by Nate Sanford

Two large mounds of dredged sediment have become the Cornwall Avenue Landfill’s most distinctive feature. Located on the northeastern shoreline of Bellingham Bay, the site is on track to become an expansive waterfront park. The Alger Learning Center and Independence High School is at the south end of Cornwall Avenue. The former St. Joseph’s Hospital, now the South Hill Apartments is east of the mounds.

courtesy photo: Port of Bellingham

In 1992, a person walking along the water on Cornwall Beach (located at the south end of Cornwall Avenue in Bellingham) made a startling discovery: glass blood vials, plastic syringes and other medical refuse. The subsequent investigation by the Department of Ecology revealed that the medical waste was just the tip of the iceberg.

More than a century of toxic refuse from the city of Bellingham and local industries had turned the Cornwall Beach site into a serious environmental hazard. The site, called the Cornwall Avenue Landfill, was identified as requiring remedial action under the Model Toxics Control Act, beginning a decades-long cleanup process that, should everything go according to plan, will reach its long-awaited conclusion in the form of a public park.

The 16.5-acre Cornwall Avenue Landfill is one of 12 environmental cleanup sites located along Bellingham Bay. Instead of removing the sediment waste at the site, the city has opted to cover it with a multilayered cap intended to isolate the contaminants, which include dioxins and furans dredged from the Squalicum Outer Harbor.

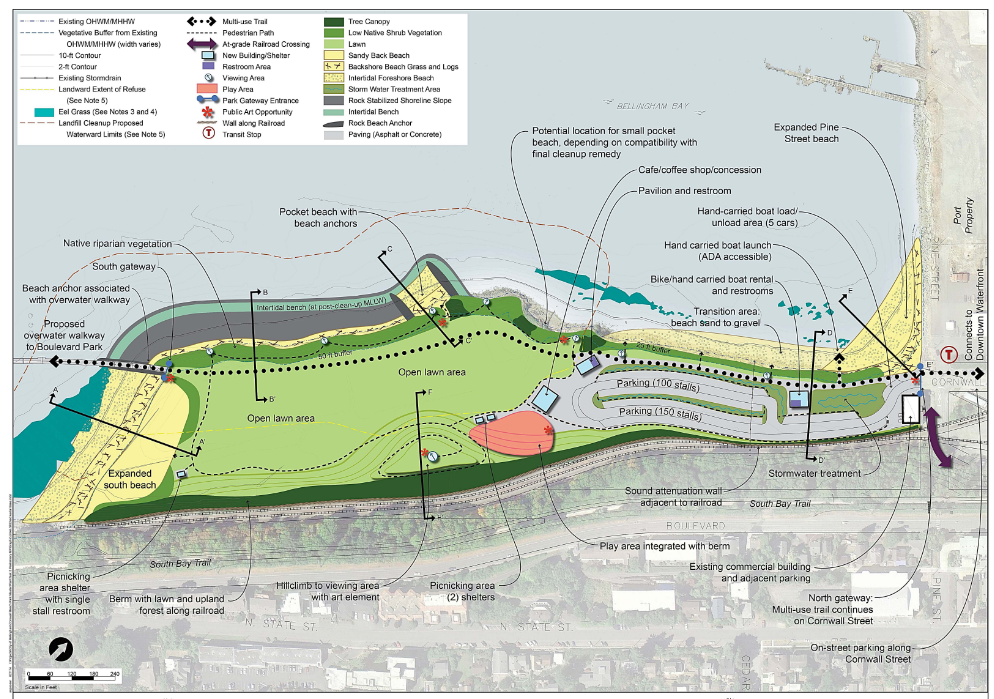

This 2014 conceptual design map of the park calls for a boat launch area, picnic space, beach access, a coffee shop and a parking lot for 250 vehicles. The actual park may be different from the conceptual design.

When the Cornwall Beach Park is completed, it will cover both the Cornwall Avenue Landfill and parts of the adjacent (to the north) R.G. Haley International Corporation, Inc. site (R.G. Haley), which is undergoing similar remediation efforts. According to the Department of Ecology’s Public Involvement Coordinator Ian Fawley, there is still not a clear timeline for cleanup construction. Because of contaminant overlap between the two sites, remediation will need to occur simultaneously.

The engineering design report for R.G. Haley has been submitted, but is still awaiting approval from the Department of Ecology, said Craig Mueller, project engineer for the city’s Public Works Department. Mueller said that, while there is a chance construction could begin by the end of 2021, a 2022 start date is more likely. When construction does begin, Mueller said it will take roughly two years to complete.

First Contamination Layer

Prior to European occupation, what is now known as the Cornwall Avenue Landfill was made up of tideflats and subtidal areas and was used by members of the Lummi Nation for commercial, ceremonial and subsistence harvesting of salmon and shellfish. The first layers of contamination were placed there in 1888 when — in violation of Lummi treaty rights — local sawmill operations began using the site for log storage and wood debris disposal.

This continued up until 1946, when the city of Bellingham purchased the site and began using it as a landfill for municipal waste. The landfill was closed in 1965 and covered by a layer of soil. Ownership was later transferred over to Georgia-Pacific, who used it for more log storage and warehousing operations. In 2005, the port repurchased the property and later transferred ownership to the city of Bellingham.

The decades of industrial and municipal use presented a number of concerns. A remedial investigation conducted by Ecology identified numerous contaminants in both the groundwater and sediment, as well as contamination of the R.G. Haley site.

The historical use of the site isn’t the only source of contamination. If you look at the Cornwall Avenue Landfill site today, you’ll see two large white mountains. They’re made up of sediment dredged from the Squalicum Outer Harbor, held in place by a white tarp and sandbags. The sediment, which is contaminated with dioxins and furans, was dumped on the site in 2011 to prevent groundwater from leaching into the landfill.

At the time, the port was in the process of dredging Squalicum Outer Harbor, two miles away. In the past, the port had been able to simply dump the dredged material in the water. But in 2010, the Army Corps of Engineers updated its regulations and suddenly the dredged sediment was too toxic for open water disposal. Instead of dumping the sediment in the water as it had always done, the city would have to find a place on land to move the sediment — an extremely costly process that could significantly delay the project.

Minor Controversy

The port looked to the still uncovered Cornwall Avenue Landfill and saw an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone. In December 2011, the port mixed the 47,500 cubic meters of Squalicum Harbor sediment with stabilizing cement and dumped it on top of the Cornwall landfill. Beneath the sediment, a separate gas collection layer was installed to gather and vent landfill gas. A white tarp was placed over the sediment to prevent exposure to the contaminants. The piles of sediment fast became a source of contention, and caused a minor controversy when several children were photographed playing on them.

Larry Altose, DOE communications manager, reported that, in April, the northeastern part of the synthetic cover over the Cornwall Avenue Landfill was damaged by windstorms and plant roots. The Port of Bellingham completed repairs in late October. While they were repairing this, the southern part of the cover was damaged in a strong windstorm. The port has a contract with a contractor to repair the damage and is working to repair it by the end of November, so it’s protected for as much of the rain and storm season as possible. Altose said it’s the first time the covers have needed to be repaired since they were installed several years ago.

When it comes to contaminated sites like the Cornwall landfill, there are generally several cleanup options. One would be complete removal, where the contaminated material is removed entirely and transported to a licensed solid waste disposal site. The common alternative to removal is capping — leaving the contaminated material in place, but covering it with several layers in an attempt to contain it.

Both options were considered for the Cornwall Avenue Landfill site. Removal was ranked highest for protecting human health, permanence, long-term effectiveness, net environmental benefit, and consideration of public concerns. But there was a problem with money. Removing all of the contaminated waste from the Cornwall site is expensive — almost 700 percent more expensive than simply covering it. In 2014, Ecology chose the cap.

North Sound Baykeeper Elenor Hines was studying environmental toxicology at Western Washington University at the time. “I remember being really upset initially, like, ‘what? They aren’t going to remove all the contaminants? They’re just going to leave them and keep them, why would they do that?’” Hines said.

But Hines said she eventually came to understand that complete removal can also come with its own drawbacks. Transporting an estimated 500,000 cubic yards of refuse and contaminated sediment by truck would create significant emissions and carry the risk of spilling the material. And even if it was safely removed, it would still have to go somewhere.

“If it’s not in our backyard, it’s just going to somebody else’s backyard,” Hines said.

Public Comments

When the Engineering Design Report was submitted for public comments in 2018, a number of people took issue with Ecology’s decision not to remove the contaminated material.

“And you are actually thinking of putting a park for children to play on top of!!!!!! No way! This toxic waste needs to be removed, relocated and cleaned & stored in a proper toxic waste collection site!!!!” said one local resident.

“A ‘capped’ cover up is in no way okay or safe for this area. Let’s learn from our past mistakes and do the job right the first time,” said another.

In response to these comments, Ecology said the four layers of the upland cap will be sufficient in protecting park users from exposure, and that the cap’s integrity will be ensured by five-year periodic reviews.

Mueller said that he has been involved in environmental engineering for over 20 years, and that capping is a very conventional strategy. Caps prevent rainwater from percolating through the waste, and act as a physical barrier for the people on top, Mueller said.

So, while the contaminated material will remain in Bellingham’s backyard for perpetuity, it will be buried beneath several layers. The contaminated sediment that was placed on top of the landfill in 2011 will be compacted into a minimum two-foot-thick low permeability soil layer and isolated from park users with a low permeability geomembrane, a geotextile drainage layer and then cover soil. On top of that will be a layer of topsoil or pavement. And one day, on top of everything: humans enjoying a day at the park.

But while the many layers may effectively isolate the contaminants below, there are still a number of environmental and human factors that could compromise the cap.

“Maybe a cap could get ruptured, or holes could get poked in it, or it might break down quicker than anticipated. That would mean that the contaminants that it was meant to hold back and maintain would have the ability to leach out into the environment and come into contact with humans,” said Hines.

Humans digging in the park, boats running aground or dropping anchor, tree roots, storm surges and the later construction of new buildings are a few of the things that could potentially cause a cap puncture. To prevent this, the final park operations plan will declare restrictions on potentially damaging activities.

Leaking Into Bellingham Bay?

A portion of the Cornwall Avenue Landfill site also extends into the water. The current engineering design report calls for that section of the site to be covered with a thin-layer sediment cap to prevent contaminants from leaking into Bellingham Bay. In response to public comments, Ecology said that in-water signage and a “no anchoring zone” will likely be established to prevent boats from damaging the cap.

More unavoidable events like earthquakes and tsunamis were also considered in the cleanup planning process, though the report acknowledges that some damage would be unavoidable. The original construction plans for the Cornwall site were designed with a 28-inch sea level rise in mind. In June 2020, the Bellingham City Council approved funding to update the design for a projected 50-inch sea level rise.

When finished, the sprawling Cornwall Beach Park will include beach access, space for hand-carried boat launching and other recreation facilities. The park, which is estimated to cost around $12.5 million, is still a long way from being finished

“But once it’s all done, it is going to be an absolutely beautiful park that has the potential to become the gem of the park system in Bellingham,” said Mueller.

Model Toxics Control Act

Initiative 97 (Hazardous Waste Cleanup Program) was on the 1988 general election ballot. The Legislature passed a less stringent alternative to the measure titled 97B. Initiative 97 passed with 85 percent of the vote and the more stringent measure passed with 56 percent of the vote. The law is partially funded by a 7/10 of 1 percent tax on hazardous substances. The funds are used to investigate, clean up, and prevent sites that are contaminated by hazardous substances.

In 1988, there were more than 13,000 known or suspected contaminated sites in Washington. More than 7,000 of these sites have been cleaned up or require no further action. The Toxics Cleanup Program is one of several programs that receive funds from the Model Toxics Control Act.

The Toxics Cleanup Program has primary responsibility for implementing and enforcing MTCA. They develop MTCA’s rules, policies, and guidance, and oversee or manage most of the cleanups in Washington. They also manage a grant program that helps local governments clean up contaminated sites in their communities so they can put abandoned properties back into use.

The Model Toxics Control Act has been amended by the Legislature 23 times (most recently in 2013), but its key principles remain in place today:

• Polluter pays

• Cleanups should be as permanent as possible

• Public participation is crucial

• Processes should demonstrate a bias toward action, permanence, and innovation

_________________________

Nate Sanford is a journalism student at Western Washington University and a story editor for The Planet Magazine. You can follow his work on twitter @sanford_nate.