Time for Action

by Eric Hirst and Fred Likkel

Water is one of the most critical issues facing everyone in Whatcom County. We have a structure in place to manage our water resources, in the Watershed Management Board. But the process is failing with potentially serious consequences for our future.

Although we get plenty of rain and snow in the winter, summer is a different story. Streamflows drop dramatically, which increases stream temperatures and lowers dissolved oxygen levels, all of which are bad for salmon and other fish. At the same time, the hot, dry weather increases the need for water for homes, businesses, industry and, especially, agricultural irrigation.

Because of climate change, these forces are on a collision course. Here are a few relevant facts:

- The average Nooksack River flow in August is only 31 percent of the flow in January. For Fishtrap Creek, the comparison is even starker: August flows are only 5 percent of January flows. (1)

- Higher temperatures are leading to lower snowpack and shrinking glaciers; Mt. Baker glaciers have shrunk 40 percent over the past four decades. (2) These glaciers are a significant source of summer flows throughout the watershed.

- Impervious surfaces (buildings and pavement) in many areas of the lower mainstem of the Nooksack River have climbed dramatically. This results in increased winter runoff, and decreased groundwater storage that could boost summertime flow.

- Water use, for all sectors of society, in August is 5.5 times (550 percent) as great as in January. (3)

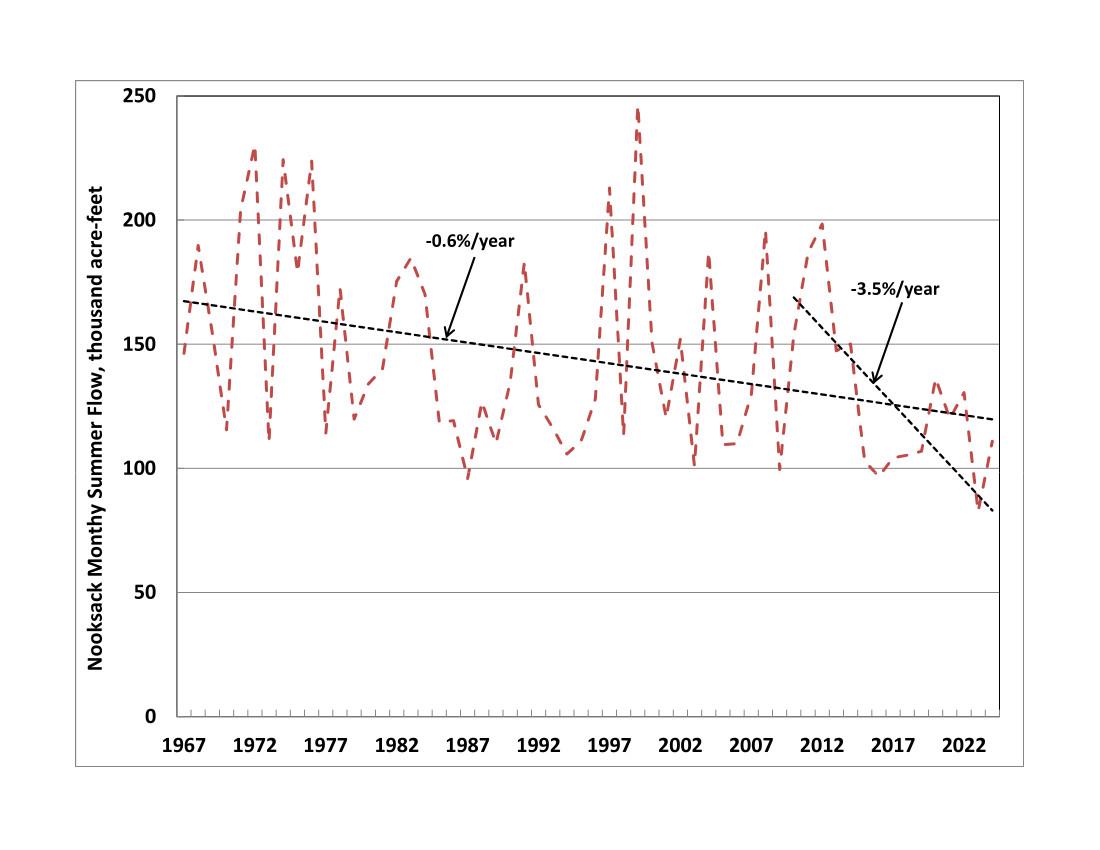

- Summer flows throughout the Nooksack River watershed have been declining at about 2 to 4 percent per year (Fig. 1). (4)

- Summer flows will almost surely continue to decline over the next few decades. (5)

Summer stream temperatures have been increasing at about 0.1 to 0.2oC per year. (6) This has led to multiple incidents of salmon dying before they reach their spawning grounds in the South Fork of the Nooksack River.

These many factors, adversely affecting both water supply and demand, argue for prompt action to develop new supplies, store winter water for summer use, and improve water-use efficiency.

Watershed Management Board

To deal with these water supply-and-demand issues (and others related to habitat and water quality), we have a well-established organization, the Watershed Management Board (WMB). (7) The predecessors to this board were created about 25 years ago and today include representatives from major local and state governments. Members include Lummi Nation, Nooksack Indian Tribe, Whatcom County, City of Bellingham, Public Utility District #1 (PUD), the small cities, and the state Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The WMB meets roughly quarterly and is supported by a Watershed Management Team, which, in turn, is supported by a Watershed Staff Team. These teams consist of staff to the leaders who serve on the board. (8)

The predecessor to the board developed its initial plan in 2005, since followed by other plans. A new plan (2025 – 2030) was adopted in May 2025, more than a year behind schedule. (9)

A Difficult Task

No doubt, the water challenges we face in Whatcom County are substantial: balancing the sometimes-competing needs of an increasing population, restoring salmon populations, and maintaining a viable agriculture base when summer water supplies are shrinking.

Future Population Growth:

As part of its work on a new comprehensive plan, Whatcom County projects a 30 percent population growth over the next two decades, an increase of almost 70,000 more people. (10) A key question in the comprehensive plan is where these people will live and whether water will be available, both physically and legally, in those locations.

Adjudication:

The Nooksack adjudication, now underway, is likely to take decades before the Superior Court issues legal water rights for instream flows and out-of-stream water users. The adjudication will clarify who has the right to use water, in what amounts, where and when. After the adjudication, the Department of Ecology (Ecology) has the authority to curtail or limit water use by junior water right holders to ensure that senior water rights are satisfied.

Climate Change:

We know, based on historical data, that summer streamflows throughout the Nooksack watershed are declining by a few percent per year and stream temperatures are increasing. At the same time, irrigation needs may increase because of higher summer temperatures and less summer rainfall.

Fig. 1. Nooksack River summer streamflow at Ferndale.

Solutions

Although managing our water resources is difficult, the tools exist to provide solutions. Fortunately, our issues are not caused by a lack of water overall. After all, our total yearly precipitation is projected to stay the same, even with climate change, over the next several decades. It will just be distributed over the year in differing patterns. Water management is the heart of the struggles our county faces.

In principle, we can reduce the large and growing gap between declining summer streamflows and increasing water demand in three ways:

- Add new supply (essentially, move water from locations where supplies are abundant to areas where water is scarce);

- Store winter water for summer use (including better forestry practices); and

- Increase water-use efficiency.

The quarter-century history in Whatcom County is one of many studies of water supply and storage, but not a single one of efficiency. If one views solutions as a 3-legged stool, consider the instability of a 2-legged stool.

Past Studies

Various entities conducted many studies over the past two decades of different supply and storage options, none of which has been implemented. These include, as examples:

- In 2009, the PUD commissioned a study of the costs to provide water to either the City of Lynden or to the Bertrand Creek watershed for agriculture and streamflow augmentation. (11) The water would come from the Nooksack River, either the PUD’s plant near Ferndale or Lynden’s intake on the Nooksack River. The project assessed eight combinations of sources and delivery points. The fixed costs (not including variable costs) ranged from about $400 to almost $3,000/acre-foot.

- In 2015, the Birch Bay Water & Sewer District proposed to Ecology to drill and test deep wells. The purpose of this project was to determine whether reliable supplies of clean water could be obtained without impairing surface flows in western Whatcom County.(12) Even after several years of data collection and analysis, there exist no estimates of the costs and cost-effectiveness of delivering this deep-well water to different delivery points. And no entity has elected to build and pay for the infrastructure needed to deliver this water to, as examples, Lynden and Cherry Point.

- In 2020, the City of Lynden received a grant from Ecology to explore locations where winter water could be stored and released through groundwater flows several months later to “increase flow in the Nooksack River primarily in June through October for habitat enhancement, stream flow augmentation, and water right mitigation purposes.” (13) Lynden issued a progress report, which did not include any estimates of the costs to build a managed aquifer recharge project at the two sites under consideration on the Middle and South forks. (14) This latest report also offered no numbers on the potential downstream flow benefits of projects at either site and nothing on cost effectiveness.

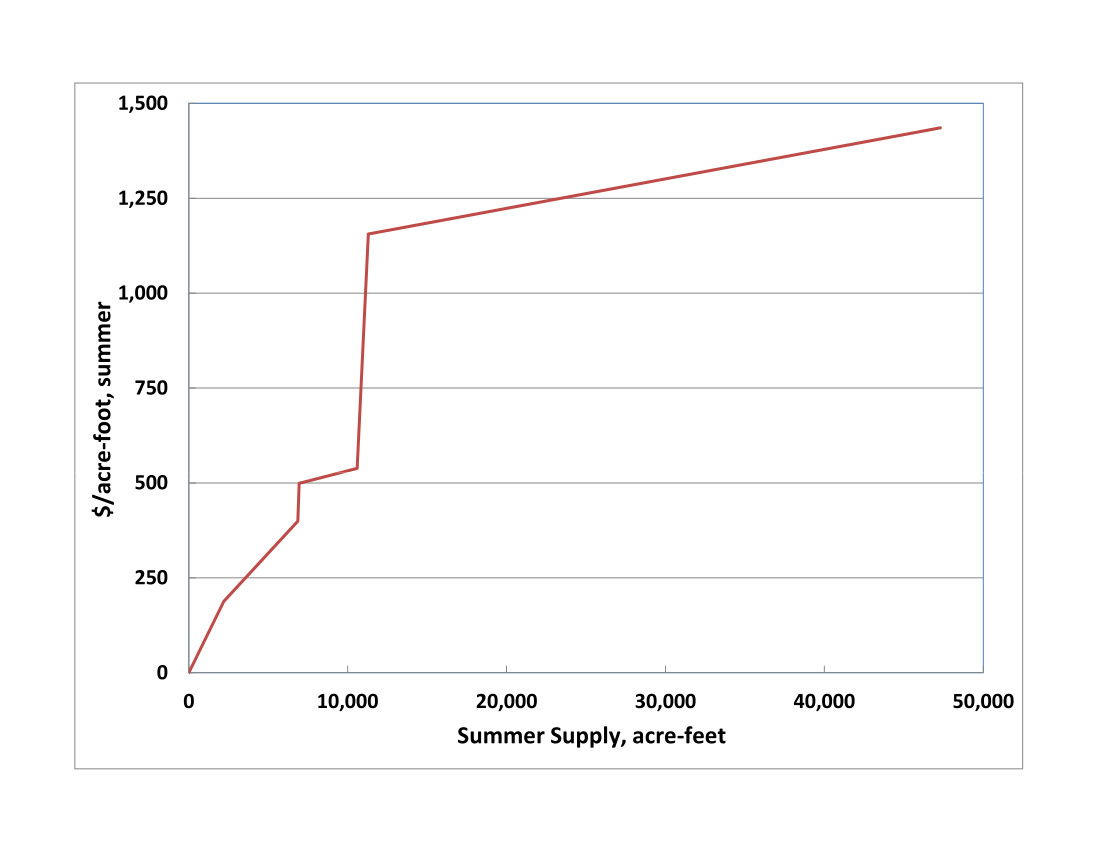

- More recently, eight storage options throughout the Nooksack watershed were assessed. (15) The report provides details on various benefits and costs for each project, including reduction in winter flooding and increased summer streamflow. The projects ranged from a very expensive North Fork Dam to modest natural storage projects (Fig. 2). Two projects in the South Fork watershed, Springsteen Lake Enlargement and Musto Marsh Storage Reservoir, are undergoing further investigation.

Farmers have proposed, and, in a few cases, demonstrated the streamflow benefits of shifting some water use from streams to groundwater and also from late-summer streamflow augmentation.

Fig. 2. Eight water-storage projects

that range in cost from less than $200/acre-foot to $1,400/acre-foot.

Leadership and WMB Plan

The WMB should provide leadership on water issues. Given the inherent diffi culties with reduced and changing natural water supplies along with existing and future demands, leadership should not just study options. Implementing projects is also vital. That takes decision-making and money and time. How has the WMB been performing?

The 5-year plan includes the word implement 25 times and the word implementation 65 times. Nevertheless, only one of the studies discussed in this article is even mentioned in the plan as a choice to implement. Instead, this plan proposes vague language and ignores crucial elements that need to be addressed for implementation to occur.

For example, two projects from a recent storage study, Musto Marsh and Springsteen Lake, are mentioned but with wording so vague that one has no idea what is to be done, when, and with what funding:

“… the strategy in initial development for the options in the alternative storage report that were identified by the WRIA 1 Management Team as priorities to pursue (i.e., natural storage, Musto Marsh, and Springsteen Lake).”

And, task 5 “Plan and Implement Water Management Solutions” says:

“… the WRIA 1 WMB will continue to identify, plan, and implement water solutions such as but not limited to water use efficiency, natural water storage, and other alternative storage options, coordinated through the WRIA 1 process.”

What does this vague, generalized language actually mean?

Haven’t we already “identified and planned” enough? Shouldn’t this plan include “shovel-ready” projects? We have studies that show what water storage can do. Studies and data show that converting agricultural irrigation from surface waters to groundwater wells would increase streamflows. Are there locations suitable for managed aquifer recharge projects (other than those currently investigated by Lynden) that should be explored? What can we learn about efficiency gains from experience in California and the Southwest, including U.S. Bureau of Reclamation projects throughout the Colorado River basin? Can we pursue funding for specific solutions?

Water-use efficiency has been neglected for the past two decades. And the 5-year plan continues that neglect. The plan, with no explanation, states that efficiency:

“… is not included as a standalone strategy and may be incorporated into local action plans (Strategy #6), planning and implementing water management solutions (Strategy #5) or other strategies as appropriate. It will also be considered during the annual adaptive management review of the work plan.”

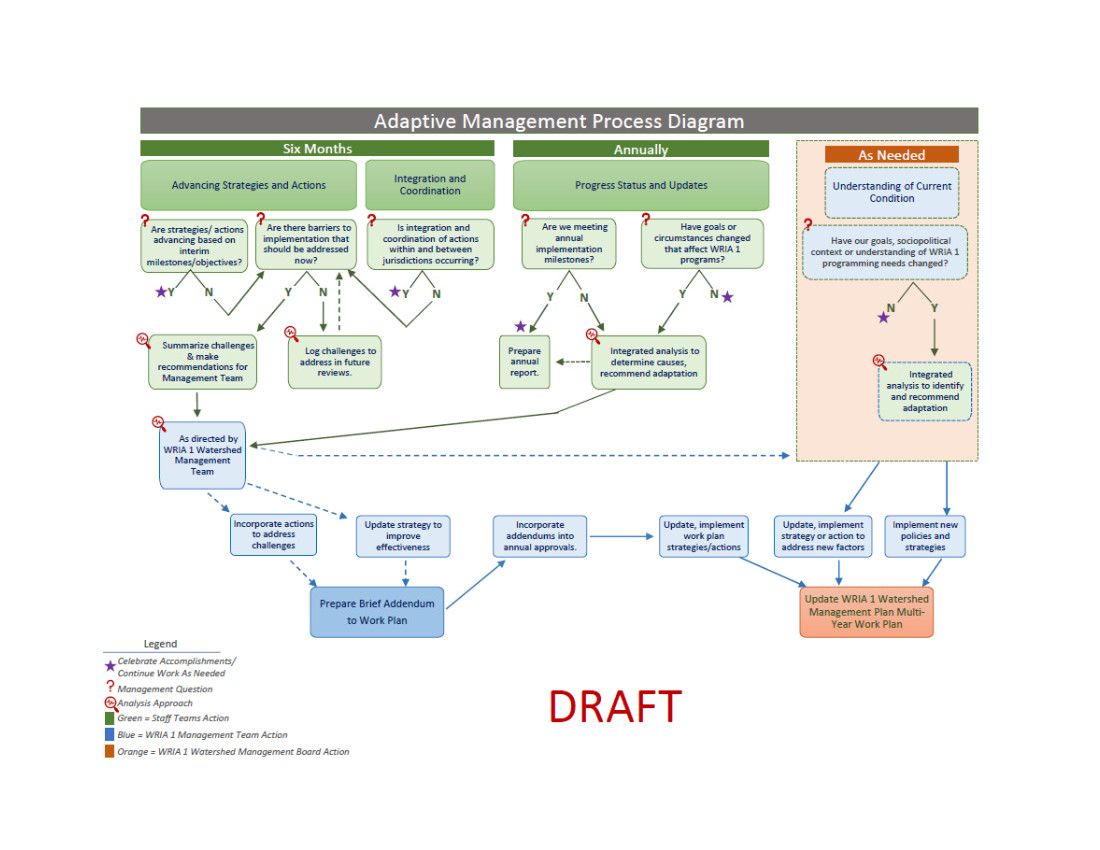

The plan is long on process and almost entirely devoid of action. For example, the plan includes an adaptive management plan (Fig.3). Adaptive management is a simple, useful strategy that essentially says “we’ll learn from our experience and use experience to help implement.”

Fig. 3. Proposed adaptive-management plan.

* See the pdf version of this plan at Hirst Likkel #3

Does this process really require ~20 boxes/steps to explain and implement?

In recent years, most of our leaders have agreed that finding solutions to these water issues is vital. Yet almost nothing of substance has happened. Other communities throughout the country with much greater issues regarding water supply, such as those in the Desert Southwest, and regionally the Yakima River watershed, have successfully begun working together and implementing solutions. What is keeping our leadership from doing the same things?

Barriers to Overcome

Future Population Growth:

Critical and sometimes difficult discussions are ongoing in Whatcom County about where to put all the people, and water needs to be a key part of that discussion. The 5-year plan is silent on this critical growth-management issue. It is also silent on the Coordinated Water System Plan, also under development by Whatcom County. (16)

More broadly, the plan presents no baseline on current out-of-stream (human) water use for homes, businesses, industry, and agriculture. And it offers no estimates (forecasts) of future human water use. How can we reduce the growing gap between declining supplies and increasing demand if we don’t even know today’s situation or what tomorrow might look like (and how climate change and population growth might affect future conditions)?

Adjudication:

Adjudication is a legal process that has the difficult task of sorting out 30,000 or more individual legal water rights. Nobody knows what the outcome of this process will be, but we need to recognize its existence and importance in projects that affect streamflows and human uses of water. The adjudication, by itself, will have no effect on actual streamflows and no effect on actual water uses.

The Whatcom adjudication is the largest basin-wide adjudication in state history. The Yakima Basin adjudication had only 8,000 users yet took 42 years to complete. Not a single basinwide adjudication in the United States has been solved without comprehensive settlement discussions. Yet, the WMB’s leadership, when facing its first major “we disagree” moment last year, decided “it would not be productive to engage in any further work related to positions in the WRIA 1 stream adjudication.” (17)

Climate Change:

Regardless of one’s opinion on the causes of climate change, the data are clear: our climate is changing and getting warmer every year. The University of Washington Climate Impacts Group concluded that, of all Puget Sound basins, the Nooksack River will have the greatest negative impacts. Although climate is mentioned five times in the plan, nowhere is there a discussion of how the effects of climate change will be incorporated into the board’s work over the next five years.

Conclusion

Leadership requires careful, yet definitive action. For over two decades, the WMB has conducted countless meetings among many groups, produced report after report, yet implemented few projects with virtually no improvement in our water supply-demand situation. True, water is a complicated and controversial subject, but where is the leadership toward solutions?

We have yet to adopt an action plan that includes specific projects to address these waterresource issues, including new supply, storage, and efficiency projects. Implementation would involve identification of specific problems in each basin (three forks, mainstem, and tributaries) and projects intended to resolve those problems. The plan would include budgets, funding sources, organizational responsibilities, monitoring, accountability, and milestones.

Indian water rights settlements often result in coordinated local parties and choices on solutions to implement. A settlement can bring an influx of federal, state and local funding for programs to improve fish flows, improve agricultural and municipal efficiencies, and create storage and other wet-water solutions.

We urge the Watershed Management Board to abandon its business-as-usual approach. Although adjudication is happening, it alone will not solve our water-resource issues. Recognizing this issue rather than ignoring it needs to be part of any plan. The only way we can move forward is to implement solutions that we agree on. The 2025 WMB plan gives little reason for hope. It should be revised to implement, and not just study critical water resource projects.

_______________________________

Eric Hirst has a Ph.D. in engineering from Stanford University, worked at Oak Ridge National Laboratory for 30 years as a policy analyst on energy efficiency and the structure of the electricity industry. He moved to Bellingham 22 years ago and remains active on local environmental issues.

Fred Likkel is the executive director of Whatcom Family Farmers, a nonprofit that represents the farming community through advocacy, outreach, and education. With over 30 years of experience in the local and state farming community, Fred believes strongly that protecting our farming community is a vital part of protecting our valued natural resources in Whatcom County.

Endnotes

- E. Hirst, Climate Change and the Nooksack Adjudication, April 2024.

- M. Pelto, personal communication, Nichols College, Sept. 15, 2023.

- E. Hirst, “How Water Use Affects Nooksack Streamflows,” Whatcom Watch, 34(3), March 2025.

- E. Hirst, “Nooksack Watershed Summer Water Temperature Trends,” Whatcom Watch, 33(12), Dec. 2024.

- R.D Murphy, Modeling the Effects of Forecasted Climate Change and Glacier Recession on Late Summer Streamflow in the Upper Nooksack River Basin, Western Washington University, Feb. 2016.

- See footnote 4.

- The WMB was created in response to the 1998 Washington State Watershed Management Act.

- In addition, the Planning Unit, individuals who represent agriculture, rural well owners, water districts, the environment, and others reports to Whatcom County.

- WRIA 1, Watershed Management Board 2025-2030 Work Plan, May 2025. WRIA 1 is Water Resource Inventory Area 1, roughly contiguous with Whatcom County, encompassing all of the Nooksack River and its tributaries.

- https://www.bellinghamherald.com/news/politics-government/article301565434.html R. Mittendorf, “Whatcom County bracing for 30% population growth over 20 years; here’s each city’s outlook,” April 4, 2025.

- Murray, Smith & Associates, Inc., Non-Potable Water Study for City of Lynden and Bertrand Watershed Improvement District, for Public Utility District No. 1 of Whatcom County, May 2009.

- D. Eisses and C. Lindsay, presentation on “Deep Aquifer Investigation Northwest Whatcom County,” Birch Bay Water & Sewer District, Feb. 2016.

- City of Lynden, “City of Lynden Nooksack River Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) Project,” Mar. 2020.

- City of Lynden, “City of Lynden Managed Aquifer Recharge Project Update,” letter to WRIA 1 Watershed Management Board, Nov. 29, 2023.

- Anchor QEA, Water Storage Alternatives Report, July 2024.

- Strategy 4 of the 5-year plan calls for integration with other local plans but is silent on how this integration is to occur and what projects this will encompass.

- The parties could not agree on how to interpret studies estimating the streamflows needed to maintain healthy salmon populations, probably the most important issue in both the adjudication and management of our water resources.