by Peter Heffelfinger

Garlic and Shallots

Just before Halloween, the early fall rains finally ceased and the clay soil in my garlic and shallot patch on the Skagit Flats dried out enough to be worked into raised beds. The dikes on the nearby Samish River have broken several times in recent winters, flooding the area around Bow-Edison. Luckily, my field is slightly higher than the surrounding acreage, and the encircling roadbeds also help keep out the temporary lakes that cover the Samish Basin. Since then, to ensure good drainage, I rake up the freshly tilled soil into six-inch high beds, and dig a shovel-deep trench around the entire planting. The half dozen large cows and their good-sized calves in the adjacent small field always meander over to the fence line to watch what is going on next to their pasture, hoping it might provide something for them to eat. They lose interest once they smell the allium bulbs going into the soil and eventually return to munching on their rich grass.

On this sunny autumn day, my planting partners and I put in 950-plus bulbs of garlic and 100-plus of shallots. The garlic crop is entirely hard neck, mostly the Music and Deja Vu varieties, both of which grow to a good size, keep relatively well stored in paper bags in the garage, and are easy to peel in the kitchen. We also have two smaller plantings: Russian Red garlic, which lasts all winter and well into the spring months due to a vary tight, hard outer sheath; and Korean Red, a zesty, hot garlic good for kimchi and other spicy recipes. The challenge each year is to keep stored garlic usable until the very first garlic-scapes appear in late spring. I hedge my bet, processing most of the now-sprouting, end-of-winter cloves and freezing the smooth white pulp to make sure there is always fresh garlic puree available for soups, stews, or added to cooking water for grains. Small jelly jars or ice cube trays work well for freezing in usable quantities.

Shallots, however, given their thick, papery skins, will easily last all winter and even up to a full year if kept in a cool shed, laid flat on trays or loosely stored in paper bags hung up in the air. A few get moldy, but most stay firm and only need careful cleaning before chopping. In spite of their small size compared to onions, they are worth the trouble for their delicate flavor. The shallots we planted next to the garlic on the flats were from this summer’s harvest of Dutch Yellow and French Red bulbs. I also ordered two new French shallot varieties from Territorial Seed, some of which I also planted in my Fidalgo Island garden. Years ago I had to abandon growing garlic there due to the dreaded White Rot disease, which means no garlic planting for at least 12 years. I had successfully grown shallots there many years prior, so I am hoping to grow a related but different over-wintered allium at my home site. In recent years, summer onions and fresh scallions have done well. We shall see.

Smashing Pumpkins

In early June, I was watering the garlic beds for the last time before letting the maturing bulbs dry out prior to harvest in July. Next door, the farmer was plowing up a 30- acre cow pasture, using deep blades behind a large tractor. He had grown pumpkins and winter squash the year before on the other side of my garlic beds and then followed it with winter wheat. I had watched as he harvested those pumpkins just in time for the Halloween season, fork-lifting the large, square boxes of pumpkins onto a large, flatbed trailer behind a semi driven directly into the field. The cardboard boxes were decorated with large, grinning jack-o’- lantern faces: this was industrial farming at its most efficient, even if only for spooky pumpkin carving or autumnal décor by a front entrance. Food as seasonal display.

Now he was tilling up a much larger piece of ground that had been a cow pasture for many years; after discing and harrowing, he planted a new crop of pumpkins and winter squash. Given the extended warm, but not too hot, weather we had all summer this year, the field was soon covered with large green leaves and swelling globes. On the cusp of Halloween, however, I noticed the large field was still mostly covered with ripe pumpkins and mature winter squash. A single truck was being loaded with a final shipment, leaving a sea of orange on the ground, along with a few mounds of green Hubbard and cream-colored Butternut squash.

Then the large tractor appeared again, but this time to disc up all those ripe cucurbits, some 50,000 by one estimate. In years before, the yield had been 20 large bins per acre. This year, with the longer summer, and, in spite of the drier weather, the field had produced a bumper crop of 50 bins per acre. He had sold all he could, but there were still too many this late in the season, and certainly beyond the capacity of local gleaning groups. These weren’t Sugar Pie pumpkins, and the winter squash, no matter how invitingly baked with butter and maple syrup, is mostly a holiday staple these days. So, diced and chopped and smashed they were, providing at least organic matter for the soil, and acres of seeds for the flocks of crows that came to feast. And the cows next door were fed a load of chopped up pumpkins and squash, which they excitedly ran over to consume, as if they were getting Halloween candy.

Such an overly successful crop can be seen as one positive effect of our changing climate: a warmer, extended growing season, along with what must have been subirrigation from groundwater still available in August, in spite of reduced flows in the Skagit River. There were no overhead sprinklers as seen elsewhere in the valley for potatoes and other thirsty crops. Still, it was hard to watch the unplanned-for glut being plowed under. In the olden days, squash was stored in the barns under a layer of hay for family use all winter, and the cured pumpkins fed to the livestock. Even the watery flesh of jack-o’-lantern pumpkins could be made into pie, with careful straining and baking. Now, the current mania for everything pumpkin-flavored that hits the markets and pubs and coffee stands in October is supplied by commercial syrups and artificial flavorings, not by fresh chunks processed in one’s kitchen.

Winter Is Coming

Moving on: the fall, winter, and over-wintering crops are lining up like dutiful soldiers. Planted in late summer, the Romanesco Cauliflower have huge leaves, likely from the early fall rain and mild October weather, but have delayed forming their Fibonacci-patterned heads. Maybe by Thanksgiving. The January King cabbage is already starting to head up; while the Valentine Broccoli and the Cape Verde Purple Cauliflower are due to mature in midwinter. The Tokyo Cross turnip greens, free of warm weather pests, are sprouting from their woody roots; the leeks are thickening nicely; the hardy lettuces are slowly leafing out; and the Purple Sprouting Broccoli is sizing up pre-winter, preparing to make early spring flowers. My one volunteer Collard green plant is a giant circle of flat leaves that will handily survive all winter, along with the kales. And, in spite of the chilly nights, the late summer broccoli is still producing flowers, which the overwintering hummingbirds visit, in between their trips to the nearby sugar-water feeders. When in doubt, feed the birds.

______________________________

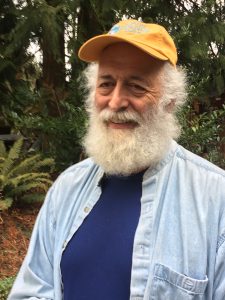

Peter Heffelfinger, a Washington State University master gardener, has gardened organically on Fidalgo Island and the Skagit Flats for over 40 years. He has given workshops in year-round gardening for Transition Fidalgo/Eat Your Yard, Christianson’s Nursery, and at the Washington State University County Extension Service. He is a Salish Sea Steward, working on the invasive green crab survey.