. Trees outside of forests only represent about 4 percent of the net sequestration; however, if these trees were cut, it would have about the same impact as the deforestation that occurred from land use changes, making them a valuable addition and illustrating why planting trees is so important.

How Can Whatcom County Use This Information?

The 10-year baseline period in this study represents a snapshot in time, but it will nevertheless allow the county to plan for future trends. “Now that the baseline is set for forests and trees, it will be important to update the inventory to see if Whatcom’s forest carbon sink has increased or declined in more recent years,” noted Nancy Harris. Richard Birdsey added, “we are developing software and training modules that will allow cities and counties across the nation to more easily assess forest-related emissions and removals.”

Ultimately, this information will allow Whatcom County to develop greenhouse gas mitigation strategies, develop management recommendations to increase natural sinks for emissions, and track results, preferably on five-year intervals. Can we reduce or eliminate further conversion of forestland or minimize its use for new developments? Can we encourage planting of enough new trees to fully offset our carbon emissions and simultaneously support other co-benefits such wildlife corridors and salmon habitat? Can we encourage new forest management practices to improve forest ecosystem health and carbon storage on private properties and in the timber products they provide?

As illustrated in the questions above, there are many approaches that Whatcom County could review and consider, especially given that we now have an emissions’ inventory of our forested landscape. For example, carbon markets and carbon trading have been identified as an important strategy to offset carbon emissions. An example of a carbon market for forestlands could be as simple as establishing a monetary value on carbon sequestration that would allow landowners to sell carbon credits to companies that want to offset their carbon emissions. This in turn incentivizes landowners to grow trees longer before harvesting because of the added benefit of carbon sequestration and storage.

Carbon markets offer an opportunity to protect county forests from conversion, encourage more sustainable forest practices, and bolster rural economies. Time will tell how the county addresses these issues.

Carbon dioxide has been identified as one of the most significant greenhouse gases impacting global climate systems. Maintaining healthy productive forests in Whatcom County results in large amounts of carbon storage and large removals of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, representing some of the many climate benefits provided by trees. And yes, planting an additional million trees, as promoted by Satpal Sidhu, will only help us combat climate change while promoting this amazing natural sink for carbon dioxide.

Endnote

(1) The International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives, ICLEI, is also referred to as Local Governments for Sustainability. This organization also publishes the U.S. Community Protocol for Accounting and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions.

_________________________________

Ellyn Murphy is chair of the What- com County Climate Impact Advi- sory Committee. She has a master’s in forestry and a doctorate in hydrol- ogy. She spent most of her career at Pacific Northwest National Labora- tory working on energy, environment and water issues before retiring and moving to Bellingham.

Chris Elder is a senior planner in watershed management with What- com County Public Works and has supported agriculture and ecosystem- related long-range planning. He has a B.A. in environmental biology and a master’s in agriculture. Chris worked in agriculture for 10 years prior to joining Whatcom County.