by Ron Kleinknecht

Part 4

In Parts 1, 2 and 3 of this series (1,2,3), I described the Nooksack River, some of its history, and the degradation of its habitats and waters. I also described how this degradation has imperiled native salmon that have spawned, grown, gone to sea and returned to the river. Salmon as a keystone species affects and is affected by all parts of the river and its watershed. Further, salmon represent a cultural icon to the native tribes, is a source of their subsistence, and is a large commercial industry in the Northwest. Moreover, it is the primary food source of our southern resident orca. There is strong consensus that the salmon must be saved.

This last part addresses some more of the monumental efforts that are being put forth to save the salmon. As noted previously, these efforts are not easy and they take dedication and cooperation among numerous individuals and groups who are stakeholders in their welfare. Here I focus first on the interplay and cooperation of our county’s farmers and conservationists.

Certain agricultural practices are incompatible with keeping a river habitable for fish and other aquatic critters. That is, unless significant steps are taken to reduce or eliminate farm pollution, such as runoff and seepage of fertilizers and animal manure, the river is unlikely to be saved for the salmon. This runoff has been a significant problem for the Nooksack River, including its three forks and their tributaries as well as for the shellfish tidelands into which the river empties.

This situation has created a conflict over the years between farmers and environmentalists, tribes and commercial fishers, all intent on saving the salmon. A dairy farmer told me recently that she has experienced slogans directed toward her such as “Cows Kill Salmon.” That conflict seems to be abating somewhat as we are seeing increasing examples of simple cooperation between the sides, and, as I describe, modern farm waste processing technology is being introduced.

Farming Technology

The numerous small creeks that drain the hills and lower lands into the Nooksack and the bay are a common geological feature throughout the county. Most of these streams are historical salmon spawning streams, such as Double Ditch and Fish Trap creeks. Most of these have been straightened, dredged, swamped, and blocked in the process of building roads and developing the land for agriculture.

Since these creeks run through and by fields where their riparian habitats are compromised, they collect runoff water from roads and farms that then drains into the Nooksack and ultimately into the Salish Sea. The riparian areas along the streams have been largely denuded of native trees and shrubs that naturally shaded the water and diminished runoff. Now non-native reed canarygrass grows right down to the water’s edge. (4) Although reed canarygrass is also a forage resource for livestock, it is ultimately harmful to natural habitats as it crowds out native vegetation.

Runoff and seepage from livestock manure (waste products) and farm fertilizer are a couple of the farming sources of river pollution. Controlling this runoff from entering creeks and the river would go a long way toward returning the Nooksack to its previous level of salmon-friendly waters and cleaning up the bay and its shellfish beds. Numerous efforts are currently in operation to stem the flow of such waste products.

One relatively bright spot for the future of fish stream restoration and maintenance comes from technology applied to dairy farming, an industry that has traditionally been one of greatest polluters of waterways, estuaries and tidelands. This technology, along with some farmers’ cooperation, can lead to the rescue of the Nooksack’s manure runoff and seepage ills.

I recently took a tour of a family farm that has installed state-of-the-art technology at their dairy farm along the South Fork of the Nooksack. (Although the application of this technology is new and revolutionary here, it is mandated for many dairy farms in Western Europe.)

The technology involves anaerobic digesters that transform farm waste (manure) into reusable resources that go back into the farm and do not become harmful runoff. This equipment was purchased in part with assistance from a grant from the Washington State Conservation Commission to demonstrate its economic feasibility. (5)

Coldstream Farms is the first farm in the state to use this full process. The cows’ manure from their feeding sheds is piped into a holding pond from which it is fed into a digester or “BeddingMaster” filtration process which turns the solid content into sterilized reusable products, such as bedding for the cows and solid fertilizer for their hay crops. Finally, the residual liquid is filtered into relatively pure water that can be used for farm cleanup and eventually, when certified, the excess could be pumped back into the river at critical times of low stream flow. (6).

Result of a filtration process to produce a soft fluffy substance that becomes bedding material for the dairy cows. photo: Ron Kleinknecht

From there, other filtration processes (nanofiltration and reverse osmosis) continue to produce useable products as shown in the photo of jars.

From the BeddingMaster, the leftover liquid, as seen in the left jar, is a mucky liquid. An emulsifier is then introduced that separates most of solids from the liquid as seen in the second jar from the left. The solids from this become the pile of brown material in the center, which is a solid fertilizer rich in nitrogen and phosphorous and can be used or sold to other farmers. The remaining liquid in the third jar can also be used as fertilizer to be spread on the fields or put through a final process of nanofiltration that completely purifies the liquid into reusable water — the jar on the right. photo: Ron Kleinknect

Technology is now clearly present to nearly eliminate farm animal waste as a river pollutant. What is left is to demonstrate its economic viability and/or incentives for more farmers to adopt this technology.

The field that surrounds the farm is fertilized by the product of the manure. photo: Ron Kleinknecht

Programs and Resources

One mediator in this “farm — environmental” controversy is the Whatcom Conservation District (WCD). (7) And perhaps they are an unsung hero in the issue melding farming and land usage with best practices for environmental stewardship. This largely grant-funded program with some state support assists farmers and landowners in using best practices for their property and farms to sustain the lands, improve water quality and habitat for fish and wildlife, and reduce soil erosion.

Although not the same level of technology, other data-based approaches are being used to reduce animal waste runoff and seepage. In cooperation with WSU Extension services, the WCD provides information and guidelines to farmers for ecologically sound use of manure as fertilizer on farmland to minimize runoff and pollution. (8)

Among the services provided are testing manure for nutrients and pollutants, recommended application rate, and an online interactive map showing current setback recommendations for how close to waterways manure can be spread to minimize runoff, depending on season and rain. They will even loan their manure spreader. (9)

These practices directly counter many of the very things I noted in Part 2 that has led to degradation of the Nooksack and Portage Bay waters. WCD’s job is to reverse that process by working with farmers, and, so far, they have had over 435 county land owners participate in their programs, and they have planted more than 2,800 acres with buffers to streams, wetlands, and ditches on county property. (7)

To assist in cleaning up the pollution in the Nooksack, Whatcom County created the Portage Bay Shellfish Protection District and advisory committee in 1998 as a joint commission of farmers and tribes working to reduce pollution that closes the shellfish beds/lands in Bellingham and Portage bays. Although these services and assistance have been in force for some years, their ultimate effectiveness has been questioned as the river and Portage Bay have continued to be polluted for much of the year. A recent development, however, gives hope that these efforts might be paying off.

One sign of the state of the Nooksack’s water quality is the amount of fecal coliform bacteria from both animal and human waste found in shellfish in and around Portage Bay on the Lummi reservation where the river empties. The state Department of Health has recently declared the bay open for shellfish harvest for nine months of the year as opposed to six or fewer months as has been the case in recent years. (10) Hats off to the many agencies noted in Part 3, and specifically the Lummi tribal council, Whatcom Family Farmers, WCD staff and the many others who contributed this undertaking. Although it remains a work in progress, it is a cooperative success story in the making

Although there is a considerable way to go to restore the river and bay to their historic states, as noted, progress is happening. Most notably, this progress only developed when all stakeholders pitched in to do their parts and assist each other. Another recent example of such cooperation happened this past summer.

Two of the county’s many creeks, Double Ditch and Fish Trap, still support two endangered species of steelhead trout and Chinook salmon, along with the five other salmon species. Double Ditch Creek is split into two branches, one on either side of the road and both enter the county from the north across the border. Just this past summer, a beaver dam north of the border blocked the flow of one branch of Double Ditch, killing thousands of small fry salmon and trout and threatening to kill them all. (11)

This crisis was spotted by local dairy farmers who alerted the Department of Fish and Wildlife officials. The WDFW officials told the farmers that if the fish could get some cool water they could last until biologists could get there to deal with the problem. The farmers switched their crop watering irrigation pumps from their lands to the ditch until the following day. When the biologists arrived, they netted the salmon in the low-water ditch and moved them across the road into the other ditch that has sufficient water, saving those fish that remained.

Although this is a good sign of the willingness to work together to save the fish, the fact remains that these ditches run through and by dairy farms and berry fields and carry their runoff to the river and on to the bay. The measures described above to reduce manure-based pollution should contribute to the solution but clearly more will be needed.

What Else Can Be Done?

One other seemingly obvious route to bringing the fish back is to raise more fish in hatcheries and release them into the ocean as our state has been doing for over 100 years. (12) Although this sounds like a logical solution, it is actually quite controversial. (13)

Washington state has been rearing salmon by the many millions each year and releasing them into the river, where they head to the sea for several years before they return to spawn. For example, in 2013, 73 million salmon were released by the State of Washington hatcheries and now it is probably closer to 100 million. Even more will be released this year in an effort to provide more fish for the resident orca.

At this point, the numbers of hatchery fish far exceed the native or wild fish, as 75 percent of salmon caught in Puget Sound are hatchery raised. There are now about 66 state-run salmon hatcheries and 51 tribal hatcheries in the state. After putting all of these fish into the salt water, the overall salmon runs are still not increasing. And worse, the hatchery fish might even be harming the native, wild salmon. (14)

There is much more to saving the salmon than putting more of them into the water and improving their habitat, although both are critically important. Other issues are afoot as illustrated by the fact that the percentage of released salmon that return has dropped to just 1 in 100 from 3 per 100 40 years ago. Many factors likely contribute to this decline, such as warmer ocean temperatures, more predators in their estuaries and at sea. It is believed that hatchery fish might not be as hardy as the wild fish, and interbreeding can weaken the wild salmon stock. (14)

All of this is not say that there are no more fish here. In some runs, there are lots and many come back to spawn at the hatchery waters from which they were released. However, there are fewer wild salmon and hatcheries might not be their final solution.

Any final and successful solution to restoring salmon must contain two major thrusts: 1) restore lost habitats, and 2) curtail ongoing pollution and degradation of the land and water. In this and the previous article, I have illustrated some of the efforts directed to both of these categories.

One of the major stakeholders in our salmon stocks along the river and for all of Puget Sound and the Salish Sea are the Treaty Indian Tribes of Western Washington. They note, as have others that over past 40 years, much money has been spent, habitat restored, cuts made to fishing harvest along with increases in hatcheries output and still the numbers of fish go down. These groups have recently announced that they will institute their own strategy they call: “Gwadzadad” in Lushootseed language, (a Puget Sound/Salish language group spoken by of Northwest Indians), meaning “the teachings of our ancestors.”

“It is a unified tribal habitat strategy designed to organize and focus work around key habitats and shared goals necessary to protect tribal treaty rights and resources. It aims to preserve and restore the natural functions and connectivity of our river, marine and upland ecosystems, and to seek accountability for decisions on the use of our lands and waters.” (15)

The very people whose lives, livelihoods and culture depend on these resources are working hard to return the salmon, but, like many others close to the problem, they are seriously concerned about the outcome.

Beyond Habitat and Hatcheries

As described in these articles, progress is being made with restoring streamside vegetation, opening up streams by removing culverts, and reducing polluting farming practices. Hatcheries raise and release millions of salmon each year. Even if we largely reestablish the habitats for salmon to spawn, grow, and return, the fact remains that the largest part of their life cycle is spent in the ocean where conditions are not always favorable. Only one of a salmon’s two to four years is spent in these streams before they head to sea.

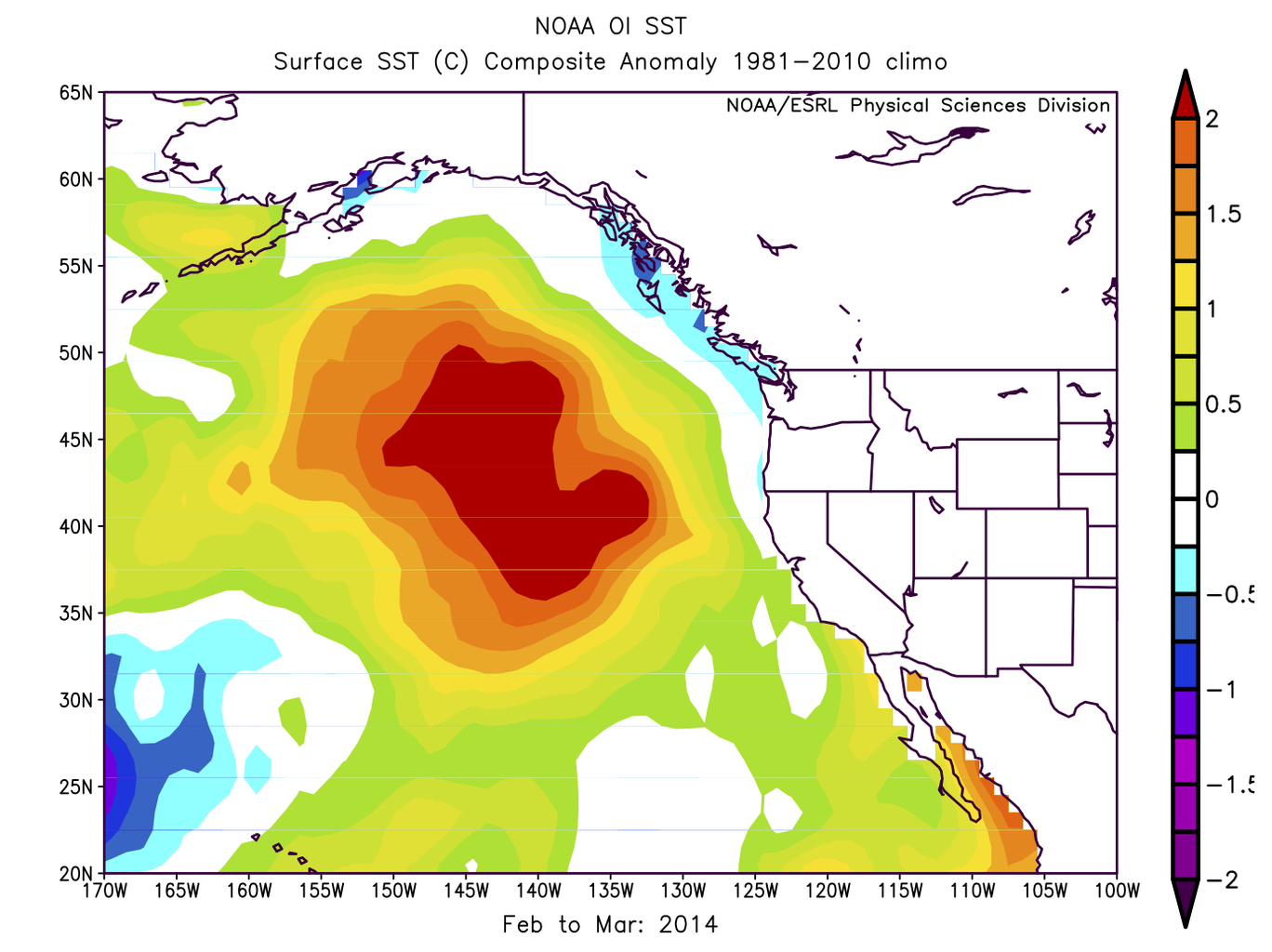

Among the obstacles to salmon’s future success that go beyond the local habitat are ocean warming and “The Blob,” which are beyond our immediate control. In late 2013, a large mass of warm water dubbed The Blob, appeared over the North Pacific and Gulf of Alaska and persisted into 2016. This warmed water area is where the salmon congregate for a couple of years as they mature and feed before they return to their natal streams to spawn.

This temperature anomaly has affected zooplankton, the stuff that salmon feed and grow on, in the North Pacific. There were lasting effects of The Blob on the recent salmon returns. Until a few months ago, we were hopeful that it was gone for good. But recently, it has reared its ugly head again as “Son of the Blob.” How long this one will last is unknown, as is its effect on salmon returns in the coming years. Scientists have suggested that The Blob might become the new normal. (16, 17)

A final factor I’ll mention that affects our salmon beyond the river and streams is that the seal and sea lion population eat 22 percent of smolts (young salmon preparing to go to sea) before they even get out of Puget Sound. Prior to the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, fishermen shot these mammals on sight. Following their protection 47 years ago, the Puget Sound seal population has grown to become one of the densest in the world. (18)

Highlighting this factor in salmon recovery efforts is that scientists have found an inverse correlation between seal density and the productivity of Chinook salmon in the Pacific Northwest. (19). That is, more seals predict fewer salmon returns.

One solution is clear but problematic. For example, California sea lion predation on salmon in the Columbia River is said to be decimating the Chinook runs up the Columbia and Snake rivers. The sea lions congregate at the base of the Columbia River dams where the salmon congregate before climbing the fish ladders and heading up river to spawn. They are easy pickings. Recently, the National Marine Fisheries Service has been authorized to conduct some selective killing of up to 92 of these animals per year along the Columbia River dams. (20)

Future of Salmon and the Nooksack

Based on the efforts illustrated in these four articles, along with others in Whatcom Watch, there are some clear bright spots that give reason for hope. Should we be optimistic? My optimism is buoyed by the numbers of people and agencies that take this problem seriously and devote their time and money to fixing it. Our state Legislature has recently allocated $6.2 million to address the problems of habitat loss and diminished salmon to feed us and the orca. (21)

However, my optimism is tempered by the large-scale barriers, many of which seem to be beyond our immediate local control, such as the increasing effects of climate change and The Blob, which are already affecting our watersheds and salmon.

The warm water anomaly in the North Pacific dubbed “The Blob” by Washington state climatologist Nick Bond. In late 2013, a large mass of warm water dubbed The Blob appeared over the North Pacific and Gulf of Alaska and persisted into 2016. This warmed water area is where the salmon congregate for a couple of years as they mature. This temperature anomaly has affected zooplankton, the stuff that salmon feed and grow on in the North Pacific.

My view is similar to that expressed by retired biologist David Beatty in a recent Bellingham Herald article (22):

“Overall, Puget Sound is not improving,” Beatty said.

Asked if he was optimistic that salmon recovery efforts will succeed, Beatty replied, “Yes, one should be optimistic if the human element can get it together, but that hasn’t completely happened. Unless we have that, no — you can’t be optimistic.”

I would add a similar sentiment, but include climate change. If humankind can get it together to slow climate change, in addition to tackling our more local environmental issues, including pollution and habitat loss, we might have a chance.

In summary, if we have the will to provide the needed time and money, we can go a long way to saving the salmon and the orca with cooperative effort at all levels. There is good news in that the current Legislature has allocated money to release more salmon to feed the orca and to restore the natural functions of the state’s rivers and floodplains. (21) They also allocated some (but not all) funding for the court-mandated removal of culverts discussed in the May issue of Whatcom Watch. (3) So, there is some continuing movement at the state level, which is encouraging.

At the same time, global factors such as climate warming insert their ugly heads and may counter our best efforts. If the ocean is too warm, and, if the glaciers’ icy waters retreat, it will be difficult for the fish to flourish and survive, no matter how many culverts we replace. If the streams run too low and are too warm, the trees we plant along the shore will be too little to cool the waters.

I am moderately optimistic about our local efforts on the Nooksack and its tributary creeks throughout the county. Given time, I believe that we can continue to make good progress toward saving the salmon and their habitat. We must continue to do what we can locally and hope that others are doing all they can for the many other streams and rivers that feed the Salish Sea. At the same time, we must also support national and international work to combat our self-induced heating of our planet.

I hope to see you at some of the many volunteer work parties around the county restoring our natural legacy and ensuring its future for generations to come.

References

1. Whatcom Watch, March 2019

4. https://www.nwcb.wa.gov/weeds/reed-canarygrass

5. https://www.pudwhatcom.org/pud-partners-with-coldstream-farms-dairy-to-produce-clean-water/

8. http://cru.cahe.wsu.edu/CEPublications/pnw533/pnw533.pdf

9. https://www.whatcomcd.org/msa

10. https://www.whatcomcd.org/node/297

11. https://www.bellinghamherald.com/news/local/article216618980.html

12. https://stateofsalmon.wa.gov/

13. http://www.wildfishconservancy.org/resources/science-library/wild-vs.-hatchery

15. https://nwtreatytribes.org/habitat-recovery-strategy/

16. https://cliffmass.blogspot.com/2018/10/the-son-of-blob-is-back.html

19. https://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/10.1139/cjfas-2017-0481#.W0TIcdJKjIU

20. https://www.bellinghamherald.com/news/business/national-business/article229991899.html

21. https://www.bellinghamherald.com/news/local/article229880814.html

22. https://www.bellinghamherald.com/news/local/article171852652.html

_____________________________________

Ron Kleinknecht is professor emeritus of psychology and dean emeritus of Western Washington University’s College of Humanities and Social Sciences. He’s a lifelong nature and conservation enthusiast who writes about the Pacific Northwest and is a volunteer land steward for the Whatcom Land Trust.

Among the obstacles to salmon’s future success that go beyond the local habitat are ocean warming and The Blob. In late 2013, a large mass of warm water dubbed The Blob appeared over the North Pacific and Gulf of Alaska and persisted into 2016. This warmed water area is where the salmon congregate for a couple of years as they mature. This temperature anomaly has affected zooplankton, the stuff that salmon feed and grow on in the North Pacific.