by Hailee Wickersham

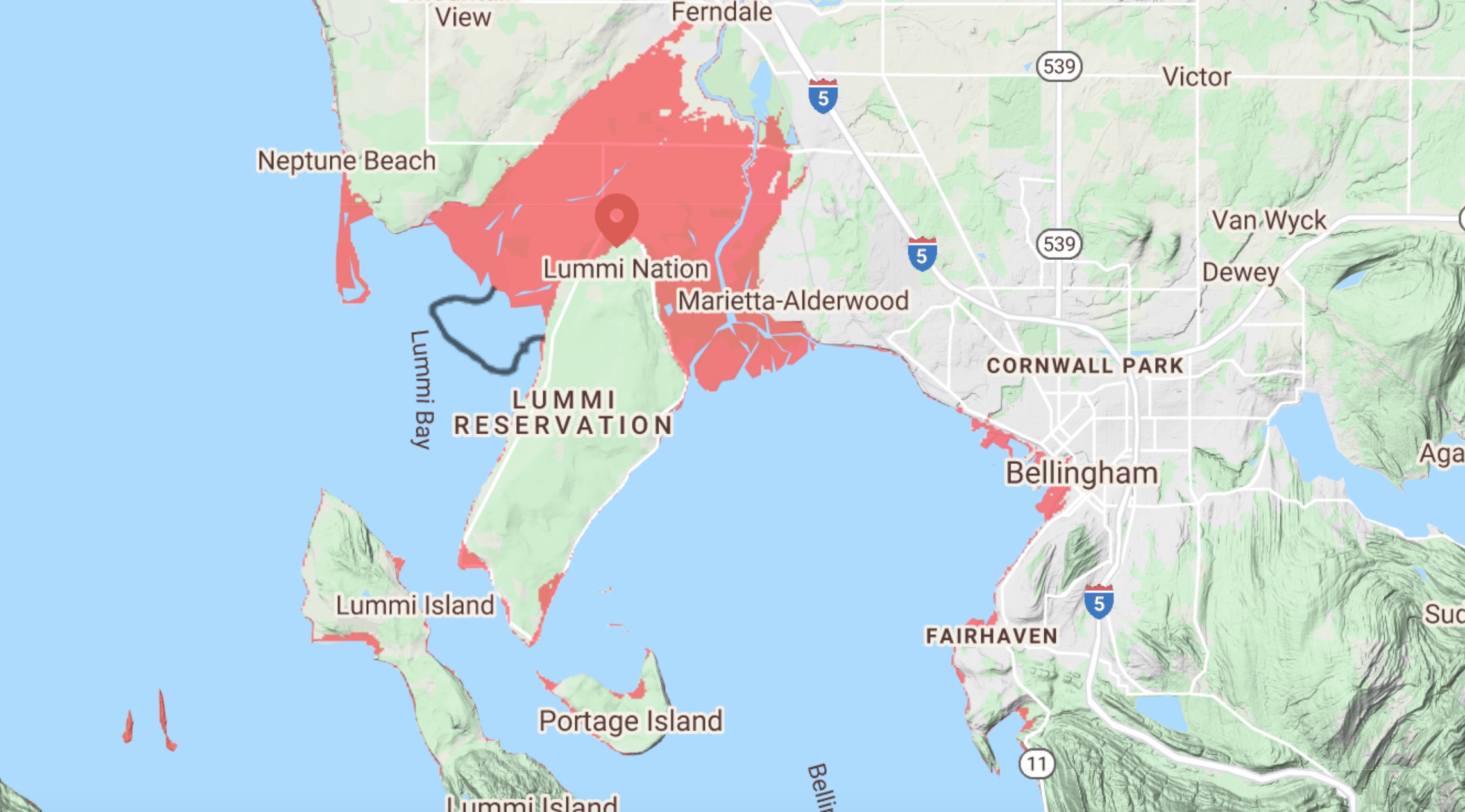

The red areas in this map will be under water with a sea level rise of four feet. The Climate Impacts Group estimates in the report, “Sea Level Rise in Washington State – A 2018 Assessment,” a high-end probability of a sea level rise that will reach reach or exceed four feet by 2100.

courtesy: Climatecentral.org

A coastal modeling program by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has recently been made available to the Puget Sound. The system, named CoSMoS (Coastal Storm Modeling System), has the ability to assess flood risk to certain areas, and has determined Whatcom County as possibly vulnerable to predicted sea level rise.

Global sea levels have been reported as rising for decades. On average, sea levels in Puget Sound have risen by roughly 0.8 inches per decade between 1900-2009, according to the 2020 Whatcom County Climate Science Report.

This equates to roughly an overall 8.7-inch increase in the decades between 1900 and leading up to 2009.

Historical records of increasing sea levels along Whatcom County’s coastlines are not available. But, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Seattle station has one of the longest historical records of water levels in the region.

The Seattle tide gauge has measured relative sea level rise back to 1899. Today, the station records the Puget Sound to have had a mean sea level change of 0.68 feet in the past 100 years.

Sea Level Predictions

According to NOAA, the Earth’s average temperature has warmed by 2 degrees Fahrenheit since 1880. There’s a large body of research and climate scientists that attribute this temperature change to human influence.

Climate Central is a nonprofit organization that conducts scientific research about climate change, with the goal to inform the public on key findings. In recent years, the organization has worked to develop sea-level-rise analysis tools to predict future water levels.

Peter Girard, the media director at Climate Central, explains that, as sea levels rise, coastal flooding increases, which can lead to regular storm events becoming more damaging.

“It’s not a linear relationship, it’s an amplified relationship,” Girard said.

The Surging Seas Risk Finder tool by Climate Central estimates that there is a 51 percent chance of at least one flood over four feet occurring between today and 2050 in Whatcom County. The chance almost doubles to 92 percent when looking at the risk of flooding between now and 2060.

So what things are at risk at four feet above high tide? Well, Climate Central estimates that there are roughly 1,356 people living below that line in Whatcom County. Of this population, 759 people are estimated to be considered high-social vulnerability.

Social vulnerability takes into account a community’s ability to prepare for a hazardous event, such as a flood. Factors such as access to a vehicle, income levels, and housing situations are considered when measuring the social vulnerability of a region.

In addition to the human impact, there are economic risks as well. In Whatcom County, a flood at four feet above high tide could bring roughly $394 million in property damage and take 1,026 homes, according to Climate Central.

An identical flood could also impact 27 miles of local roads, three hazardous waste sites, and four Environmental Protection Agency-listed sites.

“One of the things we remind people of when they look at our risk maps is that these are based on elevation,” said Girard. “So what you’re seeing when you see the dark-shaded area is risk and it is essentially telling you that the land that we’ve identified in those shaded areas is lower than the projected water level in a flood event.”

Climate Central’s Risk Zone Map allows users to toggle between heights of different flood events. In Whatcom County, an unchecked pollution scenario paired with the risk of a four-foot flood shows Bellingham Bay and the Lummi Flats region as the most affected areas.

“The Lummi region is near a [Nooksack] River delta, which is a really common structure to see through low-elevation areas,” Girard said. “That places you at more risk as seas rise and storms become more damaging.”

Coastal Storm Modeling System

CoSMoS, which stands for Coastal Storm Modeling System, has recently made its way to the Puget Sound with the help and collaboration of the Environmental Protection Agency and numerous other partners.

The system was conceptually created by the U.S. Geological Survey for a small region in Southern California in 2011. But since then, scientists have expanded the margins to include other areas of California, Oregon, and Washington.

Dr. Eric Grossman lives in Bellingham and is one of the leading geologists at the U.S. Geological Survey Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center and is involved with expanding the system’s domain to the Puget Sound.

Grossman said that the group is still working on building it out for all of Washington.

“We’re about halfway completed,” Grossman said. “The way to think about in terms of actually constructing this model and completing it is that we built it in, kind of, three sets of models.”

The first model is a regional model that predicts how tides, sea level rise, and influence from storms propagate into the Puget Sound to raise coastal water levels in our bays. Grossman said that this model is largely completed for the state.

The second set of models in CoSMoS includes taking the results of predicted water levels and the effects that could elevate the water’s surface, then running a model for how the waves come onto the shore to break and dissipate.

The last section of the modeling system being built involves taking the results from the first two models to solve for the highest potential reach of water, such as if it goes past a berm or into a coastal plain, said Grossman.

Multiple organizations have partnered with the U.S. Geological Survey to help push the CoSMoS system project forward. Some of the partners are the Port of Bellingham, King and Whatcom counties, and the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, among others, Grossman said.

“What most of us are suggesting as the best use of this information is to look at the range of all the model forecasts,” Grossman said. “Then, as a community, come together and talk about what that might mean, how much impact there might be from the most intense impacts versus the lower ones.”

Moving Forward

As required by the Washington state Shoreline Management Act, Whatcom County began its periodic eight-year review of the Shoreline Management Program in 2019.

The senior planner for critical areas in Whatcom County, Cliff Strong, said that once the amendments are approved by the state Department of Ecology, the program will have its final review by the Planning Commission. He expects any changes approved by the council will be fully adopted into the plan by August to early Fall 2021.

The goal of the periodic review is for the various shoreline management plans to stay up to date with changed circumstances, new information, or improved data.

A portion of the revisions have been adding clarifying language, relocating certain sections, or removing unnecessary wording, but there have been some more notable amendments proposed.

Specifically, Chapter 11 of the Shoreline Management Plan directly addresses the goals and policies for Whatcom County shorelines.

One of the largest changes is incorporating the Shoreline Management Plan policies into Whatcom County’s Comprehensive Plan. County staff has consolidated parts of Whatcom County Code Title 23 and related policies from Chapter 10, Environment, to be encompassed in one Chapter, Shorelines.

Some of the other proposed changes throughout the revised program according to the document are:

• Allowing offsite mitigation within the shoreline plan’s domain when it would better serve critical areas overall. Although, the program would still need to be developed.

• In recent years, it has been proposed to add a section addressing marine resource lands to the county Comprehensive Plan. At the time, the council chose not to adopt the new section and directed it to staff to be considered in the Shoreline Management Program update. It is now being included for consideration.

• Add definitions for language that has specific meaning in the Shoreline Management Program.

• Update vegetation conservation regulations to lean towards limbing rather than removal.

• Provide incentives to enhance Fish and Wildlife Habitat Conservation Areas.

• Review current shoreline guidelines for consistency with state regulations to prioritize living shorelines over hard-armor solutions.

• Where applicable, restore unique resources that have cultural, archaeological, historic, educational, or scientific value or significance to enhance the value of shorelines.

In addition to this, the program has been recommended to develop and expand on current policies that relate to sea level rise and climate change. These newly proposed policies can now be found in their own section of the Shoreline Management Program in Chapter 11.

In the new section, Policy 11AA-5 is among the most notable additions. It reads that Whatcom County should be monitoring the impacts of climate change on local shorelines. In addition to this, the policy requires the county to periodically assess the best available data for sea-level-rise projections and to incorporate findings into future program updates.

The partnership between Whatcom County and USGS to utilize CoSMoS could be considered as taking steps to assess the best available data for sea level rise in our region.

As the county takes increasingly measured actions towards addressing the predictions of sea level rise in our region, Grossman wants readers to consider this:

“I wonder when everyone in our communities will stop and truly think about how they define their well-being,” Grossman said. “When will they honestly evaluate how they feel about their environment changing drastically from climate change? Folks, and I’m one of them, do not fully factor in all of these other non-tangible, non-monetary parts of well-being that make us happy.”

__________________________

Hailee Wickersham is a student- journalist at Western Washington University. You can find more of her work at haileeistyping.wordpress. com