by Luisa Loi

Editor’s Note: This is an update to the Climate Action Fund article printed in the July edition of Whatcom Watch. It reflects action taken by Bellingham’s mayor the day after the paper went to press.

Bellingham Mayor Seth Fleetwood announced a June 21 “strategic pause” on the proposed Climate Action Fund (CAF), a tax originally considered as a potential measure to include in the November 2022 ballot.

The decision was made in light of concerns about timing, lack of details in the draft proposal, and potential conflict with four other ballot measures, according to a press release from the City of Bellingham.

The draft proposal for the CAF, presented to the council on June 6, indicated a property tax levy as the best way to create the fund. The levy would have raised $6 million a year — with an annual 1 percent increase for 10 years — to support the Climate Action Protection Plan’s initiatives to address community and municipal carbon emissions.

The competing levy proposals would fund the Emergency Medical Services (EMS), childcare support, a new jail project in Whatcom County, improvements to school buildings and new construction projects.

Due to insufficient state and federal funds, many initiatives are underfunded or not funded at all. In the press release, Fleetwood announced he is proposing more funding for climate action programs in the 2023-24 budget that would address emissions from municipal operations. The budget proposal, which will be developed this summer and presented in October, will also include details about the creation of the Office of Climate Action to manage investments. According to Communications Director Janice Keller, the mayor intends to form the office by the end of the year.

Fleetwood said that, by gaining more support from the community, the current draft proposal will serve as the base to organize the next steps.

“The time we have invested in shaping and vetting this proposal has been invaluable in furthering a deeper understanding of the challenges of the work ahead of us,” he said.

Keller said they don’t know when the fund will be re-proposed yet.

Now What?

In 2020, the council amended the 2018 Climate Action Plan by adding 10 more measures, including the creation of the Climate Action Fund — now on hold.

Without the CAF, providing additional funds from the 2023-24 budget — which Fleetwood announced he would request — could support the Climate Action Plan in achieving 85 percent reduction of municipal greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and 100 percent by 2050 below 2000 levels.

With the levy, the fund would have also helped achieve a 40 percent reduction of community greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and an 85 percent reduction by 2050 below 2000 levels. These are more goals set by the latest Climate Action Plan.

It’s still unclear if these objectives are possible without the tax levy revenue, but Fleetwood remains hopeful.

“With additional resources, we will be able to accelerate achieving our climate goals,” Fleetwood said. “In addition, a sustainable, dedicated Climate Action Fund would increase the likelihood of leveraging private, state and federal funds, further accelerating our climate ambitions by multiplying the investments.”

In the meantime, as Climate and Energy Manager Seth Vidaña announced during a City Council meeting in March, the city is working on a variety of projects, including:

• Installing 90 electric vehicle charging stations with a $1.5 million grant from the Department of Commerce and $500,000 from the Transportation Fund.

• Developing programs to electrify new buildings, and help 10,000 houses built before 1990 reduce their emissions by providing incentives and requirements.

• Installing a solar plant in Whatcom Falls Park, which will serve 50 average homes with focus on low-income resident.

The Levy: Original Expectations

Deputy Finance Director Forrest Longman explained the math behind the proposed property tax levy, which would have collected $6 million in its first year and added to other property tax revenue (about $29.3 million next year), totaling an estimate of $35.3 million.

To collect the necessary revenue, the levy would have increased from the current $1.57 to $1.97 (bumped from $1.94 to account for potential refunds, he said). The first year’s $0.37 levy rate limit derives from the city’s overall assessed valuation (or the total value of all property in town, which amounted to $16 billion in 2022) divided by 1,000, and then from dividing the revenue target (which starts at $6 million) by that amount.

This means that, during the first year of the levy, for every $1,000 of assessed valuation on a house, the owner could have been charged up to $0.37. Data presented to the council on March 28 suggested that, in Bellingham, the average assessed value home (about $500,000) would pay around $186, or $15.50 a month. The following year, with an increase of the property value, the new revenue target would have risen by 1 percent. In this case, the new goal would have been to collect $6,060,000 (60,000 is 1 percent of 6 million, the original revenue target for the CAF).

Because of the formula used to calculate levy rates, larger revenue targets and property values would have meant smaller levy rates. However, a reduced rate doesn’t necessarily equal lower taxes for everyone.

State limit for property tax is $3.60 for every $1,000 assessed property value, but Longman said the city wouldn’t have been at risk of hitting that rate.

What the Science Tells Us

The University of Washington’s Climate Impacts Group has found that greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere have never been this high for at least 800,000 years. Human activities have been so intense they caused global temperatures to rise by one degree Celsius over pre-industrial levels.

According to the Impacts Group, if global temperatures increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius, by 2050 Washington could experience dramatic changes that would put at great risk the environment, people’s health, and the economy. In 2020, the legislature stated that avoiding a global catastrophe is only possible by drastically and immediately reducing global greenhouse gas emissions.

Projections indicate a 67 percent increase in the number of days above 90 degrees Fahrenheit, smaller water storages due to reduced snowpack, increased risk of flooding in winter, drier and warmer streams (which would affect the already vulnerable salmon and cause conflicts over water resources), and coastal flooding caused by the sea level rising up to 1.4 feet.

Some changes are already happening. In summer 2021, Washington experienced the infamous Pacific Northwest Heat Dome which, according to the Department of Health, killed 100 people in the state between June 26 and July 2, and hit all-time record temperatures in Bellingham.

Making an Impact

“Our City is doing the work that every community in the world should be doing, taking action to meet our climate goals and continuing the important work of building a sustainable, equitable and thriving City,” Fleetwood said in the press release, a belief he and Vidaña have expressed in previous council meetings.

In February 2022, the council passed an ordinance that mandates commercial and large multifamily buildings to be built all electric. Bellingham is the third city in the state to do so, Vidaña said, following Seattle and Shoreline.

“After that ordinance was passed, we began fielding questions from people all across the region who wanted to see their city pass similar legislation,” Vidaña said.

As more cities adopted similar ordinances, Washington followed: on Earth Day 2022: the state adopted an energy code restricting natural gas use for heating and requiring the use of electric heat pumps instead, which, according to the Washington State Building Code Council, will go into effect next year.

The beginnings of the city’s climate leadership date to 2005 with the Cities for Climate Protection Campaign, a network of 546 cities across the globe committing to reverse climate change.

This commitment led to the city’s first Climate Protection Action Plan in 2007. This first version of the plan aimed to reduce the community’s greenhouse gas emissions by 7 percent and 28 percent below 2000 levels by, respectively, 2012 and 2020. At the same time, it committed to reducing city government emissions by 64 percent and 70 percent for those same years, below 2000 levels.

It also led the way for the Greenhouse Gas Inventory — an estimate of the amount of greenhouse gasses released in the city to track progress for future targets. The inventory tracks two measures: greenhouse gasses released by city-controlled activities and those released by the community at large.

Between 2000 and 2012, municipal emissions decreased by 69.5 percent thanks to 23 emission reduction measures, exceeding the 64 percent target set in 2007 for this category. At the same time, 48 emissions reduction measures made community emissions drop by 7 percent, according to the plan’s webpage.

In 2015, an increase in emissions delayed progress towards future targets, a shortfall that the current 2018 Climate Action Plan is trying to make up. In September 2021, Fleetwood joined the Race to Zero campaign and established that the 2023 Climate Action Plan’s targets would be reducing carbon pollution by 59 percent by 2030 and 100 percent by 2050. It’s unclear how the pause on the Climate Action Fund will delay this effort.

Areas of Investment?

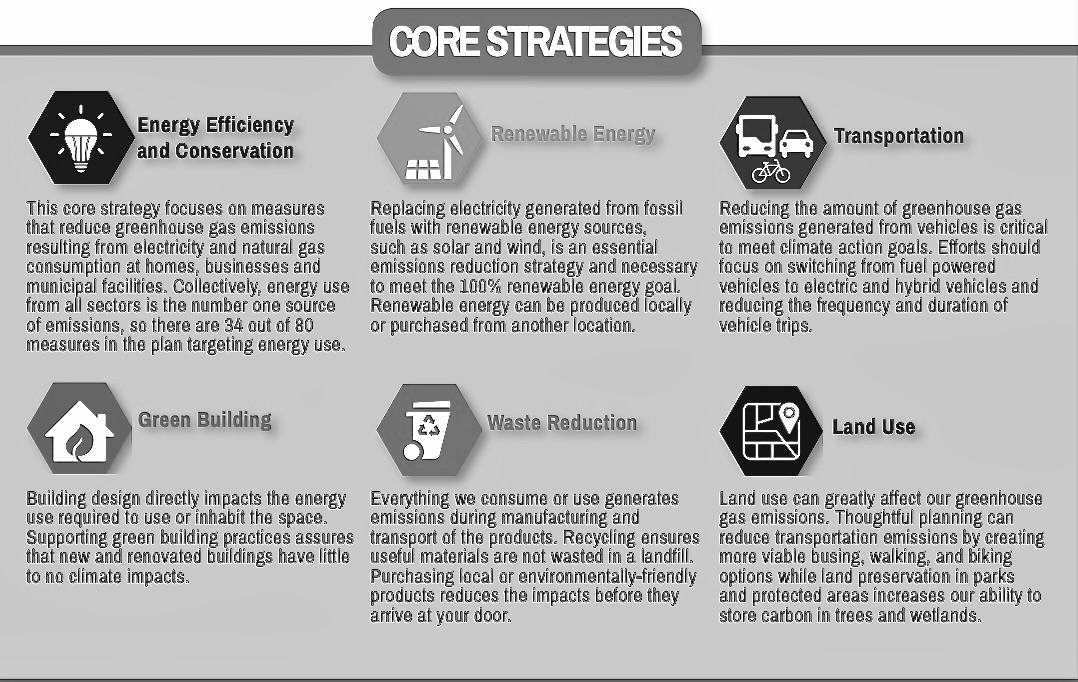

On April 11, Vidaña presented to the Bellingham City Council what would have been the fund’s areas of investment:

• Generating or buying renewable energy. Investments in this area were estimated to cost $4.5 million in its first year to buy electricity, and were expected to decrease with more locally generated energy.

• Supporting low carbon transportation programs and infrastructure. Through 2030, this area could have either required $60 million just to buy electric vehicle chargers, or $15 million if the city incentivized their purchase.

• Electrifying buildings and making them energy efficient, and developing a green workforce. Vidaña gave a cost estimate of $900 million (or $300 million if the city adopted local incentives) through 2050.

• Adapting to the impacts of climate change, like providing air conditioning and air filtration equipment, or creating tree planting programs. Their cost estimate is unknown.

According to Vidaña, at least 50 percent of Climate Action Funds would have been dedicated to directly supporting the community, with a focus on equity, workforce development, social justice and vulnerable people.

He said vulnerable groups include children, elders, people of color, indigenous people, low-income residents, immigrants with limited English proficiency, disabled people, individuals with preexisting medical conditions and vulnerable occupational groups.

In Washington, according to the state Legislature, those most affected by the health and economic impacts caused by climate change are within these communities.

Support for vulnerable communities could have looked like: subsidizing additional costs for renewable energy, investing in community solar options that offer financial benefits, helping residents find used electric vehicles and incentivizing charging stations, training and hiring from overburdened communities, creating public cooling stations and more, according to the draft resolution proposal.

Concerns About the Fund

Trevor Smith, political director of the Laborers’ Union Local 292, said that earlier this year the representatives of different labor unions in the state submitted a language proposal to the city. This language, meant to be implemented in the fund, would have specified how the carbon industry workforce would transition into clean energy jobs without losing benefits and workers.

“[Workers] want to transition for living wages, they want to do it for an apples-to-apples comparison to what they’re making now, with insurance for them, their families, and pensions,” he said. “It doesn’t help anybody if we do heat pumps, but then nobody can afford to live here.”

During a meeting with the Climate Action Committee, Fleetwood said there would be a session to discuss the proposal, but, four months later, Smith said he never heard back and many of his questions remained unanswered.

While acknowledging the fund’s benefits, the importance of acting now against climate change, and the challenges of designing an equitable tax system, Climate and Energy Policy Manager Simon Vickery from RE Sources said he would’ve spent more time brainstorming with stakeholders to develop better revenue solutions for climate action.

“If we just move fast, we could cause harm in the process,” Vickery said. “We could make life more difficult for vulnerable populations, and put some people out of a job.”

Tara Villalba, member of the Bellingham Tenants Union, believes a property tax levy is an unfair solution.

“Require greenhouse gas emitters to take responsibility for the emissions that they make rather than making the poorest people in a city bear the burden of the emissions that industry is causing,” she said.

Because tenants are most vulnerable to climate change, they tend to support environmental initiatives, Villalba said. Renters can’t install air conditioning systems, nor can they change the heating efficiency of their apartments, or make other necessary modifications to adjust to the weather. Those decisions are for landowners to make.

Although renters may feel strongly about climate change, Villalba said many of them can’t afford to pay more to support green initiatives.

“My own landlord says my rent goes up because his property taxes go up,” she said.

The Climate Action Fund’s draft resolution acknowledged community concerns about property taxes and rising housing costs, but the levy’s math suggests that rent costs depend mostly on the value of the property — which is affected by market demand and availability — rather than on property taxes.

“According to the Washington Center for Real Estate Research, from fall of 2019 to fall of 2021, rents in Whatcom County increased by 25 percent,” the draft resolution says. “During that same period, the average sale price of a single-family home increased 30 percent and property taxes increased 5 percent.”

“Our vacancy rate is incredibly low in Whatcom County,” said Deputy Finance Director Forrest Longman, explaining how, when they see high demand, landlords may justify raising the rent.

State law forbids municipalities from imposing rent controls; however, city administrations can enter into agreements with private entities that decide how much they charge tenants.

“Two years into a pandemic, the fact that rent raises are going up, and every effort there is to introduce some sort of rent control is completely defeated, is a problem,” Villalba said.

When presenting the fund, Vidaña said a property tax levy is the most reliable revenue source to fund a long-term project, as it is more consistent and predictable than taxing natural gas use or the utility companies. The cost of gas changes frequently, and people consume less during warmer seasons, significantly affecting revenues.

Those who live in older and less expensive homes might not be able to reduce their natural gas use because of poor insulation. According to the draft resolution, the property tax would have imposed the least burden on low-income people compared to other options.

Councilmembers’ Opinions

During the June 6 meeting, some City Council members expressed their own reservations about the funding proposal.

Councilmember Lisa Anderson said the community wanted to know whether these initiatives to address global issues would benefit them and be worth the extra costs. She said she spoke with college students, people with fixed incomes, low-income people and senior citizens on social security.

“They see it as whatever we do, it won’t even be a drop in a cup,” she said.

“People are tax fatigued,” Anderson said. “[Homeowners] want to know if they’re gonna get low-interest or no-interest loans, so they don’t have to refinance that house to put those heat pumps in or the solar power.”

Anderson said she would have liked to see the fund being spent on the community as much as possible by supporting local energy generation (a stance shared with Councilmember Hannah Stone). She found that $6 million “spreads thin rather quickly,” and felt uncomfortable at the idea of giving taxpayer money to a for-profit company like Puget Sound Energy to buy electricity. She suggested purchasing the energy from local nonprofits instead.

Vidaña said that, although working with local businesses was the priority, there was a possibility the city wouldn’t be able to find timely local options at a reasonable cost. If so, working with businesses outside the community may be the best option.

He used the plans to install 9,700 electric vehicle charging stations and provide 16,000 homes with heat pumps as two examples.

“Bellingham does not have a current manufacturer of EV charging equipment, nor do we have a manufacturer of heat pumps,” he said. “A short way of saying this is that we have a lot of work, not much time to do it, and limited paths forward.”

Councilmember Daniel Hammill said he was concerned about competition with other ballot initiatives, and that the issue needed to be addressed by a statewide effort.

“It’s a gamble that other cities will look to us with our leadership and say ‘Let’s do it,’” he said. Inspiring other municipalities with the Bellingham Home Fund, for example, was disappointing, he said. “What if it happens in five years or 10 years, or doesn’t happen?”

He said the climate fund was at risk of failing because it lacked a campaign to inform and encourage voters (which was also brought up by Councilmember Edwin H. Williams). Fleetwood acknowledged the tight timing, but said at the time he believed the city had enough time to spread the word effectively.

Anderson and Martens also expressed concern for the timing and the lack of detail in the resolution.

“I would like to be able to tell people specifics on how some of this funding would be spent, and how some of the funding won’t be spent,” she said. “And it’s not here for me.”

Councilmember Michael Lilliquist agreed with Anderson on the need to prioritize the local community, but said the fund should have been approved. “The cost of cooling our homes and preventing people from suffering from … health problems is also caused by climate change.”

Before his decision to put the fund on hold, Fleetwood said there was no better time to act than now.

“I have this fear in the coming years that by some people’s estimation, the time is never going to be just right to do something like this,” he said. “I don’t know if there’s ever going to be a perfect time, especially given the reality that some people submit is the prospect of an impending recession.”

______________________

Luisa Loi is a student reporter based in Bellingham, with an interest in covering local environmental issues. You can learn more about Luisa through her LinkedIn (Luisa Loi), or by reaching out to luisaloi@live.com.