by Stoney Bird and Alan McConchie

Americans across the political spectrum are increasingly dissatisfied with their elected officials. Voter turnout is dismally low. Many citizens feel that their votes don’t count. Despite having it drummed into us that we are a democracy, our country feels pretty undemocratic.

Part of the problem is our voting system, a source of difficulty that many Americans haven’t quite identified yet. For over 200 years, we’ve used “winner-take-all” elections, which turn out to be a major source of the unrepresentative nature in our government. It doesn’t have to be that way. Once you realize that other methods exist, such as ranked choice elections, there is a pretty clear path forward. Both of the authors of this article are active participants in FairVote Whatcom, a local group that advocates for the adoption of ranked choice voting at all levels of government.

First, let’s consider the problems with winner-take-all elections. These are the elections we are familiar with. Whoever gets the most votes gets into office. It’s pretty simple. Therefore it must be right, right? Well, consider a few points.

For starters, in a winner-take-all election, the winner doesn’t necessarily get majority support. If there are more than two candidates, someone can get into office without having the support of most of the voters, while still having more votes than any other candidate.

In Washington, we “solve” this problem by using a top-two primary. As a result, there are never more than two candidates in a general election in this fair state, but we achieve this “solution” artificially. The voters, it is true, were the ones who adopted a 2004 initiative (I-872), putting the top-two in place. A bit of history: The two major political parties appealed the initiative to U.S. District Court and Judge Thomas Zilly overturned Initiative 872; the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with Zilly; the state of Washington appealed that decision to the U. S. Supreme Court, which ruled 7 – 2 to uphold Initiative 872.

The voters had wanted to get rid of the previous kind of primary where voters had to identify themselves as adhering to or the other of the two establishment parties in order to get a ballot. In solving one problem, however, the voters created another.

Having a primary is in itself a problem, though not necessarily related to winner-take-all elections. Relatively few voters participate in the primaries (only 45 percent of Whatcom voters in the August primary this year). And there is significant (and, as we will see, unnecessary) public expense in holding a second election every year.

Wasted Votes

Another problem with winner-take-all elections is wasted votes. These are votes that don’t result in representation. It may seem odd at first sight, but, in winner-take-all elections, a majority of the votes are wasted every election. As an example, let’s consider a 60 – 40 percent election. It’s pretty easy to see that the votes for the 40 percent candidate don’t result in representation — and, in that very mechanical sense, are wasted.

Now consider the votes for the winning candidate. That candidate needed 40 percent of the votes plus one to be elected. The candidate actually got 20 percent more votes than the candidate needed. That 20 percent surplus of votes results in no more representation than the votes for the 40 percent candidate did. So, in a 60 – 40 percent election, 60 percent of the votes are wasted! In fact, in any winner-take-all election, a majority of the votes fail to produce the effect that voters sought when they sent in their ballots: representation. And it gets worse if there are more than two candidates.

When we look at the total popular vote for a legislative body, such as the U.S. Congress, we see the results of these wasted votes vividly. The popular wisdom for the upcoming 2018 election is that Democrats need to win the popular vote by 8 percent to have a chance at winning a majority in the House of Representatives. How is this possible? Where are those 8 percent of the votes going, if not towards representation? Those are the millions of wasted votes in hundreds of districts across the county where the Democrats are winning by too large a margin, “wasting” their votes and not achieving an 8 percent margin in house seats in exchange.

Political scientists have noted the tendency in winner-take-all jurisdictions for there to be only two parties. This comes from the notorious spoiler effect. Many voters fear to vote for the candidate that they really want for fear that it will throw the election to the one they really don’t want. There are two problems here. For one thing, two parties cannot conceivably represent the range of voters’ political perspectives. For another, we surely want an electoral system where voters can freely vote for the candidates that they want, and don’t have to be looking over their shoulders about what other voters are going to do.

Gerrymandering

One of the primary cancers in American political life is gerrymandering. This is the practice where politicians decide who the voters in their district will be (by drawing the lines around the district), instead of the voters deciding who their representatives will be.

People are on the whole familiar with the idea of partisan gerrymandering. This is where one party (that happens to have a majority in the state legislature when redistricting decisions are being made) draws the lines in order to preserve their majority indefinitely. The lines they draw are both for state legislative districts and for national congressional districts.

In Washington state, we do our gerrymandering in bipartisan fashion. Instead of the legislature, it is a bipartisan Washington State Redistricting Commission that draws the lines after each decennial census. The commission is composed of two Democrats, two Republicans and a non-voting chair. Two rather important groups are excluded from this decision-making apparatus: the voters, and, in particular, the Independents who don’t adhere to either of the two establishment parties. This is anything but a disinterested body, making decisions about redistricting objectively in the interests of the voters.

With two of each of them, the two major parties have to agree — and they do agree. What they agree on is that districts should be “safe” and that incumbents should be kept in office. Redistricting is carried out “to preserve the status quo.” And the two parties are very good at achieving their aims. In the 75 congressional elections conducted in Washington state during the last two redistricting cycles (2002 – 2016), only one failed to follow the pattern set by the redistricting commission. That’s a 0.987 batting average! In the legislature, they are not quite so successful — only about .800.

A final point to be made about winner-take-all elections and gerrymandering is that predetermination of election results is inherent. Merely drawing the lines — whether with partisan intent or not — encloses a certain collection of voters. That largely predetermines election results for the indefinite future. So what is the alternative?

Ranked Choice Voting

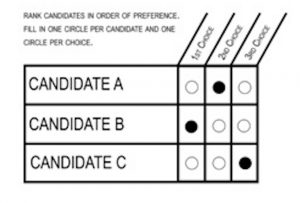

When a voter has a ranked choice ballot to fill out (see example), the voter can express preferences among as many candidates as the voter wants to vote for. If the voter wants to vote for only one candidate, that’s fine, but often there can be two or more candidates that a voter would favor or at least accept, and ranked choice voting allows voters to state these preferences. The Whatcom County Auditor’s Office recently acquired a vote-counting system which is adapted to handling this kind of ballot.

From the point of view of how you vote in a ranked choice voting system, it’s that simple: you rank the candidates that you like.

As for how the votes are counted, let’s take a single-winner election first, like an election for governor or mayor.

The first place votes are counted. If a candidate has a majority, that person is declared elected, and the counting is done. But if no one has a majority, the votes for the last candidate are reallocated based on the preferences stated on each ballot, and the votes are counted again. This continues until someone has a majority and is declared the winner.

The effect of ranking your choices means: if your first choice doesn’t win, your vote may still count towards electing your second choice or a choice farther down your rankings.

If the election is for a body where there are multiple positions (such as a city council or a legislature), you reallocate not just the votes for the last place candidate, but the surplus votes for winning candidates. Both of these kinds of votes would otherwise be wasted, and not count towards representation.

The net result of all this in multi-winner elections is that the result is proportional. Every significant group in the electorate can win seats based on their proportion of the electorate. If we were electing the seven-member Bellingham City Council, for example, someone would need just over 1/8 of the vote to get into office. Any group that makes up more than 1/8 of the population could achieve a voice on the council. Compare that to our winner-take-all system where a group making up as much as 49 percent of the population might narrowly lose every seat they contested and find themselves completely shut out of any representation. Under ranked choice voting, this could never happen.

No Need for Primary

We have two candidates in our general elections in Washington state because of the artificiality of the top-two primary. With ranked choice voting, the “primary” and the “general” election, in effect, happen at the same time, cutting public expense. Because voters only have to participate once, and will see that the result will be more representative of their wishes, voters will be more likely to participate — and more likely to be satisfied with the result.

Because voters get to vote for more than one candidate, their second and subsequent choices are, in effect, backup votes. Voting for the person you really want won’t throw the election to the bad guys.

The points we’ve made so far relate to both single-winner elections and elections to a body. They all represent significant improvements to the existing system. Getting rid of gerrymandering, however, would change the face of American politics. As David Brooks recently wrote in an Op-Ed for The New York Times, it is “one reform to save America.”

Gerrymandering is possible with winner-take-all elections because you’re only electing one person. With ranked choice voting, if you are electing at least five positions simultaneously, it becomes practically impossible to draw the lines so as to predetermine the results consistently. The threshold for election is too small a percentage of the overall electorate. Instead of the redistricters, the voters decide who will represent us.

For us at FairVote Whatcom, the choice is pretty simple. Ranked choice voting is a vast improvement over winner-take-all elections. When the Republic was founded in 1789, winner-take-all elections were cutting edge, but now they’re hopelessly dated. Democracies around the world have moved on to better voting methods based on ranked choice voting. Maybe it’s time we too moved to version 2.0 and actually experienced representative government.

_____________________________________

Stoney Bird has written frequently for Whatcom Watch and recently ran for Congress as a Green Party candidate. Alan McConchie is a co-founder of FairVote Washington and FairVote Whatcom. He was born and raised in Bellingham.