How to facilitate and avoid the pitfalls of the clean car transition

by Stevan Harrell and Ray Kamada

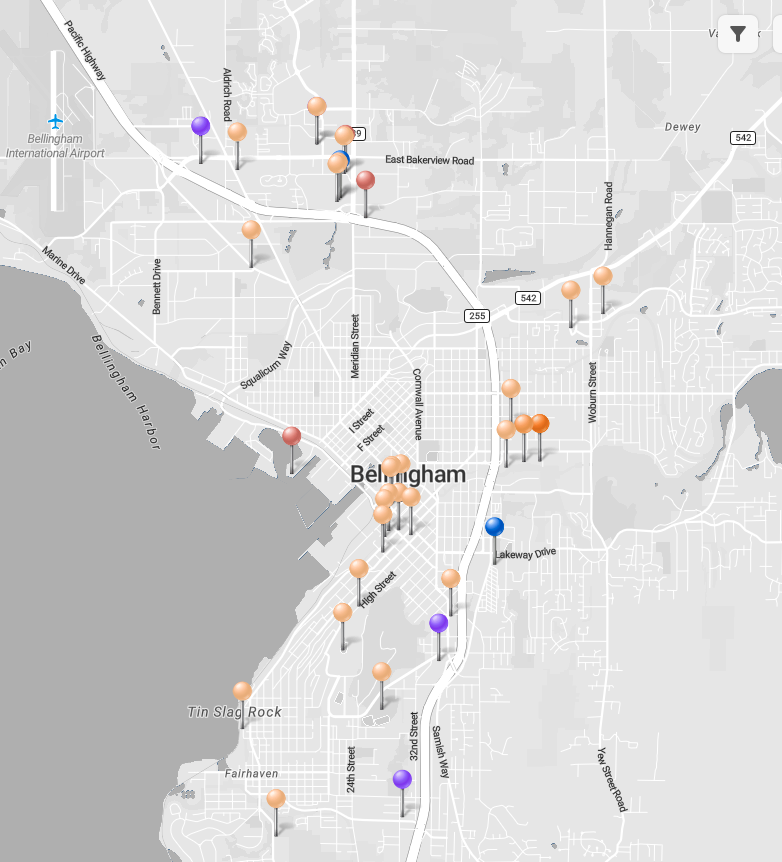

Map of Bellingham electric vehicle charging stations – March 2023. See legend at https://chargefinder.com/us/bellingham/charging-station/n73w66.

courtesy: City of Bellingham

Climate change is here. The world must reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, and fast. In the United States, where people get around mainly by car, transportation accounts for 27 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. (1) According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 13 percent of total national emissions come from cars and light trucks (2), the vehicles we use to go to work, do our jobs, go shopping, take kids to school, and go on road trips. (3) Driving cars and pickups does more to warm the earth than agriculture, aviation, home heating, or commercial activity.

However, converting our transportation system from petroleum to electricity is a novel project, and we don’t know exactly how the transition will work. We need to act fast, but flexibly, planning wisely so that we neither miss current opportunities nor lock ourselves into plans that might be outmoded in a few years. Here we outline some measures that local stakeholders could take immediately, while emphasizing that we need to stay flexible in the face of rapid change.

Here in Whatcom County, we have a special situation. We emit a lot more greenhouse gas per capita because our two refineries account for almost half of our total emissions. (4) Of the remaining half, transportation — again, mostly cars, SUVs, and pickups — accounts for 28 percent. With our population still growing, reducing emissions from transportation needs to be an important part of our climate action.

In Manhattan or San Francisco, it’s easy to get around by subway, light rail, bus, and on foot. But here in Whatcom County, it’s more difficult. Buses don’t go everywhere, and most don’t run at night. Bike trails and walking paths are great, but many of us don’t live within easy walking or biking distance of stores, schools, or workplaces. While it’s a noble goal to reduce car traffic, there are good reasons why we can’t reduce it much. About 92 percent of Whatcomites who work outside the home commute by car. (5) Few of them would bike or bus to work in the dead of winter when they have kids and groceries to pick up, even if they had easy access to trails safe from vehicle-pedestrian collisions, or even if buses ran more routes and more frequently. We can and should expand non-car ways to get around, but it won’t be nearly enough to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions as much as we need to.

In these circumstances, the best way to reduce our transportation emissions is to make it easier for people to buy, drive, and charge electric cars and light trucks (electric vehicles, or EVs for short). Until now, EVs have mostly been limited to affluent and comfortably middle-class people. When it came out in 2017, Tesla’s Model 3, its lowest priced car at $35,000, still cost quite a bit more than a Kia or Honda ICEV (internal combustion engine vehicle), even with federal subsidies (6), and even more economical EVs like the Nissan Leaf still strained working-class pocketbooks. Besides, EVs were so new, and early adopters so fond of them that there was almost no used-EV market, and electric pickups were nonexistent.

EVs — More Accessible and Affordable

This is all changing fast. Market analysts now project that, with new subsidies from the federal Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the average price of EVs will soon equal that of ICEVs, and more economical new EVs, such as the Chevy Bolt or Nissan Leaf, selling at $26,000-$28,000, or under $20,000 after the $7,500 federal Clean Vehicle Credit, will be comparable in price to new ICEVs. (7) A used-EV market is developing (8) that the IRA provides new incentives for, and EV pickups are increasingly available, though currently far more expensive than your average economy pickup. (9)

Once you have an EV, it is much cheaper to run than an ICEV. At a local price of 12 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh), fueling an average EV costs about $3.43 for every hundred miles driven, while an ICEV at the current fleet average of 22 miles per gallon (mpg) costs $19.13 at today’s average local price of $4.21 a gallon. (10) Even a Prius ICEV at 56 mpg costs $7.52 for those same hundred miles, more than twice as much as an average EV. On top of that, EVs don’t need oil changes or much other regular maintenance.

With all these advantages, EVs are catching on quickly around the world. They exceeded 5 percent of U.S. auto sales in 2022 and are forecast to comprise from 30 percent to over 50 percent of U.S. sales by 2030. (11) Even this may be a conservative estimate. Since 2018, the Boston Consulting Group has more than doubled its EV sales projections for 2030 (12) and will certainly increase them again, given the IRA passed two months after their 2022 forecast. Meanwhile, a dozen automakers have announced that they plan to stop building ICEVs by as early as 2030. (13)

Charging Is a Major Issue

Still, obstacles remain for EV buyers even as prices keep dropping. EVs have to be charged. Unlike filling up an ICEV, which takes 10 minutes even if you have to wait in line, most EVs take six to eight hours to charge fully on Level 2 chargers, the fastest type you can install at home. And, even though ranges are increasing, most are still under 300 miles. Increasing numbers of EVs have DC fast charging capability (14), which can add over 100 miles in a half-hour stop, though commercial vendors typically charge two to five times as much per kWh as you would pay using a Level 2 charger at home. (15) This raises the cost of driving 100 miles to about $10.28, less than an average ICEV but more than the Prius. Most people rarely drive so far in a day that they need to recharge before the day is over, and, if you live in a house with a garage, you can plug in your car overnight. Or, if you park your car at work all day, installing some chargers there means your car will be fully charged when you are ready to leave. But, if EVs are to be practical for working-class families, we also need to ease the cost and convenience for apartment and condo dwellers, and those without garages. This is a problem we need to solve quickly in Whatcom County.

Carrots and Sticks

So, where are the carrots? How do we ensure that people wanting to switch to an EV have access to convenient, affordable charging? Home charging is the most convenient, and the IRA has made a good start by reinstating the tax credit for 30 percent of the cost of installing a home charger, up to $1,000 (which is way more than you need to spend for a serviceable charger). For those with a driveway but no garage, there are weatherproof chargers with locks to prevent power theft and discourage vandalism. (16) To cut the cost to first-time buyers even more, could car dealers eager to increase their EV sales buy chargers in bulk and bundle them at cost to EV purchasers?

There are also sticks. Increasing numbers of jurisdictions have passed building code amendments requiring charger-ready electrical circuitry in all new construction. Codes can require all new multifamily housing, such as rental apartments and condominiums, to have EV-ready wiring (where chargers can be installed) in all off-street parking designated for tenants or condo owners, and can require businesses to do the same in employee parking. International building codes updated in 2021 now incorporate these requirements, and they will be submitted to the Whatcom County Council for approval before July of this year, when the state has mandated that they be adopted. King County has gone a step further and will soon require new apartment buildings to install actual chargers, not just EV-ready wiring, in 10 percent of their parking spaces. (17)

It may be unreasonable to require owners of existing housing or businesses to install chargers or rewire their buildings for future installation, but it is very reasonable to offer incentives to do so. The IRA also offers tax credits up to $100,000 for businesses that install multiple chargers. (18) It makes sense for the hospitality business — hotels, motels, and private rentals, such as Airbnbs — to install chargers, as visitors may have driven all day to reach their destination and will need to recharge when they get there. If the hotel has chargers, guests can recharge while they sleep. Especially with IRA incentives, installing chargers can be a smart business expense, a valuable perk to offer to their guests.

The state of Washington has also authorized grants to local governments, tribes, and utilities to “deploy charging stations in rural areas, office buildings, multiunit dwellings, ports, schools and school districts, and state and local government offices.” (19) All of these public and private entities in Whatcom County can thus take advantage of both federal and state funding to build out our charging infrastructure.

Problems in Practice

However sensible and straightforward (and even funded!) this all seems, actually doing it presents some serious challenges. The first is the sheer quantity of charging infrastructure we will need. At present, only about 1.4 percent of Whatcom County’s vehicles are EVs, but electrification may raise that to 40 percent by 2035. Home and workplace equipment can and should provide most of the charging capacity. Currently, 63 percent of Whatcom homes are owner-occupied. At two vehicles per home, if 40 percent of cars are EVs, around 37,000 homes will need a charger. (20) Before long, just about every home that can install a charger will have one: they will be as ubiquitous as refrigerators or washing machines. And, at $500 for a Level 2 charger, (21) that will be a minor expense compared to buying a car anyway.

So, that’s great if you own your garage, but what about the 37 percent of Whatcom County residents who rent their homes or apartments, or the several thousand homes in older Bellingham neighborhoods that lack garages or even driveways? Car ownership is only modestly less common among renters. Ninety-two percent of those who commute do so by car. Less than 11 percent carpool. So, if 40 percent of them own EVs by 2035, another 23,000 cars will need regular charging. If that occurs about every three days, then 8,000 more chargers will need to be installed in apartment and workplace garages and parking lots. Revised building codes will assure that new homes and businesses will provide access to chargers, but retrofitting existing apartments and businesses will depend heavily on federal or state incentives in the form of tax credits or rebates.

This still doesn’t cover everyone. For whatever reason — living in an old building not retrofitted for EV charging, a power outage the night you were planning to charge, underestimating the miles you might drive in a day, or just driving by to somewhere else — there will be a need for public charging stations. The City of Bellingham anticipates that it will need about 4,000 public chargers in addition to those in homes and workplaces. We estimate that the rest of the county will require another 4,500 or so, for a total of 8,500 in the county.

This brings up the second big challenge for EVs — equity. Residents with home chargers can pay Puget Sound Energy’s (PSE’s) current rate of 12 cents per kWh, but Bellingham will charge 25 cents at the 47 public stations it’s currently building (22), while EvGO, Electrify America and other commercial vendors charge anywhere from 25 to 61 cents per kWh. (23) Over an average EV’s life span, even the lowest commercial rate would require spending about $13,000 dollars more than charging at home. So, those unable to install a home charger — mainly lower-income people — will end up paying more to drive than the more affluent. If such inequities are not reduced or eliminated by some sort of governmental or market incentives, many who wish to join the fight against climate change will not only find themselves excluded, but the transition to renewable energy will also remain incomplete, such that climate change will continue, albeit at a slower pace.

Convenience and safety also present obstacles to regular public charging. How tenable and safe is it to leave your car charging, often for hours, blocks away from work and home? If it takes four to five hours on a Level 2 charger, and you can’t charge at a convenient time of day, DC fast charging seems like the only solution for a fully electric EV. If that is unavailable, plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) with much smaller batteries may be the only practical interim solution. (24)

There are also larger-scale issues. If 40 percent of our total fleet are EVs by 2035, PSE will need to add about 250 gigawatt hours, or about 10 percent, to our electrical supply, just for EVs. (25) Thereafter, if EVs increase to nearly 100 percent, that will add another 12 to 15 percent to demands on the grid. This provides yet another reason to charge at home rather than work, because home charging occurs mostly at night when power demands are at their lowest.

Emissions Reduction

As we add all this electricity, we must bear in mind that the main purpose of electrification is to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions and thereby mitigate climate change. According to the Washington state Commerce Department, PSE, which supplies almost all residential and commercial electricity in the county outside of Blaine, generates about 58 percent of its electricity from natural gas and coal, and almost all of the rest from hydroelectric and wind. Because EVs are much more energy efficient than ICEVs, even an EV using PSE’s electricity reduces greenhouse gas emissions. An average ICEV will emit 4.4 metric tons of greenhouse gases in a year. An average EV on PSE’s current mix will still emit about 1.4 tons. But, if PSE becomes fully green, one EV’s emissions would fall to about a tenth of a ton, eliminating 98 percent of vehicle emissions, or 350,000 tons of greenhouse gas per year. So, just switching to EVs will cut our non-refinery emissions by a fifth, a huge help to our local climate mitigation efforts.

There Are Risks

All of these technical fixes are feasible if we have the will and the funding, much of which is already available. But there are also more general challenges. The biggest among these is planning. The future beyond the next few years is not precisely predictable. We don’t even know how many EVs Whatcom County may really have by 2035, which is only 12 years away. Sales have outstripped predictions for the last few years, but this trend may not continue. Supply chains for critical materials may present bottlenecks for EV battery production, or resolve as quickly as they develop. For example, a combination of newly discovered deposits and battery designs that use less cobalt has turned a widely lamented bottleneck in 2022 to a surplus in early 2023. (26) If our charging infrastructure is built too slowly, long waits at charging stations may replay the gas lines of the 1973 oil crisis.

At the same time, other factors caution against a crash program to build fast chargers everywhere, such as President Biden has touted in some recent speeches. Battery materials may still be in short supply. Mining companies may not see these minerals as worth the investment. There are severe ethical questions, including environmental degradation from mining battery materials. Indigenous and local populations in many countries are concerned that indiscriminate mining in the service of mitigating climate change may be almost as destructive to their lands and livelihoods as the oil and gas fields and the coal and uranium mines that fueled our previous growth in energy. (27)

There are also other risks in going too fast. Improvements in vehicle technology may reduce the time needed for Level 2 charging. Cars will certainly develop more range, even with today’s lithium-ion batteries; many higher-priced EVs now have ranges over 300 miles, and a few really pricey models can go 400 miles or more on a charge. New technologies such as solid-state batteries may eventually store much more energy for the same weight, giving vehicles more range or less weight, thus reducing charging time for the same distance. This may in turn reduce the need for public chargers. For now, such technologies are still a few years in the future. (28) But, if we build our charger infrastructure too quickly, particularly DC fast chargers, we risk leaving white elephants at every rest stop and many parking lots.

Plan Wisely

We are still very early in our transition to an electrified transportation system. New technologies are promised, then fizzle; others may bloom with unanticipated speed. Growth models are only as good as the data fed into them, and the farther out we try to project, the less accurate our projections may be. So, the challenge is to pay close attention to developments in both the technology and the economy, and adjust our planning and our investments accordingly. Yet, it is almost certain that two decades from now, most of us will be driving EVs. The road ahead may have twists and turns, but with wise planning and EVs of the future, our transportation system will get there.

The authors would like to thank Phil Thompson, Ellyn Murphy, and Sally Hewitt for help at all stages of writing this article.

Endnotes

1. United States Environmental Protection Administration, “Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” Updated 5 August 2022. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions

2. United States Environmental Protection Administration, “Fast Facts on Transportation Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” 14 July 2022. https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/fast-facts-transportation-greenhouse-gas-emissions

3. Ian Tiseo, “Greenhouse gas emissions from on-road vehicles in the United States in 2020, by type,” Statista, 6 February 2023.

4. Whatcom County Climate Action Plan, 2012, page 20.

5. Point2, “Whatcom County Demographics,” https://www.point2homes.com/US/Neighborhood/WA/Whatcom-County-Demographics.html

6. Wikipedia, “Tesla Model 3.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tesla_Model_3

7. Find My Electric, “Electric Car Prices: Average Electric Car Cost in 2023” https://www.findmyelectric.com/blog/electric-car-prices/; “2023 Cars.com Affordability Report: Best Value New Cars.” https://www.cars.com/articles/2023-cars-com-affordability-report-best-value-cars-461158/

8. Recurrent, “Used Electric Car Prices & Market Report—Q1 2023” https://www.recurrentauto.com/research/used-electric-vehicle-buying-report

9. The Car Connection, “Electric pickup trucks: A complete guide,” https://www.thecarconnection.com/news/1130049_where-are-the-affordable-electric-pickup-trucks

10. https://gasprices.aaa.com/?state=WA

11. Evadoption, “EV Sales Forecasts” https://evadoption.com/ev-sales/ev-sales-forecasts/

12. Liz Najman, “EV Adoption: Trends & Statistics in the U.S. Recurrent, 22 November 2022. https://www.recurrentauto.com/research/ev-adoption-us

13. Aaron Spray, “These 8 Car Companies Are No Longer Investing In ICE Cars (Plus 1 Stubborn Company That Is).” Hotcars, 14 July 2021. https://www.hotcars.com/car-companies-no-longer-investing-in-ice/#stellantis-chrysler-fiat-peugeot-citroen

14. Warnings that DC fast charging dangerously depletes battery capacity appear from recent research to be overstated; frequent DC fast charging degrades batteries a little faster than constantly using Level 2 chargers. See among others Ioanna Lykiardopoulou, “Is fast charging bad for your EV battery?”, TNW 9 August 2021. https://thenextweb.com/news/is-fast-charging-bad-ev-battery-degradation

15. Gabe Shenhar and Alex Knizek, “Can Electric Vehicle Owners Rely on DC Fast Charging?” CR Reports, 7 November 2022. https://www.consumerreports.org/cars/hybrids-evs/can-electric-vehicle-owners-rely-on-dc-fast-charging-a7004735945/

16. https://www.amazon.com/Outdoor-Charger-Station/s?k=Outdoor+Charger+Station

17. King County, “Council approves requirement for electric vehicle charging in new development,” 13 July 2021. https://kingcounty.gov/council/mainnews/2021/July/7-13-electric-vehicle-charging.aspx

18. Kelley R. Taylor, “The Federal EV Charger Tax Credit is Back.” Kiplinger, 2 February 2023.https://www.kiplinger.com/taxes/605201/federal-tax-credit-for-electric-vehicle-chargers

19. U.S. Department of Energy, Alternative Fuels Data Center, “Electricity Laws and Incentives in Washington.” https://afdc.energy.gov/fuels/laws/ELEC?state=WA

20. For the rare household that needs to charge two vehicles at once, there are dual-port chargers on the market. See Mike Belcher, “Dual EV chargers,” EV Adept, 15 February 2023 https://evadept.com/best-dual-ev-charger-for-two-cars/

21. See Manta, “EV Charging Installation Costs in Bellingham, WA, 2023.” https://www.manta.com/cost-ev-charging-installation-bellingham-wa

22. Erik Wilkinson, “Electric vehicle owners in Bellingham will now have to pay to charge,” King5 News, 29 December 2022. https://www.king5.com/article/tech/science/environment/electric-vehicle-owners-bellingham-pay-to-charge/281-18e40176-7aed-4a3c-a255-ea459a140da9

23. Electrify America, “Pricing and Plans for EV Charging,” https://www.electrifyamerica.com/pricing/; EVGo, “EVGo fast charging pricing,” https://www.evgo.com/pricing/

24. Dan Mihalescu, “2023 Mazda MX-30 PHEV Brings Back Rotary Engine As Range Extender, Inside EVs,” 13 January 2023. https://insideevs.com/news/630894/2023-mazda-mx-30-phev-brings-back-rotary-engine-as-range-extender/

25. Find Energy, “Whatcom County, Washington, Electricity Rates and Statistics.” https://findenergy.com/wa/whatcom-county-electricity/

26. “Cobalt, a crucial battery material, is suddenly superabundant.” The Economist, 16 February 2023. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/02/16/cobalt-a-crucial-battery-material-is-suddenly-superabundant

27. Nicholas Wallace and Austin Irwin, “Longest Range Electric Cars, Ranked.” Car and Driver 7 June 2022 https://www.caranddriver.com/shopping-advice/g32634624/ev-longest-driving-range/

28. Oraan Marc, “Where Are Those Solid State Battery EVs? How Long Do We Have to Wait for Them and Why?” Autoevolution, 15 January 2023. https://www.autoevolution.com/news/where-are-the-solid-state-battery-evs-how-long-do-we-have-to-wait-for-them-and-why-208128.html

_____________________

Stevan Harrell is a retired professor from UW Seattle School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. He and his wife Barbara live in Bellingham and drive an EV. He is a member of the Whatcom County Climate Impacts Advisory Committee.

Ray Kamada, former director of the Environmental Physics Group at the Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, is also a member of the Whatcom County Climate Impact Advisory Committee.