Beaks and Bills

by Joe Meche

After a tumultuous 2025, we carefully leap into 2026 with dreams of a better year ahead … in every way. January is the time of year for making and breaking resolutions, to which a wise man (a comedian) once said … don’t make resolutions that are unattainable … keep them simple. He went further to suggest things like getting a haircut, taking a walk, etc. The message is: keep it simple. I’ve found in my own life that simplicity is the way to go, all things considered. That’s why I’m planning to lighten my load when we head to the Big Island of Hawaii in February.

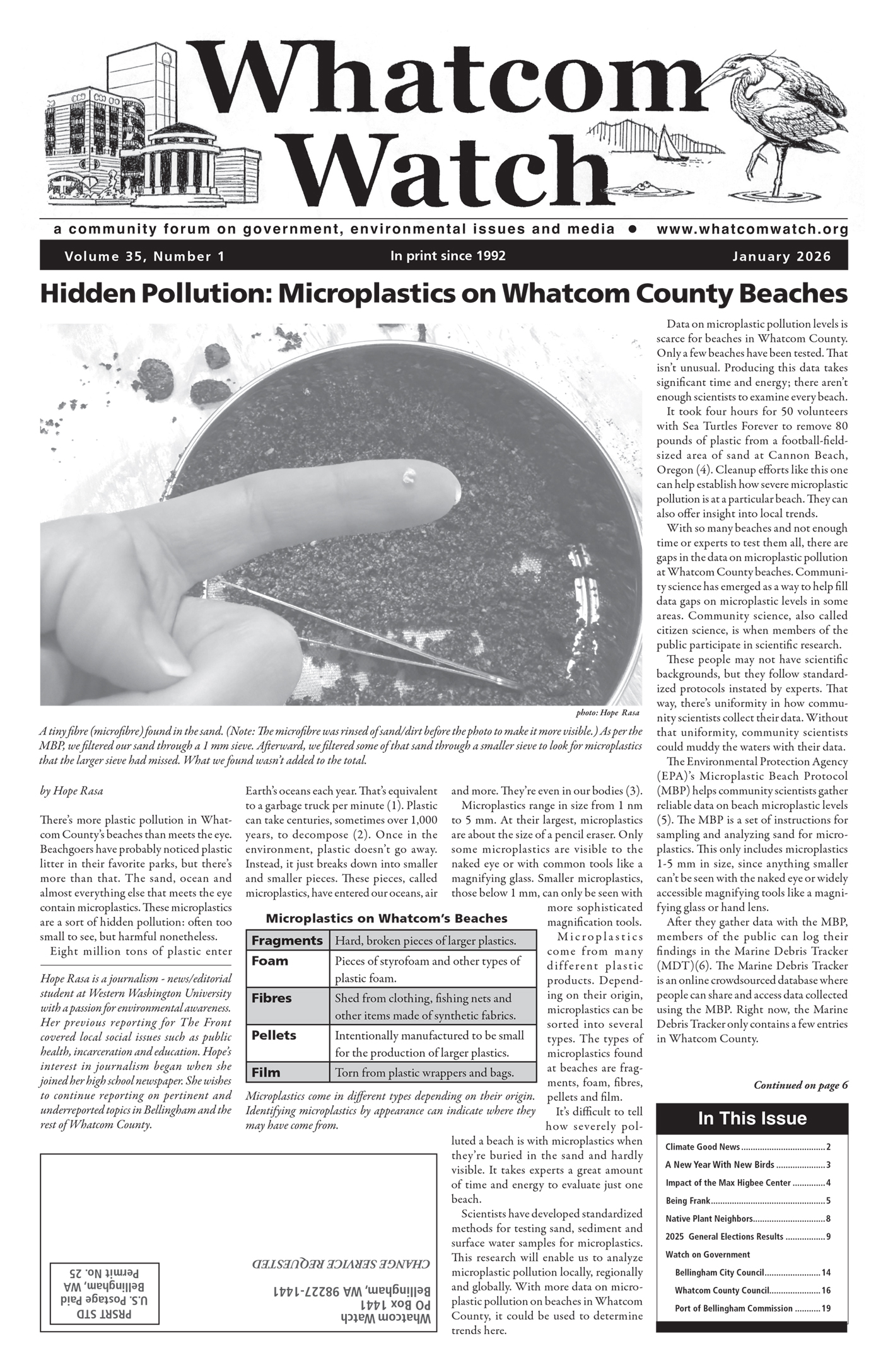

photo: Joe Meche

Bonaparte’s gull

Further to the title of this column, the new birds we’re seeing aren’t necessarily new to us. However, for avid birders, the beginning of a new year means starting a new list for all the birds you hope to see from January 1 to December 31. The first day of the year can be the beginning of your own version of a Big Year and can be a significant start considering all the new birds you’ll see right off the bat … using this concept. It’s easy to understand, and employ but persistence will be the key. Along with all this fun is the little known game of “first bird of the year” or FOY. These are just a couple of the games that we play, so if you know a birdwatcher, be gentle as you try to understand the obvious addiction/affliction.

As the Whatcom County compiler for the ongoing Birds of Washington census project, I have a ready handle on what’s being seen locally. All I need to do to add to my personal sightings is to log in to the new delight of some birders … eBird! I see eBirders in the field with their phones to their faces adding their sightings to the growing list that other like-minded individuals posted. I’m happy for them but I guess I don’t get it. Are the days gone by when you’d simply pack your binoculars and a lunch to spend time outdoors?

In addition, on first Saturdays from October through April, I conduct bird counts at three separate locations at the Semiahmoo Spit for the Puget Sound Seabird Survey. This past spring, I conducted wetland bird surveys for the Puget Sound Bird Observatory. These are two examples of the citizen science efforts that are ongoing to keep track of birds in specific locations during specific times of year in specific habitat areas. Seems we want to stay on top of bird numbers and movements throughout the year and across the continent.

And lest I forget, another Christmas Bird Count (CBC) will have come and gone since last we met. The premiere example of citizen science started in 1900 with a couple dozen observers spread out across the country. Today’s CBC boasts over 50,000 participants in more than 1,800 locations, most of which are in the United States and Canada. The CBC has been a mainstay in the collection of data pertaining to populations of wintering birds. A mirror count in May contributes similar data that reflects migratory bird trends in springtime.

In the overall scheme of things, it appears that humans have evolved into a species that wants to keep an eye on other species that share the planet. Reaching back in time, we owe it all to Carl Linneaus, the Swedish biologist and physician who is also known as the father of modern taxonomy (the scientific study of naming, defining, and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics). Linneaus’ system of binomial nomenclature utilized Latin names and applied to all organisms. This eventually gave rise to the need for common names, especially in the matter of birds … there were so many!

It would be a bit laborious to have to make note of a Turdus migratorious instead of just pointing out a robin, so common bird names for common folks evolved. The earliest English bird names came from the original German names in first millennium CE. Many of the early bird names in Old English texts are easily linked with the common names that we use. It comes as no surprise that, as the English language changed, so did bird names. For various reasons, the governing body of bird names in North America, the American Ornithological Society (AOS), elects to change the name of a species now and then. This frequently leads to initial confusion and even dissension far and wide.

Good examples of name changes affected us in the Fourth Corner with two common species … the long-tailed duck and the short-billed gull. The long-tailed was known for years as an oldsquaw, but the political correctness movement felt that was demeaning, even though the origin of that name fit perfectly with their vocalizations. The short-billed gull was formerly known as the mew gull due to its catlike calls. The name was changed by the AOS to more accurately address geographical populations. Either way, it was almost like adding two new birds to our lists.

When it comes to learning about birds there was no better inspiration or teacher than Roger Tory Peterson. His “A Field Guide to the Birds” debuted in 1934, and the public was so obviously prepared for such a guide that the first printing sold out in one week. The simplified text and his drawings were far more enjoyable than any textbook and offered a common ground for both amateur birders and scientists.

This guide and all the ensuing editions inspired a large environmental movement that continues to this day. The more you know about birds, the more you can appreciate them and their way of life.

I have done classes and presentations here and there that focus on the Peterson System of Bird Identification (the title of my own Power Points). The genius of his system lies in first observing the bird and then looking at things like relative size, location, and behavior. Later editions began to include range maps to make sure that what you’re seeing fits into where you are. No matter your level of expertise or interest, the common link to all these counts and censuses is knowledge of the names of the birds you’re seeing and counting. Some have expressed difficulty with learning the names, but, as it is with so many other pursuits, hands-on practice is required for whatever level you wish to reach.

As you read this and 2026 begins, add appropriate layers and spend time in the outdoors honing your skills in field identification. On my last census at Semiahmoo, it was obvious to me that our usual wintering birds were on site. Common loon numbers are building and a small flock of Bonaparte’s gulls was feeding between Tongue Point and Blaine harbor.

___________________________________

Joe Meche is a past president of the North Cascades Audubon Society and was a member of the board of directors for 20 years. He has been watching birds for more than 70 years and photographing birds and landscapes for more than 50 years. He has written over 250 columns for Whatcom Watch.