by Karlee Deatherage

The small mussel, about the size of a grain of rice, appeared on an aquarium moss ball sold at a Seattle Petco earlier this year. It sounded the alarm across the United States, prompting agencies to work with Petco to issue a nationwide recall of the moss balls, of which about 100,000 had been shipped every two weeks for months to stores around the country. (1)

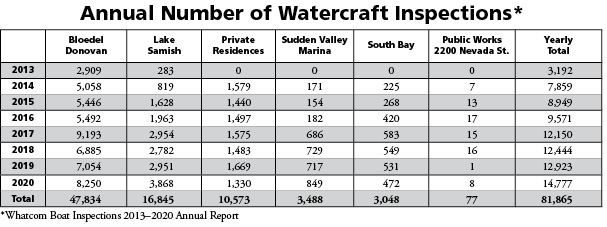

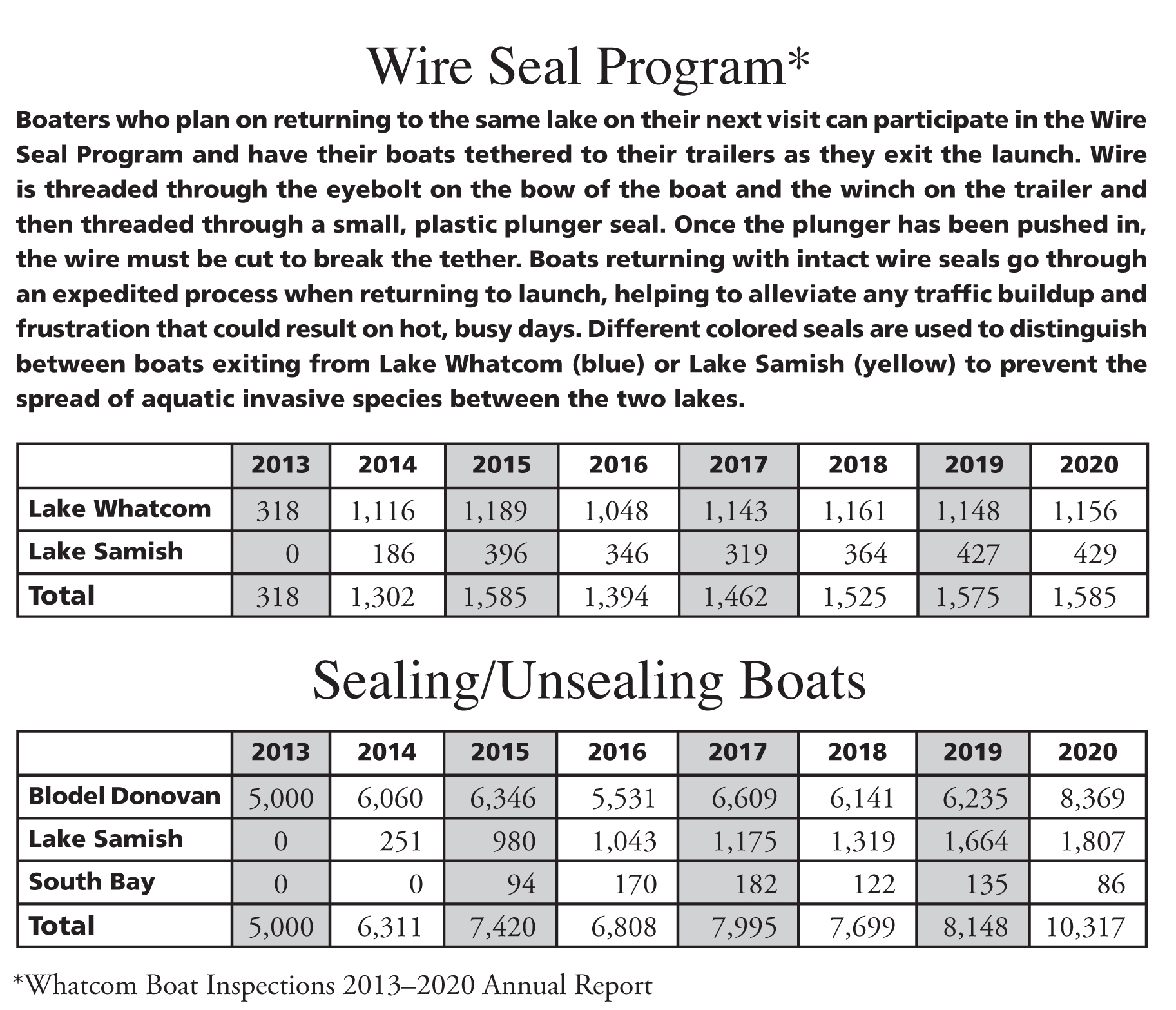

This was the much-feared zebra mussel, which the city of Bellingham, along with many other cities and local governments, has been on the lookout for since 2011. In 2020, boats visited Lake Whatcom from 93 mussel-infested waters, and six full decontaminations were required due to the likely presence of mussels (*see table at the end of this article).

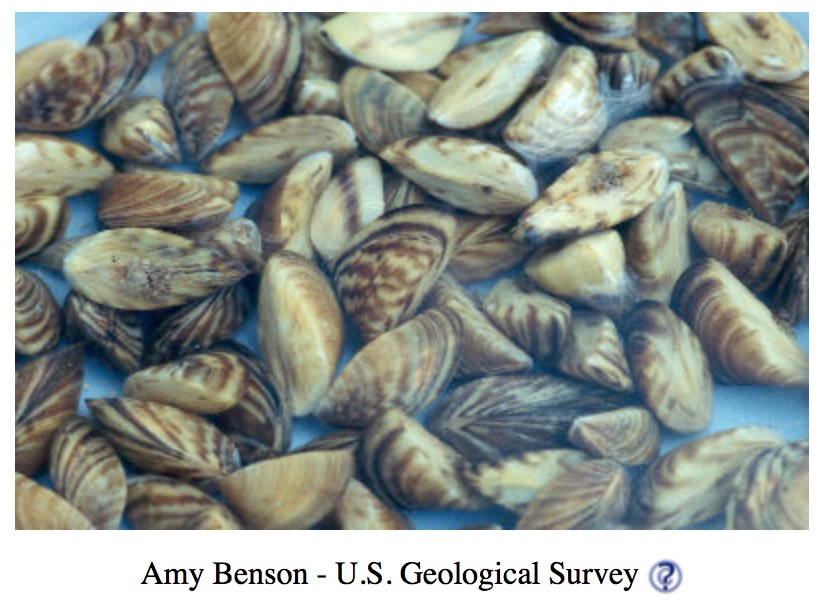

Zebra mussels are one of the most potentially catastrophic aquatic invasive species in the United States. They rapidly reproduce, attach to any surface, including boats and dock pilings, clog water intake infrastructure, disrupt ecosystems, and encourage the growth of toxic blue-green algae by filtering out other types of algae.(2,3)

If the right person hadn’t informed the right agencies at the right moment, the Petco incident could have ballooned into a crisis for drinking water in Northwest Washington.

Native to Eurasia, zebra mussels were introduced to western Europe in the 1700s. They made their way to the Great Lakes Basin in the 1990s, likely by boat, and quickly spread into the Mississippi River watershed. In 2007, zebra mussels were discovered in Lake Mead, Lake Havasu, and Lake Mohave in the Colorado River watershed, likely introduced by a recreational boat. (4)

Zebra Mussels Inching Our Way

Their spread in the West has been slower than the Great Lakes Basin; however, zebra mussels have been documented in Montana and are slowly inching their way to our waterways in the Pacific Northwest. (5)

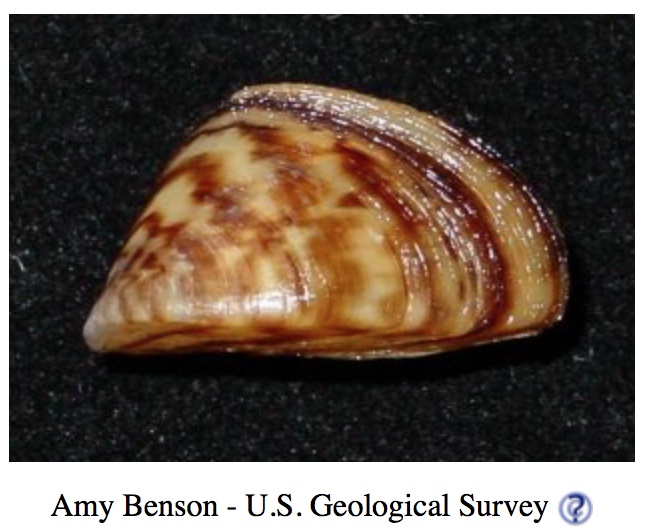

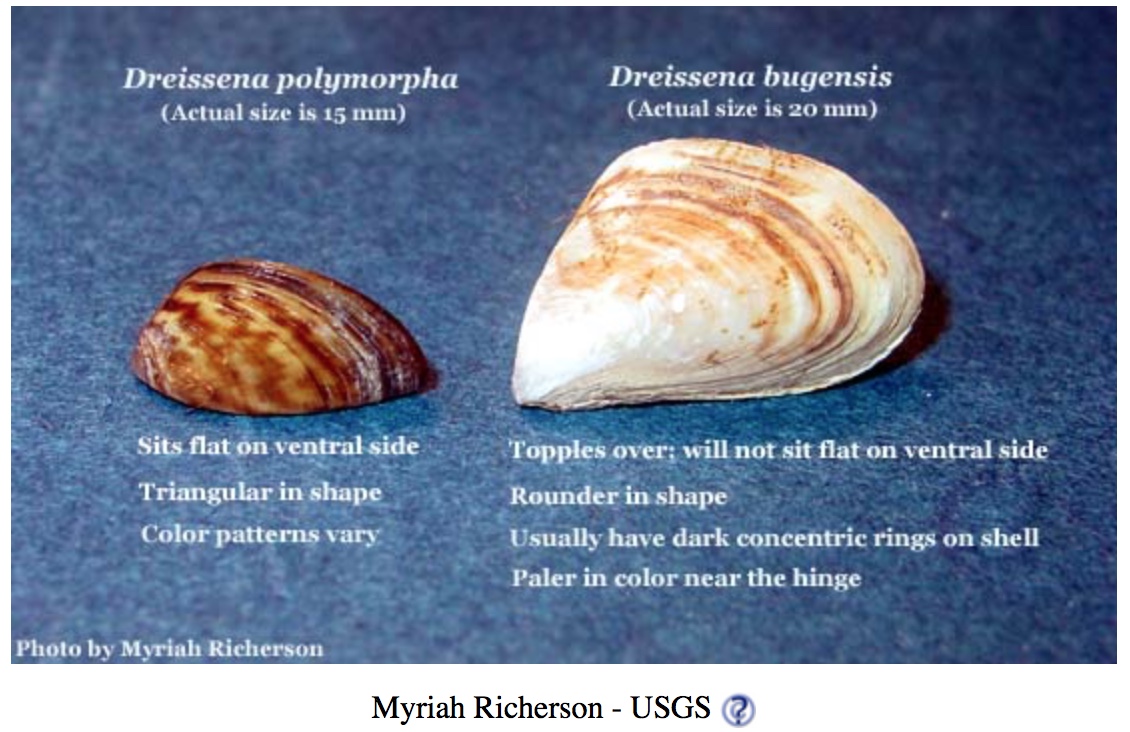

Zebra mussel (left) Quagga mussel (right)

photo: U.S. Geological Survey

https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=5

Lake Whatcom, the largest source of drinking water in Whatcom County serving the city of Bellingham and nearby rural areas, is a recreational boating destination given the plethora of summer homes and vacation rentals and ample space to play across its eleven miles. The city of Bellingham initiated the Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) Program in 2012 specifically to watch for grave, costly threats such as zebra and quagga mussels. Boat inspections started at Bloedel Donovan Park on a voluntary basis and became mandatory for all boats launching at public or private docks in 2013.

Invasive species were already making themselves at home in the Lake Whatcom watershed in spite of the AIS Program. These range from invasive aquatic plants like Eurasian watermilfoil to the Asian clam, which are included on the list of Lake Whatcom’s most unwanted species in the Aquatic Invasive Species Action Plan for Lake Whatcom Reservoir.

Invasive species were already making themselves at home in the Lake Whatcom watershed in spite of the AIS Program. These range from invasive aquatic plants like Eurasian watermilfoil to the Asian clam, which are included on the list of Lake Whatcom’s most unwanted species in the Aquatic Invasive Species Action Plan for Lake Whatcom Reservoir.

Unlike zebra or quagga mussels, Asian clams do not stick to metal surfaces and present a lower impact in that regard. The presence of Asian clams was acknowledged by city staff following the introduction of the AIS Action Plan in 2011, which kicked off the need for monitoring in the lake to track their spread and impacts. There are now 15 sites of established populations of Asian clams, and, as of 2019, they have spread to Lake Samish.

The AIS Program is a risk management program with several loopholes. Boats on the lake are required to have up-to-date inspection stickers as enforced by the Whatcom County Sheriff. AIS inspections at the public launch sites at Lake Whatcom have limited hours during the boating season. But boat ramps don’t have gates to prevent people from launching after hours or outside of the boating season. Someone could launch their boat either at a public launch or private dock with zebra or quagga mussels hitchhiking on the hull or ballast tank. An ensuing infestation could cost millions of dollars annually just to manage the pests or replace water infrastructure, including parts of the treatment facility.

Each year, the AIS program releases a report detailing the number of inspections conducted, the last waterbody a boat has visited, number and types of invasive species intercepted, and much more. The program conducted more inspections and issued more permits than ever last year despite the closure of the Canadian border to nonessential travel.

Thankfully, no zebra or quagga mussels were found at the monitoring sites specifically designed to attract the mussels if they have a presence in Lake Whatcom. We got lucky — this time.

Millions of Dollars Spent

Governments, mainly the city of Bellingham, have spent over $3.4 million (see table on previous page) on the AIS Program since it began in 2013. Revenue from permits covers about one-third of the cost to run the AIS Program annually. Currently, the AIS Program doesn’t spend a significant amount of money as compared to other Lake Whatcom program areas, such as stormwater projects, managing the drinking water utility, and land preservation efforts, according to the 2020 Lake Whatcom Management Program Progress Report; however, that could change with a zebra or quagga mussel infestation.

The Great Lakes have been grappling with economic impacts of zebra and quagga mussels. From 1990 to 2000, these invasive species caused $3.1 billion in damage to water intake pipes and power plants. During the same time period, the impact to private businesses and property is estimated at $5 billion. (6) Nationwide, management costs for these mussels are estimated to be at $1 billion annually. (7) Lake Whatcom, our drinking water source, cannot afford another expensive problem like these invasive species.

The Great Lakes have been grappling with economic impacts of zebra and quagga mussels. From 1990 to 2000, these invasive species caused $3.1 billion in damage to water intake pipes and power plants. During the same time period, the impact to private businesses and property is estimated at $5 billion. (6) Nationwide, management costs for these mussels are estimated to be at $1 billion annually. (7) Lake Whatcom, our drinking water source, cannot afford another expensive problem like these invasive species.

Boats certainly represent the biggest vehicle for invasive species to be introduced into Lake Whatcom. And boats are the easiest factor we can manage by means of policy action. Prohibiting motorized boats from the lake would significantly reduce the risk of introducing invasive mussels; however, there could be legal issues with this approach given private docks.

Whatcom County and the city of Bellingham can close the gap even further to prevent the spread of invasive species by installing gates at public launch sites and extending the inspection presence from April 1 to November 1. The current program opens April 24 and ends on September 30. With climate change extending the warm seasons, more people will boat earlier and later in the year. Whatcom County and the city of Bellingham must make adjustments to their program.

Policy aside, each of us has a role to play to prevent the introduction of invasive species into any waterbody. Clean, drain, and dry your boat and get it inspected if there’s a program. And never dump the contents of your aquarium into a body of water.

A summer of increased tourism and outdoor recreation pressure is fast approaching after a long winter of Covid-19 isolation. It’s never been more important to recreate responsibly, and make sure invasive species aren’t along for the ride during your summer adventures. The source of Bellingham’s drinking water depends on it.

Citations

1. Crosscut (2021). “Zebra mussels on Marimo moss balls are causing an emergency in WA.” Available at: https://crosscut.com/environment/2021/03/zebra-mussels-marimo-moss-balls-are-causing-emergency-wa

2. Science Daily (2009). “Experimental Harmful Algal Bloom Forecast Bulletin for Lake Erie.” Available at: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/09/090917161736.htm

3. Fernald, S.H., N.F. Caraco, and J.J. Cole (2007). Changes in Cyanobacterial Dominance Following the Invasion of the Zebra Mussel Dreissena polymorpha: Long-term Results from the Hudson River Estuary. Estuaries and Coasts 30(1):163-170.

4. U.S. Geological Survey [USGS] (2009). Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database. Zebra and Quagga Mussel Information Resource Page. Available at: http://nas.er.usgs.gov/taxgroup/mollusks/zebramussel

5. State of Montana Natural Heritage Program. Protect Our Waters: Montana’s Response to Aquatic Invasive Mussels. Available at: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=a8f8f3035aae4a54ade5a1fe12606fdb

6. Lovell, S.J. and S. F. Stone (2005). The Economic Impacts of Aquatic Invasive Species: A Review of the Literature. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, National Center for Environmental Economics.

7. Pimentel, D., R. Zuniga, and D. Morrison (2005). Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecological Economics 52:273-288.

_______________________

Karlee Deatherage is the Land & Water Policy Manager at RE Sources. Founded in 1982, RE Sources works to build sustainable communities and protect the health of northwest Washington’s people and ecosystems through the application of science, education, advocacy, and action.