by Allan Richardson

This article is based on excerpts from “Nooksack Place Names: Geography, Culture, and Language,” coauthored by Allan Richardson and Brent Galloway. (1)

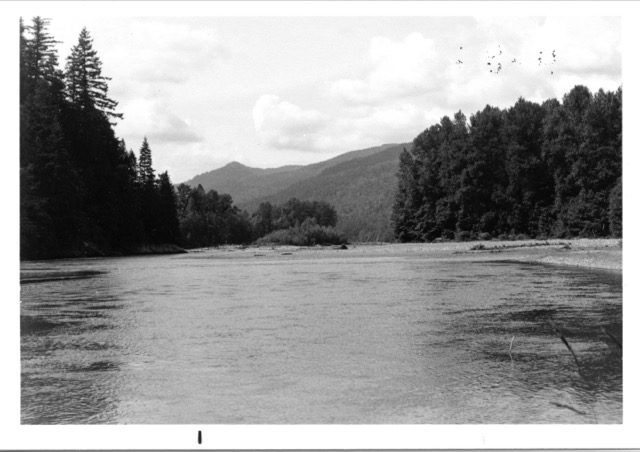

Nuxw7íyem (always clear water), South Fork Nooksack River at its mouth. Waters of the North and Middle Forks enter from the right. View to the north, down the main river. 17 July 1980. photo: B. Galloway

The Nooksack People

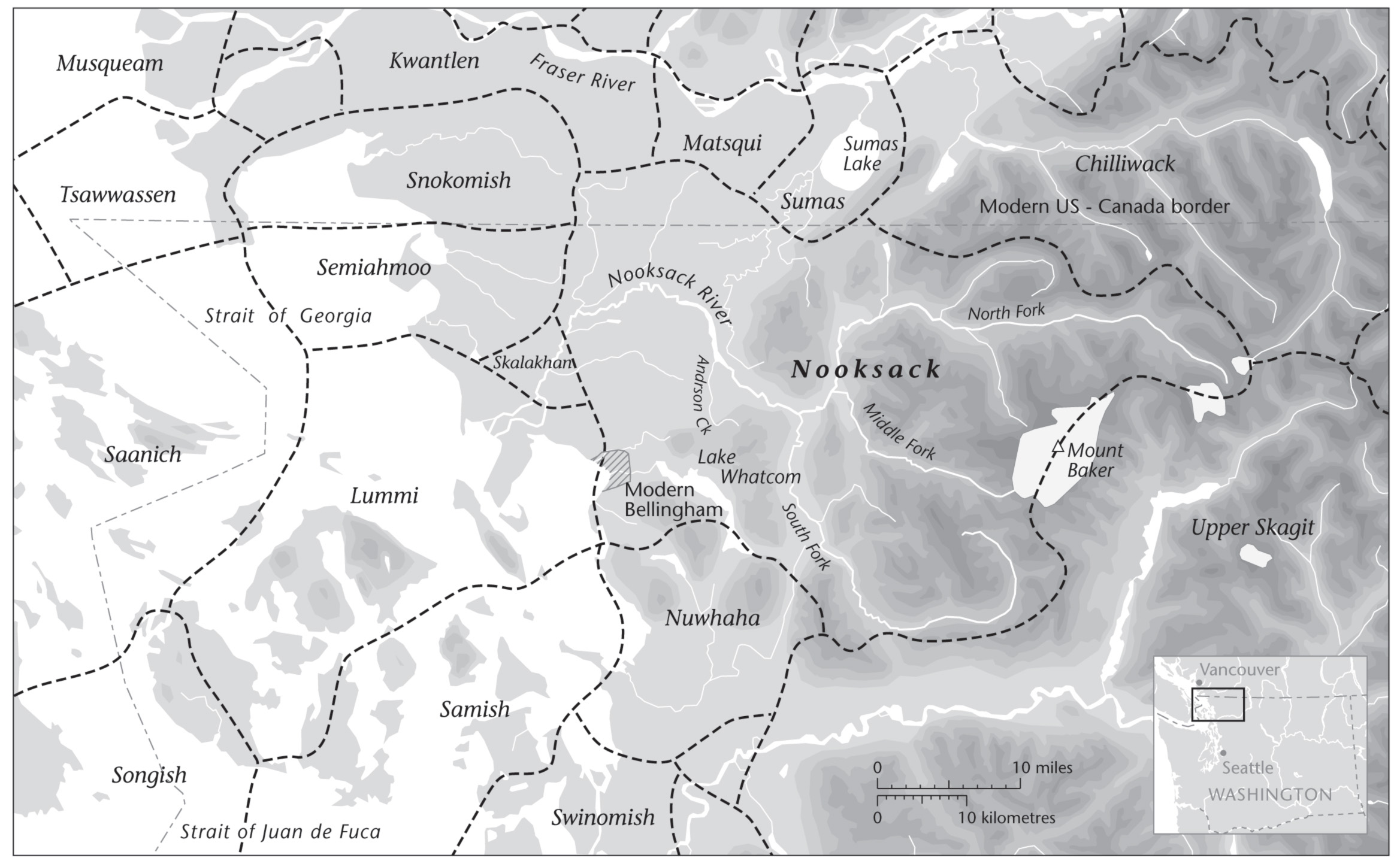

The Nooksack Indians are a Coast Salish people with a distinct Salishan language known as Nooksack, or Lhéchelesem, which in the 19th century was spoken only by them. In the early 19th century, they lived in 13 or more winter villages on or near the Nooksack River and its tributaries, the Sumas River, and Lake Whatcom. Nooksack territory extended into Skagit County to the south, into British Columbia to the north, and from Bellingham Bay in the west to the area around Mt. Baker in the east. The map shows the approximate territories of the Nooksack people and their neighbors in the early 19th century.

The Nooksack core area was the Nooksack River and its watershed from near its mouth to its headwaters surrounding Mt. Baker, plus most of the Sumas River drainage south of the present International Boundary. In this area resources were shared freely except for family ownership of root digging plots at Nuxwsá7aq, the place that gave its name to the river and the people. Non-Nooksack people could use the resources in the Nooksack core area if they shared descent from Nooksack ancestors or if they were tied to living Nooksack families by marriage.

The edges of Nooksack territory were shared with other groups: the upper North Fork, with the people of the Chilliwack area; the upper South Fork, also used by Skagit River people; and Lake Whatcom, with a mixed Nooksack and Nuwhaha (Samish River) village. All of the saltwater areas used by the Nooksack people were also used by other groups. These areas included Chuckanut Bay, Bellingham Bay, Cherry Point, Birch Bay, and Semiahmoo Spit.

Territory of the Nooksack and adjacent groups, ca. 1820. This map, by Eric Leinberger, is reprinted with permission of the publisher from “Nooksack Place Names” by Allan Richardson and Brent Galloway ©University of British Columbia Press 2011. All rights reserved by the publisher.

Today, the Nooksack people live predominantly in the same area that was their homeland in centuries past. Nooksack occupation of the area where their language was spoken in the 19th century has been continuous to the present, although the terms of occupation have changed, as can be seen in a brief historical review.

The Nooksack were one of many Indian groups that were party to the Point Elliott Treaty of 1855, in which title to the land of much of western Washington was exchanged for recognition of fishing, hunting, and gathering rights and a guarantee of certain government services. The Nooksack were expected to move to the Lummi Reservation, but few did. The Nooksack people were able to gain legal title to small portions of their traditional lands, including many of the village sites, by filing homestead claims on them.

In 1874, only the downriver Lynden and Everson areas had been surveyed, and seven homestead applications were made at this time. These first homesteads received five-year restricted patents under the provisions of an act of Congress passed in March 1875. None of these lands are in Indian ownership today, except for the two tribal cemeteries on Northwood Road. As upriver areas were surveyed, 30 additional homestead claims were filed, and trust titles were eventually granted to 3,847 acres under provisions of the Indian Homestead Act of 1884. (2) These trust homesteads included many villages and other culturally important sites. About 2,400 acres of the homestead lands remain in trust today, some held by the tribe, some by individuals, and much in complex multiple heirship.

Since the Nooksack were not granted a separate reservation in the 19th century, they were no longer recognized as a tribe by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, yet they continued to function as a tribe. In the 1950s, the tribe, under the leadership of Joe Louie, pursued a land claim case with the Indian Claims Commission (ICC), which decided in 1955 that the Nooksack were indeed a tribe of Indians whose lands had been taken without compensation, but that they only “exclusively occupied and used” a small portion of their traditional territory (Indian Claims Commission, Docket No. 46). It was further decided that the value of the lands at the time of the Point Elliott Treaty was $0.65 per acre, and that only this amount would be paid. A payment of $43,383 for 80,000 acres of the 400,000 acres claimed was provided by Congress in 1965. (3) The 400,000-acre claim approximates the Nooksack territory shown on the map.

In the 1960s, the tribe had a Community Action Program and launched an effort to gain federal recognition. In 1970, it gained title to four buildings on an acre of land; this became the Nooksack Reservation and is the location of the present tribal center. In 1973, full federal recognition was granted. The following year, the Nooksack Tribe joined the United States vs. Washington, 384 F.Supp. 312 (W.D. Wash. 1974), case as a treaty tribe with fishing rights for enrolled members. There are now about 2,000 members of the Nooksack Indian Tribe.

The Nooksack River

The Nooksack River valley from the location of today’s city of Ferndale to the headwaters in the mountains has been the homeland of the Nooksack Indians as far back as oral history extends, perhaps for thousands of years. Even so, the portion of the Nooksack River from its mouth to the forks at Nuxw7íyem above Deming apparently had no distinct name in Lhéchelesem. The Nooksack people probably used the term stólaw7, meaning river, since this was the main river (similarly people living on the Fraser River refer to their river as stó:lō in their language).

The river was recorded as “Nooksahk” or “Nooksaak River” or similar forms in early historical sources. In 1857 G. Clinton Gardner stated that above the delta channels and the first jam, “the Indians living on the river are different bands of the Nook-sahk tribe and call it the Nook-sahk river.” (4) The name Nooksack has its origins as the name of a specific place Nuxwsá7aq, Anderson Creek and the area at the mouth of Anderson Creek, with the meaning always bracken fern roots. This location is near the historic town of Goshen, west of the Mt. Baker Highway bridge. Many traditional fishing sites are located along the river and on its tributary streams, and treaty-guaranteed net fishing continues in the main stem of the Nooksack River today.

The South Fork Nooksack River and the village at its mouth were named Nuxw7íyem, always clear water, because the water is non-glacial and clear much of the year, in contrast to the other forks. The village was a large and important traditional village with longhouses on both sides of the mouth of the South Fork, the view shown in the photo. This was the major settlement of the upriver area, and the home of Xemtl’ílem, an important 19th-century Nooksack leader. The mouth of the South Fork was an important traditional weir location for catching spring Chinook and silver salmon, and has continued to be fished up to the present.

Upstream in the first canyon on the South Fork is Yúmechiy, spring salmon-place. This canyon, also known as Dye’s Canyon, is 1 3⁄4 miles above Skookum Creek. It was the most important fishing location for spring Chinook salmon, and perhaps the most important of all Nooksack fishing locations. The South Fork is very narrow here, with rocks suitable for fishing. The Middle Fork Nooksack River and the village located at its mouth were named, Nuxwt’íqw’em, always murky water, due to its turbulent glacial water.

The Middle Fork had a strong run of steelhead, but smaller runs of other salmon because of its turbulent, cloudy water. The Middle Fork was important as a route to hunting and berry-picking areas on the slopes of Mt. Baker. This route to Mt. Baker was also chosen by the Nooksack Indian guides on Edmund Coleman’s 1868 climbing expedition, which clearly documents Nooksack familiarity with the area. (5)

In recent years, the Middle Fork watershed has become the focus of traditional religious activities because it is less disturbed by modern developments than other parts of the Nooksack area. The Nooksack Tribe has gone to court to block hydroelectric projects on tributaries of the Middle Fork, and has requested that the Middle Fork watershed be formally recognized as a traditional cultural property through the National Register of Historic Places. The North Fork Nooksack River was Chuw7álich, a name of unknown meaning. This is the largest and longest of the three forks of the Nooksack River. The North Fork was the route of access to important mountain goat hunting areas on the slopes of Mt. Baker, Mt. Shuksan, and other peaks. Lower elevations or less rocky areas were also used for hunting other species and gathering berries.

The North Fork had important runs of steelhead, pink salmon, silver salmon, and especially dog salmon. The North Fork was fished from Nuxw7íyem to Nooksack Falls, primarily in jams and eddies, or at the mouths of side creeks, such as Kendall Creek.

Kendall Creek and the village at its mouth were named Xwkw’ól7oxwey, always-dog salmon-place. The creek was a major spawning ground for dog salmon, with truly massive runs. Many people came here each fall to catch and dry dog salmon. It has been described as the “biggest camping ground in the valley,” and as having “huge smoke houses,” possibly as many as four or five. There were permanent residents here early in the 19th century, but after a smallpox epidemic in the 1830s or 1840s, the site was abandoned except for seasonal use. The site of Xwkw’ól7oxwey village is now occupied by the Washington State Salmon Hatchery, which has greatly modified the creek mouth area. The last Indian smokehouse, which was standing around 1905, was probably located near the old hatchery buildings, just east of the present creek channel. (6)

This has been a brief summary of the relationship of the indigenous Nooksack people to their homeland and the resources found there, with a focus on their strong connection to the Nooksack River. An expanded view can be found in “Nooksack Place Names: Geography, Culture, and Language,” available in Bellingham and Whatcom County libraries, as well as in local bookstores.

Endnotes

1. Richardson, A. & Galloway, B. (2011). “Nooksack Place Names: Geography, Culture, and Language,” Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press.

2. Richardson, A. (1979). “Longhouses to Homesteads: Nooksack Indian Settlement, 1820-1895.” American Indian Journal 5, no.8 (August): 8-12.

3. Richardson, A. & Galloway, B. (2011). “Nooksack Place Names: Geography, Culture, and Language,” Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, page 22.

4. Gardner, G. C. (1857). “Report of G. Clinton Gardner, Assistant Astronomer and Surveyor, of Reconnaissance of Country East of Camp Semiahmoo, Dated Sept. 3, 1857.” Unpublished field report of the United States Northwest Boundary Survey, U.S. National Archives, RG 76, E 196.

5. Coleman, E. (1869). “Mountaineering on the Pacific in 1868.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 39: 793-817.

6. Richardson, A. & Galloway, B. (2011). “Nooksack Place Names: Geography, Culture, and Language,” Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, pages 134-136.

__________________________________

Allan Richardson received an M.A. in Anthropology from the University of Washington, Seattle, and taught Anthropology at Whatcom Community College for 38 years. He has published articles on Northwest Coast native culture and has served as consultant to the Nooksack Indian Tribe for a number of grants and legal cases. Mr. Richardson is coauthor with Dr. Brent Galloway of the book “Nooksack Place Names: Geography, Culture, and Language” (UBC Press, 2011). He is also active in the Washington Native Plant Society, and lives on a small farm on the outskirts of Bellingham, Washington.