by Eric Hirst

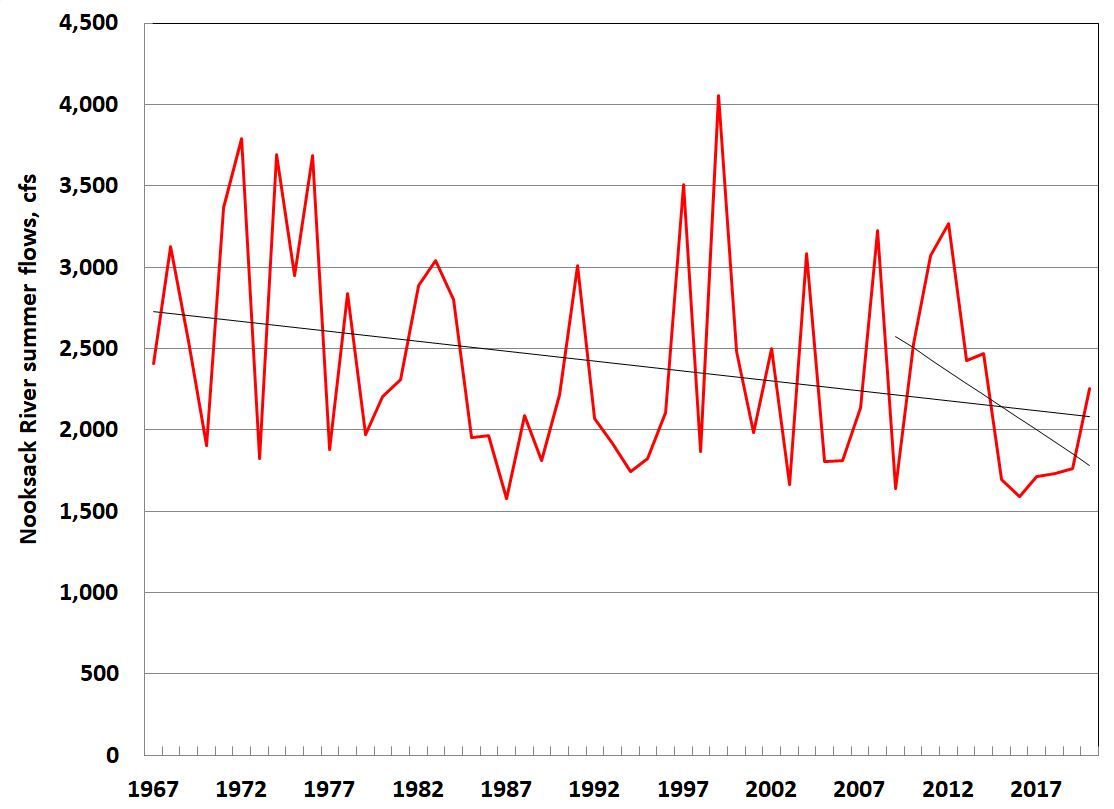

My January 2020 paper published in Whatcom Watch, “Nooksack River: Too Little Water, and it’s Getting Worse,” examined summer flows in the Nooksack River, measured at Ferndale, from 1967 to 2019.(1) These data show considerable year-to-year volatility and an underlying downward trend.

I concluded the paper with this statement: “The simple analysis conducted here for one location on the Nooksack River should be repeated for each of the three forks and several lower Nooksack tributaries to see whether the present results and conclusions are valid throughout the watershed.” This paper examines similar data for the North, Middle and South forks of the Nooksack River, as well as one of the lowland tributaries, Fishtrap Creek. (2)

Fig. 1. Nooksack River summer streamflow at Ferndale, in cubic feet per second (cfs). Summer includes July, August, and September.

Mainstem

Over the past 54 years (1967–2020), summer streamflow, measured by the U.S. Geological Survey in Ferndale, has been declining (Fig. 1). Over this period, flows decreased at an average of 0.5 percent per year. However, this adverse trend is accelerating: during the past 12 years (2009 through 2020), flows declined by 3 percent per year.

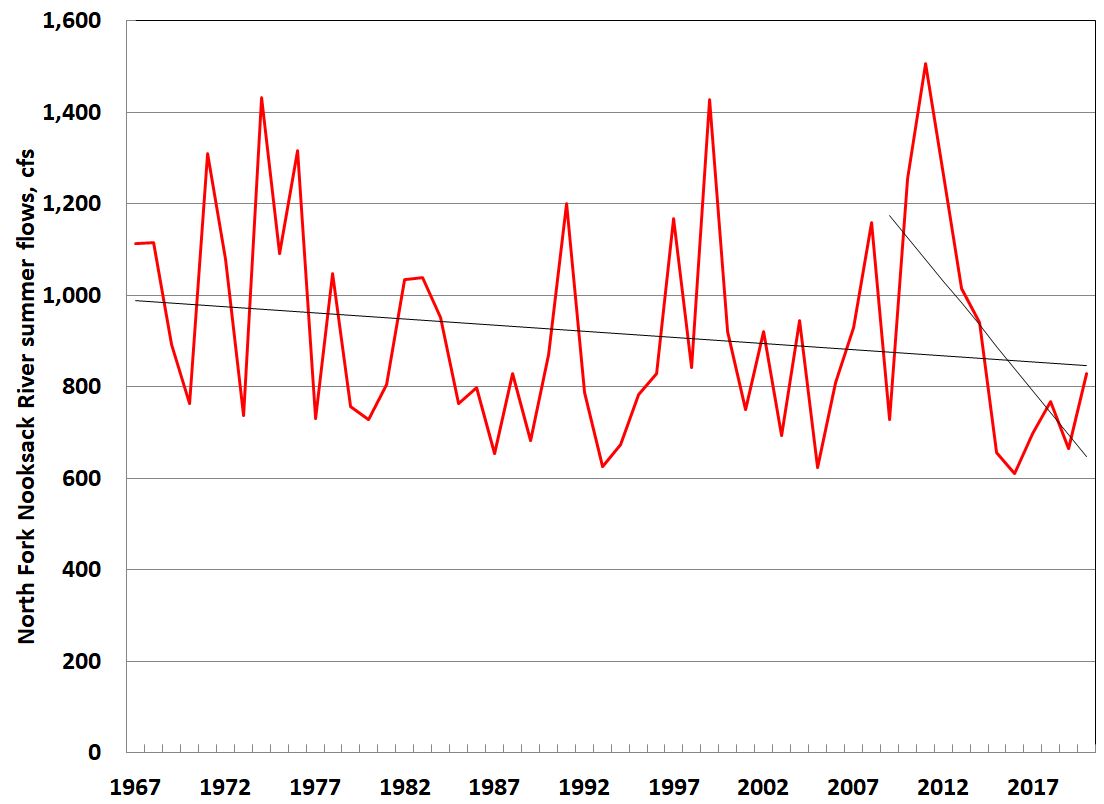

North Fork

Over the same time period, flows in the North Fork, measured at Glacier, show the same pattern as for the mainstem: considerable year-to-year volatility, and an overall decline (Fig. 2). However, the downward trend is less dramatic than for the mainstem: flows on the North Fork declined at 0.3 percent per year over the full 54-year period. However, flows declined by 5 percent per year over the past dozen years.

Middle Fork

Data for the Middle Fork, measured at Deming, are missing for two decades, from 1971 through 1991. Therefore, the results presented here are for the 1992–2020 period, 29 years. Unlike the mainstem and other forks, the trend here is upward. That is, flows increased by about 0.6 percent per year (Fig. 3). However, flows declined over the past 12 years at 2.4 percent per year.

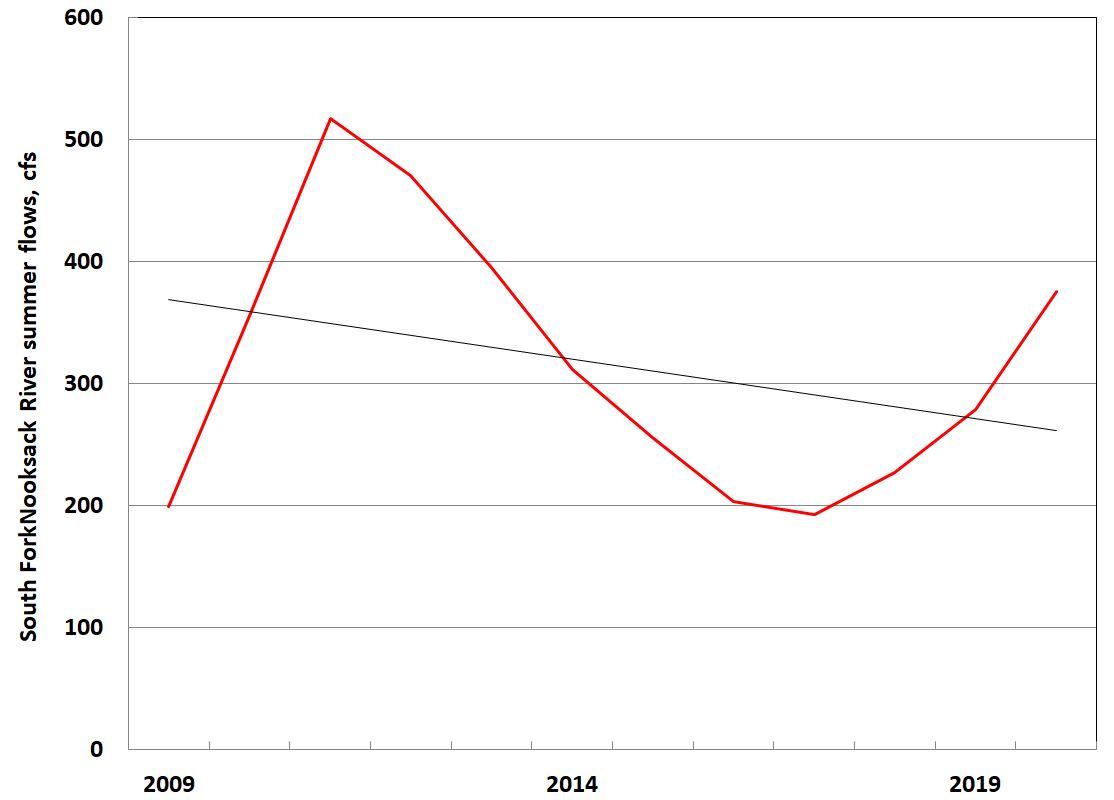

South Fork

Data for the South Fork, measured at the Saxon Bridge, are available only from 2009 through 2020, too short a period to draw meaningful conclusions on flow trends (Fig. 4).(3) From 2009 through 2020, flows declined at 3 percent per year.

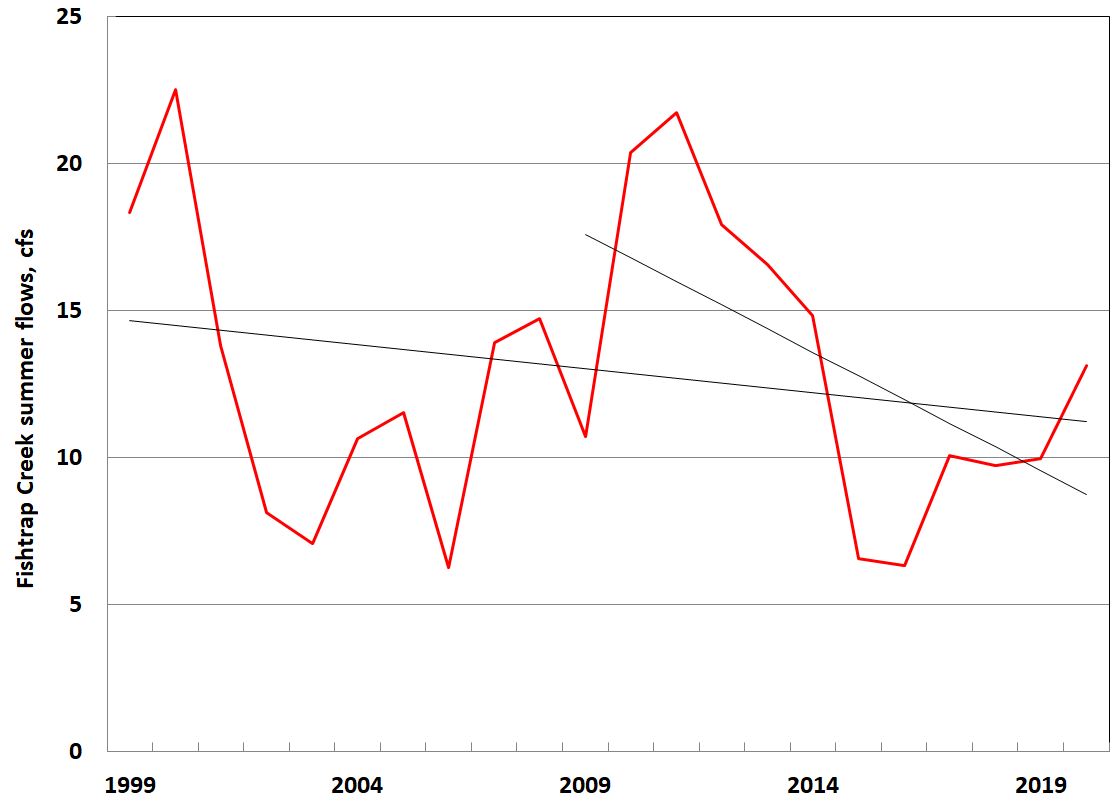

Fishtrap Creek

Data for Fishtrap Creek, measured at Front Street in Lynden, are available from 1999 through 2020, 22 years. Over this period, flows declined at an average of 1.4 percent per year (Fig. 5); over the past 12 years flows declined at 8 percent per year.

The Future

What can we expect in the future? According to the Tribal Climate Tool, flows in the Nooksack River are expected to be lower than current flows (which are, as seen above, much lower than historical) by about 15 percent in the 2050s. (4) Summer temperatures are expected to increase substantially over the next few decades and summer precipitation is expected to decline, leading to greater use of water for irrigation. (5)

Summary

• Overall, flows on the mainstem, forks and one lower Nooksack tributary are declining over time, although erratically and at different rates.

• These declines are worsening over time. Flows during the past 12 years declined more rapidly than during earlier years.

Time Is Running Out

If flows throughout the Nooksack decline at 2 percent per year, flows will be lower by 18 percent in 10 years and by 33 percent in 20 years. (6) Thus, we need to increase flows throughout the Nooksack basin — and do so quickly. For over two decades, we have conducted countless meetings among many groups, produced report after report, and implemented a variety of projects that marginally improved our water supply-demand situation.

But, we have yet to adopt an action plan that includes specific projects to address these water-resource issues, including new supply, storage, and efficiency projects. Implementation would involve identification of specific problems in each basin (three forks, mainstem, and tributaries) and projects intended to resolve those problems. The plan would include budgets, funding sources, organizational responsibilities and accountability, and milestones. Although the 2018-2023 Implementation Strategy, (7) Regional Water Supply Planning Project, and Drainage-Based Management Project are all steps in the right direction, none of them include the elements necessary for basin-wide success.

Endnotes:

(1) I focus on summer because that is when flows are the lowest, salmon and other wildlife are most likely to need more water than is actually flowing, and human use of water is greatest (primarily because of agricultural irrigation).

(2) Information on the various streamflow gauges in the Nooksack River basin and their periods of coverage are in: RH2 Engineering, Whatcom County Streamflow Analysis, Dec. 2016.

(3) Streamflow data are available for Wickersham (about two miles away) through 2008. Lacking a reliable method to convert data from one gauge to another, I deal only with the recent data from Saxon Bridge.

(4) https://climate.northwestknowledge.net/NWTOOLBOX/tribalProjections.php.

(5) H. Morgan, Maps of Climate and Hydrologic Change for the Nooksack River Watershed, University of Washington Climate Impacts Group, Dec. 2017.

(6) Don’t take these estimates literally. Extrapolating a straight-line fit to these “noisy” data would eventually show negative flows in the river.

(7) WRIA 1 Watershed Management Board, 2018-2023 Implementation Strategy, August 1, 2018, Approved updates 09/26/2019.

_______________________________

Eric Hirst moved to Bellingham in 2002. He has a Ph.D. in engineering from Stanford University, worked at Oak Ridge National Laboratory for 30 years as a policy analyst on energy efficiency and the structure of the electricity industry. He spent the last eight years of his career as a consultant. In Bellingham, he has continued his work as an environmental analyst and activist.