Preston L. Schiller

All in favor of sustainable transportation raise your right foot!

— David Brower (environmental wizard and hero)

Recent decades have seen a burgeoning interest in providing safe and sometimes pleasant ways for promoting walking and cycling. Yet, as Bellingham grows rapidly, sometimes by infill in appropriate areas and often by sprawling into low-density areas with low-density land-gobbling development without much urban infrastructure, it has become increasingly unpleasant or even dangerous to be a pedestrian in some areas of the city.

At the same time, the State of Washington, with the help of local District 42 Representative Joe Timmons and Senator Sharon Shewmake, has recently passed legislation, SB 5595, that could enable neighborhoods with streets without sidewalks to lower speed limits to better protect pedestrians and cyclists.

This article will discuss the city’s sidewalks and related policies and practices as well as ways of bringing greater encouragement of walking and cycling into existence. Suggestions will be offered about how SB 5595 could be enacted in several Bellingham neighborhoods.

photo by Preston L. Schiller

This sidewalk, an important walkway between the Fairhaven and Edgemoor neighborhoods and Fairhaven Middle School has been fenced and blocked for several months between Old Fairhaven Parkway and Cowgill Avenue, apparently to store a couple pieces of equipment that are not in use.

Bellingham Sidewalks

Downtown Bellingham and the commercial area of Fairhaven were largely developed in the latter part of the 19th century with ample provision of sidewalks, many of generous width. Building s abutted sidewalks, retail fronted the sidewalk, and entryways to offices and residences above were immediately accessible from the sidewalk. Sidewalks began to become more scarce, sometimes only abutting one side of a roadway, or disappearing altogether as one moved away from these centers.

Bellingham is not alone in this; over 28 percent of Seattle’s streets, mostly annexed after WWII, lack sidewalks. According to the City of Bellingham’s Public Works (PW) Department, there are approximately 315 linear miles of streets, 676 lane miles of streets (account for multi-lane streets), and 325 miles of sidewalk in Bellingham. While PW does not have a figure for streets without sidewalks, it is probably safe to assume that the percentage of Bellingham streets without sidewalks is higher, perhaps considerably higher, than the 28 percent figure for Seattle.

While many Washington municipalities make abutting property owners responsible for sidewalk maintenance, responsibility for sidewalks appears to be mostly assumed by the City of Bellingham. Abutting property owners are responsible for keeping sidewalks obstruction-free, including keeping shrubs and tree branches from interfering with walking. Parallel to this is the expectation that properties adjacent to the public right-of-way (ROW) on streets without sidewalks will maintain vegetation from encroaching on the roadway.

photo: Preston L. Schiller

Sidewalk at the intersection of State Street and Easton Avenue, close to Boulevard Park’s entrance, has been fenced and blocked for about a block in each direction for several months.

Missing Sidewalks, Sidewalks “Missing Teeth”

Traversing the city by any mode will remind one about how extensive the phenomenon of streets lacking sidewalks is. In some areas, sidewalks were provided for several blocks and then disappeared. The person on foot is fortunate if there is at least a shoulder on either side of the street for refuge from traffic.

Even where there is some degree of sidewalk provision, there are often gaps between developed and undeveloped properties, creating a “missing teeth” appearance along some streets that prevents a more complete network. This could be due to the city’s practice of waiting until a property without a sidewalk is developed in order to require that a sidewalk be provided, rather than having a citywide sidewalk fund that would distribute sidewalk funding to avoid the “missing teeth” orphaned among finished sidewalks. SB 5595, discussed on next page, presents ways that streets without sidewalks can still be made into relatively safe and pleasant places for walking, cycling, and socializing.

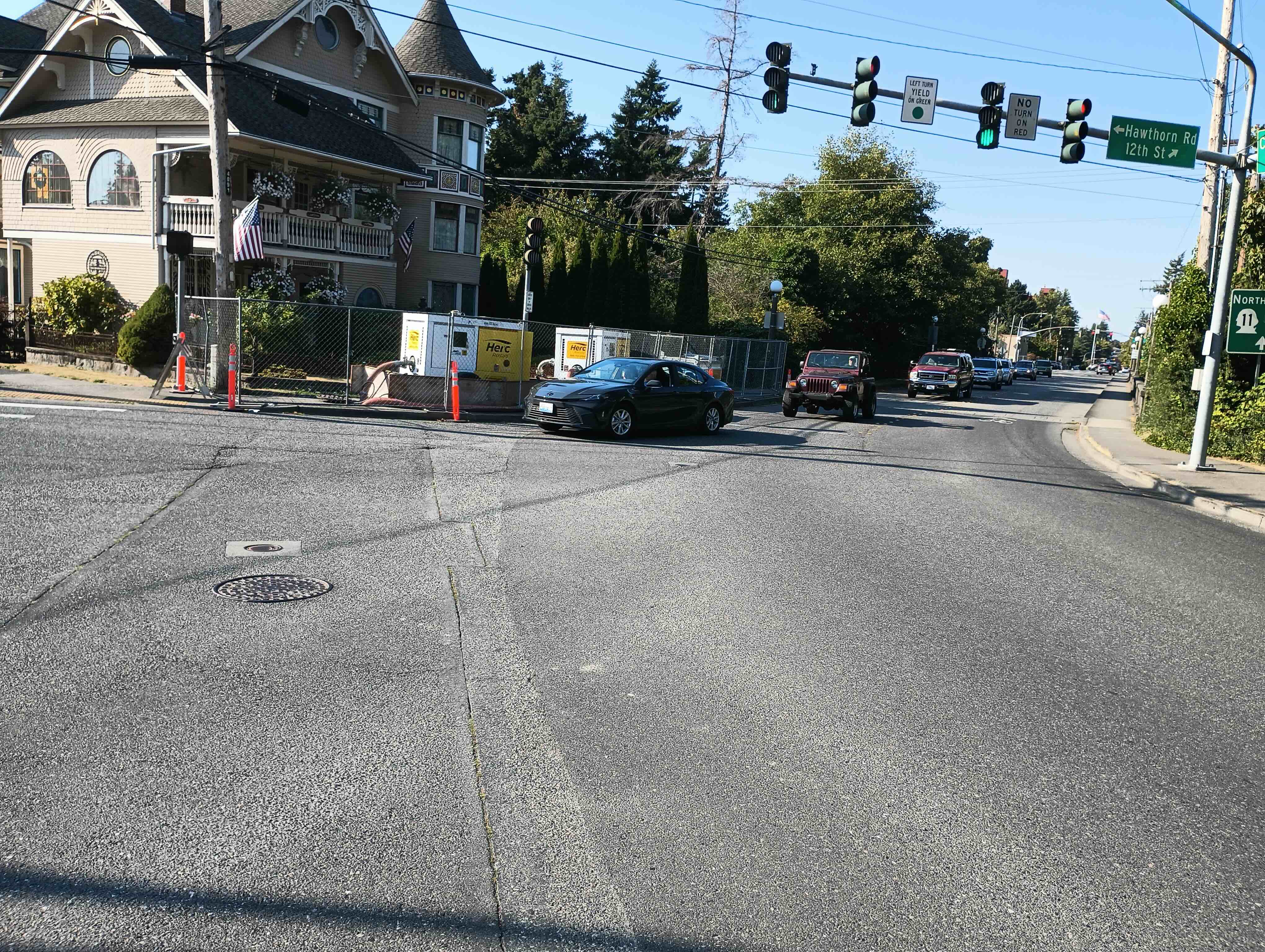

photo by Preston L. Schiller

A vital Fairhaven Commercial District sidewalk in front of the Peoples Bank (12th Street construction) has been fenced and blocked for several months between Mambo Italiano’s entrance and an important bus stop and entry drive to Fairhaven Haggen’s. Pylons against fence would not provide much pedestrian protection even if they were out a couple of feet into the traffic lane.

Blocked Sidewalks

Even where sidewalks are provided, they may not always be usable. Bellingham, like many other cities, often allows abutting construction activity to temporarily close sidewalks. According to city data, which may be somewhat incomplete, between 2023 and 2025 there were 84 sidewalk closures permitted with only two requiring protective scaffolding over the walkway.

In principal, the contractor is supposed to provide a safe adjacent walkway, such as using easily moved traffic cones or flimsy pylons to prevent motor vehicles from infringing upon the temporary walkway. In reality, there may not be any space, such as a parking lane or extra traffic lane width, into which the temporary sidewalk can be placed. In such cases, pedestrians will be directed, with code approval, to cross at the nearest intersection, often at some distance, and continue walking to the next intersection before crossing back to the side where they were originally walking. Rarely is such an inconvenience leveled upon motorists. One also needs to ask the question of “how temporary is temporary?”

The photos show that a few of the “temporary” closures have been in place for many months, even while construction has, in some cases, been suspended or, mysteriously, never appeared — as is the case with the months long blockage of the vital 12th Street bridge west sidewalk between Old Fairhaven Parkway and Cowgill Avenue serving both nearby neighborhoods and the Fairhaven Middle School. It is unclear whether the same departments issuing these permits are following these matters with inspections that might limit or end such blockages. While city code allows the use of scaffolding-supported covers overhead of sidewalks abutting construction in order to maintain pedestrian safety and continuity of the walkway, it does not seem to be used much.

Source: https://scaffolding.ca/experience/overhead-protection-landing-platforms/

Overhead scaffolding can keep sidewalks open while protecting pedestrians.

Traffic, Street Design and Intersections

Even where sufficient sidewalks are provided on both sides of a street, as in the main downtown north-south streets such as State and Forest, walking may be challenging. These streets have unusually long blocks built originally to accommodate the much anticipated arrival of railways, which needed long blocks for loading and unloading. The railways did arrive, as evidenced by the aptly named Railroad Avenue, but, even long after they moved to another route, the long blocks and very wide streets remained. These blocks may have a right-of-way (ROW) width up to 200 feet. In decades past, such width was put to “good use” by the city for excessive traffic and parking lanes.

Fairhaven and Downtown Bellingham Saved

After the city’s 1950’s best minds failed in their dream of routing I-5, then in its planning stages, down Old Fairhaven Parkway (SR11) to a large interchange at 12th Street and Harris Avenue (aiming to revitalize that area after fire destroyed the cannery that spanned what is now an estuary along Harris Ave.) then along the waterfront to another large interchange downtown to serve the Georgia-Pacific (G-P) pulp mill and then destructively traversing downtown and a number of neighborhoods, the question of how best to now accommodate growing downtown traffic emerged.

Since the shift-change traffic at G-P led to a few minutes of traffic congestion in the downtown core, the best minds decided that creating a one-way street grid was the solution. One way streets generally lead to a faster traffic flow which was seen as a good outcome. Thus, most downtown streets became three traffic lanes plus parking lanes. Multi-lane one way streets add to motorist danger as well as pedestrian danger as they encourage excessive lane switching and higher speeds than are desirable. Widely distanced intersections along one-way blocks also inconvenience cycling as well as walking.

To the city’s great credit, it belatedly recognized the folly of some aspects of this strategy, and, in recent years, has begun to reduce the number of lanes in downtown and converting some of that space to cycle lanes as well as widening sidewalks at intersections (bulb-outs) to allow a shorter crossing for pedestrians. These accompanied some welcome changes in transportation thinking and standards. Still more can be done to make walking easier on such streets, such as mid-block crossings. Pedestrian-activated signals could be introduced on these long blocks, and, where possible, these could connect mid-block walkways between blocks which would facilitate both shorter walking and cycling distances — especially where grades add additional effort to such trips. Reverting one-way streets to two-way is likely never to happen.

Sidewalks Necessary but Not Sufficient

Even where sidewalks are provided, pedestrians can face considerable challenges when they need to cross the street. In residential streets, residents often expect to be able to cross streets wherever it is convenient to access a friend or service rather than going to an out-of-the-way intersection to cross and backtracking. Traffic density can be an important factor in shaping whether such convenience is feasible. Convenient crossing is supportive of maintaining friendships, neighborly engagement and fostering local services. Urban geographer Donald Appleyard, whose son Bruce has followed in his footsteps, updated his father’s classical “Street Livability Study” of how traffic levels influenced the density of cross-street activity. As traffic levels rose, cross-street activity fell. Even without necessarily killing pedestrians, traffic was killing pedestrianism and livability.

Intersections as Hazardous to Pedestrians

Since pedestrians need to cross streets — and even motorists sometimes walk from their cars or cross a street to a nearby destination, there needs to be more done to improve intersections for pedestrian (and cyclist safety). Urban Geography professor Barry Wellar, now retired from the University of Ottawa (Ontario, Canada), has studied the issue of pedestrian intersection safety. (See Wellar in references.) The President Jimmy Carter-era regulation change allowing motor vehicles to turn right on red was introduced in the United States as well as Canada, aiming to reduce motor vehicle emissions by “keeping traffic moving” and reducing engine idling. It has not proven to do such, and, as internationally renowned researchers Peter Newman and Jeffrey Kenworthy (see references) have found, it might actually increase traffic and pollution. Besides, right turn on red is also a great way to reduce the population of pedestrians and cyclists. Most intersections, especially on traffic busy streets, are simply too complex in several ways to protect or encourage walking. There are simply too many complicated vehicular movements and accommodations including long wait times before receiving a “walk” signal — which can sometimes be too short for pedestrian comfort, widened roadways to accommodate more traffic, signalized turn lanes, lack of a safe way to pause midway across the street, etc.

Again, to its credit, the City of Bellingham has been moving to create more widening of sidewalks at intersections (“bulbouts”), add “pedestrian refuges” (protected islands separating directional traffic midway across the street), and lengthening signal walk times to allow for slower persons and those using mobility assistance devices to cross safely, and added pedestrian-activated signals along some streets. But progress is slow in correcting the preponderance of undesirable past practices.

No Sidewalks and Potential of Shared Streets

The City of Seattle has in recent years been addressing some of the problems of streets without sidewalks through a “Complete Streets” program (see references) that works with residents to create safe pedestrian passages, usually along road shoulders and often buffered from traffic by rain gardens, plantings, etc. Seattle may have decided that even more permission in State of Washington law was needed to protect pedestrians and cyclists from traffic. Seattle appears to have been a major driver in the recent passage of “Shared Streets” SB 5595 along with significant support from a few key jurisdictions, such as Bellingham’s 42nd.

This law allows municipalities to establish certain residential streets as shared streets, so that “Vehicular traffic traveling along a shared street shall yield the right-of-way to any pedestrian, bicyclist, or operator of a micromobility device on the shared street. A bicyclist or operator of a micromobility device shall yield the right-of-way to any pedestrian on a shared street.” SB 5595 also allows “Local authorities in their respective jurisdictions may establish a maximum speed limit of 20 miles per hour on a nonarterial highway or part of a nonarterial highway or a maximum speed limit of 10 miles per hour on a shared street …”

An excellent analysis of SB 5595 has been published in a recent edition of The Urbanist periodical by Seattle Greenways advocate Mark Ostrow (see references).

In addition to adding the provisions of SB 5595 to its portfolio of pedestrian and cyclist safety measures, the good news for residents along streets without sidewalks is that there are many other ways that the City of Bellingham and neighborhoods can do to slow traffic and increase safety for all street users, including those shameless four-legged jaywalkers such as deer, raccoons, coyotes, bobcats, and lonely cougars.

Shared Streets in Fairhaven

The southwestern Fairhaven residential neighborhood, bounded by 4th and10th streets and Harris and Cowgill avenues, appears to be a prime candidate for a shared street designation. In the 1970s and 1980s, its portion of Donovan Street was becoming a speedway for residents of an adjacent neighborhood who wanted to save a few seconds on a trip to and from their residences — even though a more appropriate route was available nearby.

By the 1980s, the neighborhood had “enuf ” of this dangerous cut-through rat-running phenomenon and feared it would only worsen with the imminent development of the ferry terminal and train and bus terminal (Fairhaven Station) at the foot of Harris Avenue. Led by, among others, neighbor Paul Schissler, a professionally trained planner, neighbors united in a successful effort to persuade the city and the Port of Bellingham to draft a legally binding agreement that would protect the neighborhood as well as some of its natural environment — such as Padden Creek.

And, according to Schissler, “in 1994, alarmed by the Public Works Department’s plan to route truck traffic to the Harris Avenue port facility by way of Donovan Avenue, the neighborhood organization, “Fairhaven Neighbors” (FN), objected and pushed the city to sign a second agreement with FN, which described a berm, pedestrian access, and other elements in a revised design of the new truck route.

The berm went in, and cut through speeding traffic greatly diminished. Resident motorists, including the annual crop of new college student renters, have learned to slow down and share the streets. Subsequent years have seen these neighborhood streets shared with a variety of users, persons walking, jogging or cycling for pleasure or purpose, children to and from school or school buses, dog walkers, persons walking kayak trailers down to the launch area, and an array of wildlife. Some of these users, including wildlife, appear to be coming from adjacent neighborhoods where such activities are not as safe or pleasant. Sometimes walking groups from the other end of Bellingham motor over to enjoy a pleasant, quiet, and safe stroll.

Despite its mostly successful efforts to protect itself from speeding and cut-through traffic, including oft-ignored signage restricting large trucks, and its efforts to promote a culture of street civility, the neighborhood is still burdened by excessive cut-through, occasionally speeding, traffic. According to Bill Liddicoet, who heads the Fairhaven Neighbors association, “(M)y neighbors and I are excited by the potential SB 5595 offers us to realize a much cherished goal: making the streets of our neighborhood calmer, safer, and a more congenial environment for pedestrians, cyclists and motorists alike.” Perhaps the City of Bellingham could further Fairhaven’s efforts and ambitions by making it the first designated shared streets neighborhood?

What if a Street Cannot Be Shared?

If the neighborhood without sidewalks has streets going through it that are busy with traffic, and, if calming and slowing traffic is not a viable option, then that street needs to be studied for applications of other measures, such as protected shoulders or protected walkways such as those recommended in Seattle’s Complete Streets and in some City of Bellingham options that could discourage speeding, cut-through traffic and excessive volumes of traffic.

Extremely complicated and dangerous intersections, such as the “star intersection” where 12th Street, Chuckanut Drive, Parkridge Road, Hawthorne Road and Cowgill Avenue intersect, abutting Fairhaven Middle School, should be studied for potential redesign and the prompt addition of pedestrian protective infrastructure — hopefully before a student is a crash victim.

Conclusion

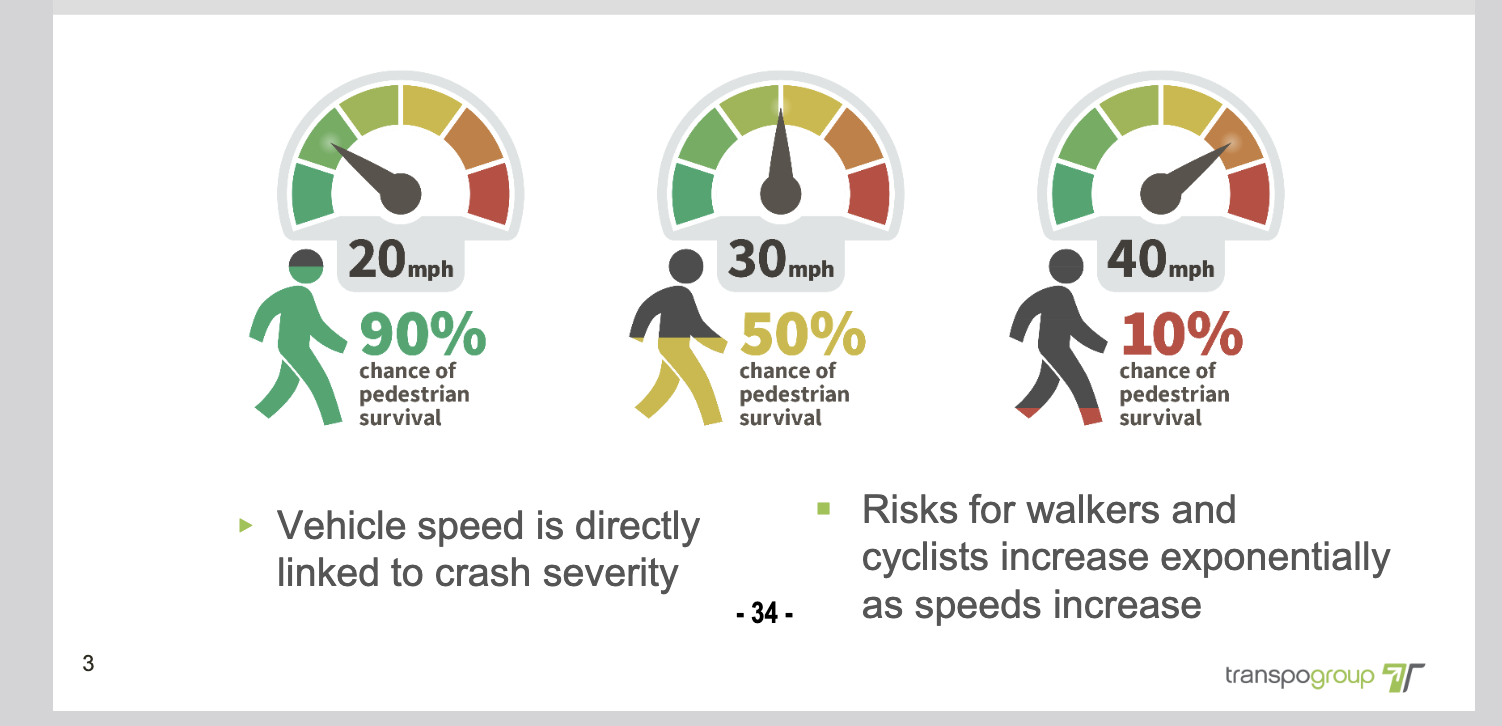

- The City of Bellingham and its Public Works Department have made some excellent proposals in its recent “Citywide Speed Limit Setting Policy,” which presents much valuable data and concrete proposals, as well as in its 2024 “Bellingham Pedestrian Master Plan.” There were several important findings in the most recent report, indicating that, despite the city’s efforts:

— Between 2020 and 2024: Fatal and serious injury crashes continue to occur;

— 40 percent of fatal and serious injury crashes involve a cyclist or pedestrian;

— 86 percent of serious/fatal crashes were on roadways with speed limits above 25 mph;

— At a vehicular speed of 20 mph, there was a 90 percent chance of pedestrian survival.

The speed limit proposals were presented to the City of Bellingham’s Transportation Commission on Sept. 9, and to the Traffic Safety Committee on Sept. 22, 2025. They will be presented to the City Council on October 6. Interested citizens should check the city’s calendar about this and future considerations of these proposals. Many residents might want to communicate to the City Council and mayor about their desire to lower speed limits even more than this report proposes and direct staff accelerate their review of SB 5595. - Each of these welcome Public Works efforts might have been strengthened by the participation of the city’s Planning Department; pedestrian safety and amenity is, at least, partly a function of the urban design and the built landscape — not just of streets and sidewalks. Perhaps a joint Public Works/ Planning effort could be undertaken in the future?

- The City of Bellingham deserves credit for improving the situation for pedestrians and cyclists in recent years, especially in some of its older, more densely populated neighborhoods. But one has to wonder whether significant levels of walking and cycling are ever likely to be attained in some of the lower density and recently annexed areas. At the very least, the city should stop sprawling into such areas, but, rather, pay more attention to making existing neighborhoods more amenable.

- The city can further pedestrian safety and comfort in the near term by reviewing its policies and practices involving “temporary” (sometimes everlasting?) sidewalk closures and offer better alternatives to forcing persons to cross and re-cross streets. Use of scaffolding-supported overhead protective platforms, without closing a sidewalk, should be one of the first, rather than last, considerations in such permitting.

- When an important walkway or path is being closed due to construction, and pedestrian and cycling traffic must be diverted, as will be the case when the much-used trail between Mill Avenue and the Douglas Avenue – 10th Street intersection, an important route connecting the Fairhaven Commercial District and Boulevard Park, a protected pedestrian passage needs to be provided — not just a marking of a space with flimsy pylons.

- There can be more and better enforcement of pedestrian and cyclist protections by law enforcement; is it time to reopen discussion of traffic cameras? Perhaps it is time to discuss whether the seemingly large amount of $10 million of the Transportation Benefit District (TBD) is sufficient or not for addressing the needs of pedestrian improvements.

As responsible and caring citizens , we need to acknowledge that the motor vehicle can be, among other uses, a weapon of mass destruction; the menacing, maiming, and killing of pedestrians (and cyclists) should be treated as seriously as as an assault involving a gun, club, or knife. Bellingham’s law enforcement is slowly moving in that direction when there is a high profile killing of a pedestrian or cyclist, but much more needs to be done.

Perhaps it is time for Mayor Lund and the Bellingham City Council to accelerate their reconsideration of speed limits to include shared streets (as allowed in SB 5595) and reduce speed limits along most Bellingham streets even beyond what is currently under consideration? The City of Bellingham has been given a powerful tool, SB 5595 “Shared Streets,” to add to its toolbox of traffic calming and street safety tools. One can only hope that it will be wisely and appropriately put to meaningful use.

At least one neighborhood, the southwest Fairhaven residential area, appears interested in considering whether to volunteer itself as a model. Meanwhile, keep on walking and watch out for the traffic.

The author thanks Bellingham’s Public Works staff for furnishing valuable information; views expressed are those of the author.

_____________________________________

Preston L. Schiller, Ph.D. is an advocate for streets that are safer for walking and cycling, as well as more and better transit. He is a veteran of many transportation and environmental reform efforts at federal, state and local levels. He is the co-author of “An Introduction to Sustainable Transportation: Policy, Planning and Implementation,” Routledge, 2018 (2nd edition) He has written over 24 articles for Whatcom Watch, from coal trains to transit planning and trails, beginning with its early years.

References

- Bruce Appleyard, “Livable Streets Revisited,” Planetizen, Feb. 26, 2023 — https://www.planetizen.com/features/121869-livable-streets-revisited

- Barry Wellar — https://wellar.ca/wellarconsulting/home.html

- City of Bellingham: 2010, 2020: Transportation Benefit District (TBD)

- City of Bellingham, 2024: “Pedestrian Master Plan” — https://cob.org/wp-content/uploads/2024_11_25_Bellingham-Pedestrian-Plan-Master-Plan_v6.pdf

- City of Bellingham, 2025: “Citywide Speed Limit Setting Policy” presentation to Transportation Commission, Sept. 9, 2025

— https://meetings.cob.org/Documents/DownloadFileBytes/Transportation_Commission_3704_Agenda_Packet_9_9_2025_6_00_00_PM.pdf?documentType=5&meetingId=3704&isAttachment=true - City of Seattle: “Complete Streets” program — https://www.seattle.gov/transportation/projectsand-programs/programs/urban-design-program/complete-streets-in-seattle

- Mark Ostrow, “Governor Signs Washington’s First-in-the-Nation Shared Streets Law” — https://www.theurbanist.org/2025/05/19/governor-signs-washingtons-first-in-the-nation-shared-streetslaw/

- Newman, P. and Kenworthy, J. (2015) “The End of Automobile Dependence: How Cities Are Moving Away from Car-Based Planning,” Island Press, Washington, DC.

- SB 5595 — https://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2025-26/Pdf/Bills/Senate%20Passed%20Legislature/5595.PL.pdf?q=20250920102517

- Scaffolding — https://scaffolding.ca/experience/overhead-protection-landing-platforms/

- Preston L. Schiller and Jeffrey R. Kenworthy, 2018, “An Introduction to Sustainable Transportation: Policy, Planning and Implementation,” Routledge, (2nd edition)

- Dan Zukowski, “Right turns on red puts pedestrians at risk, Mineta study says” — https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/news/right-turns-on-red-light-put-pedestrians-at-risk-mineta-study/738332/