by Hope Rasa

There’s more plastic pollution in Whatcom County’s beaches than meets the eye. Beachgoers have probably noticed plastic litter in their favorite parks, but there’s more than that. The sand, ocean and almost everything else that meets the eye contain microplastics. These microplastics are a sort of hidden pollution: often too small to see, but harmful nonetheless.

Detail of photo below

Eight million tons of plastic enter Earth’s oceans each year. That’s equivalent to a garbage truck per minute (1). Plastic can take centuries, sometimes over 1,000 years, to decompose (2). Once in the environment, plastic doesn’t go away. Instead, it just breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces. These pieces, called microplastics, have entered our oceans, air and more. They’re even in our bodies (3).

Microplastics range in size from 1 nm to 5 mm. At their largest, microplastics are about the size of a pencil eraser. Only some microplastics are visible to the naked eye or with common tools like a magnifying glass. Smaller microplastics, those below 1 mm, can only be seen with more sophisticated magnification tools.

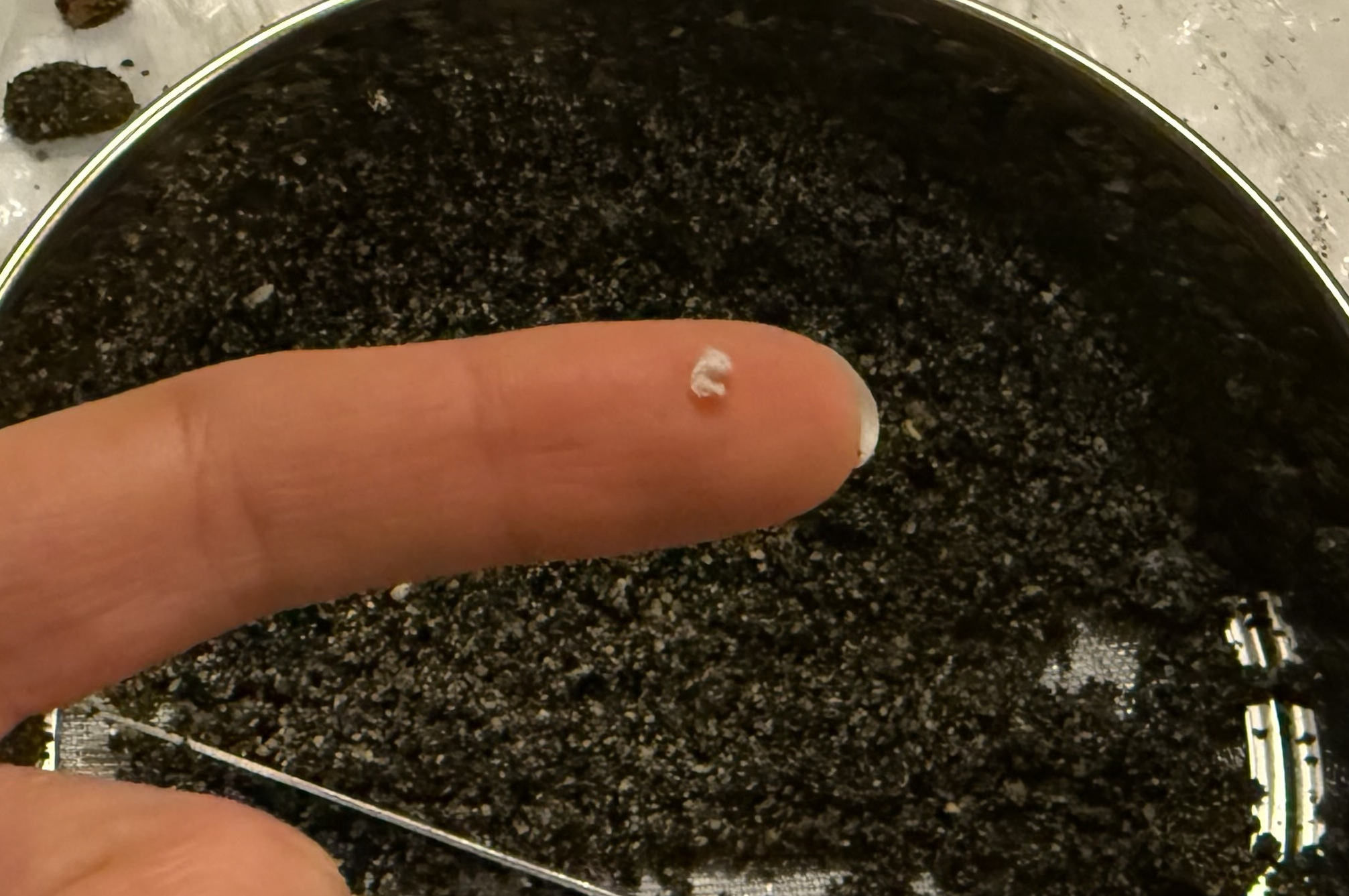

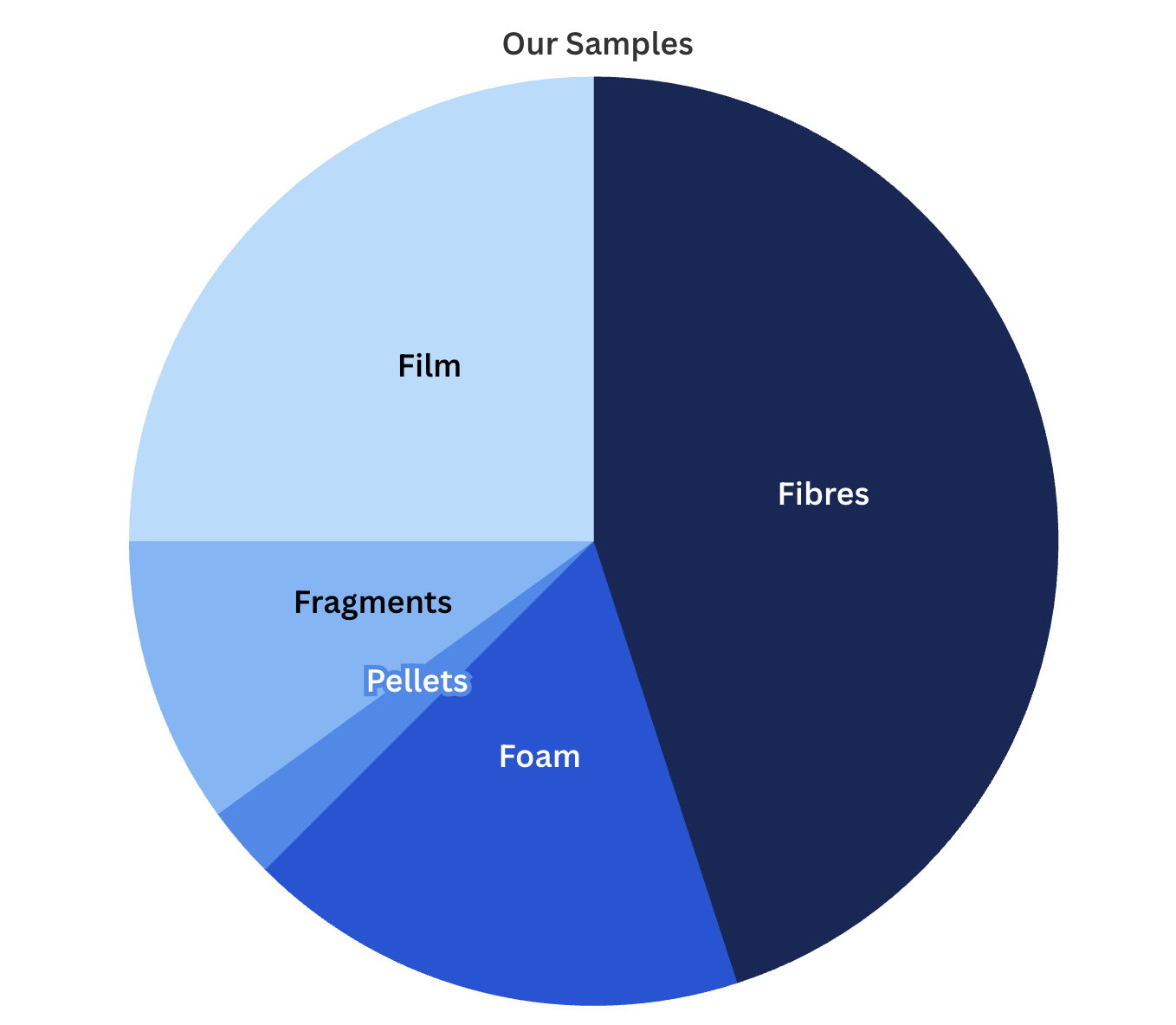

Microplastics come from many different plastic products. Depending on their origin, microplastics can be sorted into several types. The types of microplastics found at beaches are fragments, foam, fibres, pellets and film.

Microplastics come in different types depending on their origin. Identifying microplastics by appearance can indicate where they may have come from.

It’s difficult to tell how severely polluted a beach is with microplastics when they’re buried in the sand and hardly visible. It takes experts a great amount of time and energy to evaluate just one beach.

Scientists have developed standardized methods for testing sand, sediment and surface water samples for microplastics. This research will enable us to analyze microplastic pollution locally, regionally and globally. With more data on microplastic pollution on beaches in Whatcom County, it could be used to determine trends here.

Data on microplastic pollution levels is scarce for beaches in Whatcom County. Only a few beaches have been tested. That isn’t unusual. Producing this data takes significant time and energy; there aren’t enough scientists to examine every beach.

It took four hours for 50 volunteers with Sea Turtles Forever to remove 80 pounds of plastic from a football-fieldsized area of sand at Cannon Beach, Oregon (4). Cleanup efforts like this one can help establish how severe microplastic pollution is at a particular beach. They can also offer insight into local trends.

With so many beaches and not enough time or experts to test them all, there are gaps in the data on microplastic pollution at Whatcom County beaches. Community science has emerged as a way to help fill data gaps on microplastic levels in some areas. Community science, also called citizen science, is when members of the public participate in scientific research.

These people may not have scientific backgrounds, but they follow standardized protocols instated by experts. That way, there’s uniformity in how community scientists collect their data. Without that uniformity, community scientists could muddy the waters with their data.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Microplastic Beach Protocol (MBP) helps community scientists gather reliable data on beach microplastic levels (5). The MBP is a set of instructions for sampling and analyzing sand for microplastics. This only includes microplastics 1-5 mm in size, since anything smaller can’t be seen with the naked eye or widely accessible magnifying tools like a magnifying glass or hand lens.

After they gather data with the MBP, members of the public can log their findings in the Marine Debris Tracker (MDT)(6). The Marine Debris Tracker is an online crowdsourced database where people can share and access data collected using the MBP. Right now, the Marine Debris Tracker only contains a few entries in Whatcom County.

Understanding Microplastics

Plastic became mass-produced in the 1950s, and nearly 80 percent of plastic waste winds up in landfills or the environment. Even if humans stopped producing plastic today, plastic waste pollution would continue to be a problem for decades (7).

Some microplastics aren’t made from larger plastics that have broken down over time. Instead, they’re intentionally manufactured to be incredibly small. Companies melt tiny plastic pellets down into larger plastic products. Microbeads, another type of primary microplastic, are used in some cosmetic and hygiene products.

A portion of microplastics contains chemicals used to make them colorful or flexible. Microplastics release these chemicals into the water. Microplastics also behave like sponges in the water, absorbing harmful contaminants, like pesticides. Sealife can mistakenly eat these contaminated microplastics. This causes issues with reproduction, development and the ability to fight off diseases (8).

At the bottom of the ocean’s food chain, zooplankton eat microplastics. Then, bigger sea creatures eat the zooplankton. Eventually, microplastics work their way up the food chain to the food humans eat (8).

This isn’t the only way microplastics end up in the human body. Humans inadvertently eat, drink and inhale microplastics, as well as absorb them through our skin. Microplastics have been found in the heart, brain and other parts of the human body. They’ve also been found in placenta and breastmilk, showing babies are born already exposed to microplastics (9).

Early research shows microplastics may be linked to certain cancers, and likely harm respiratory, reproductive and digestive health (10). The study of microplastics is in its infancy; experts aren’t fully aware of their impacts on humans or the environment.

EPA’s Microplastic Beach Protocol

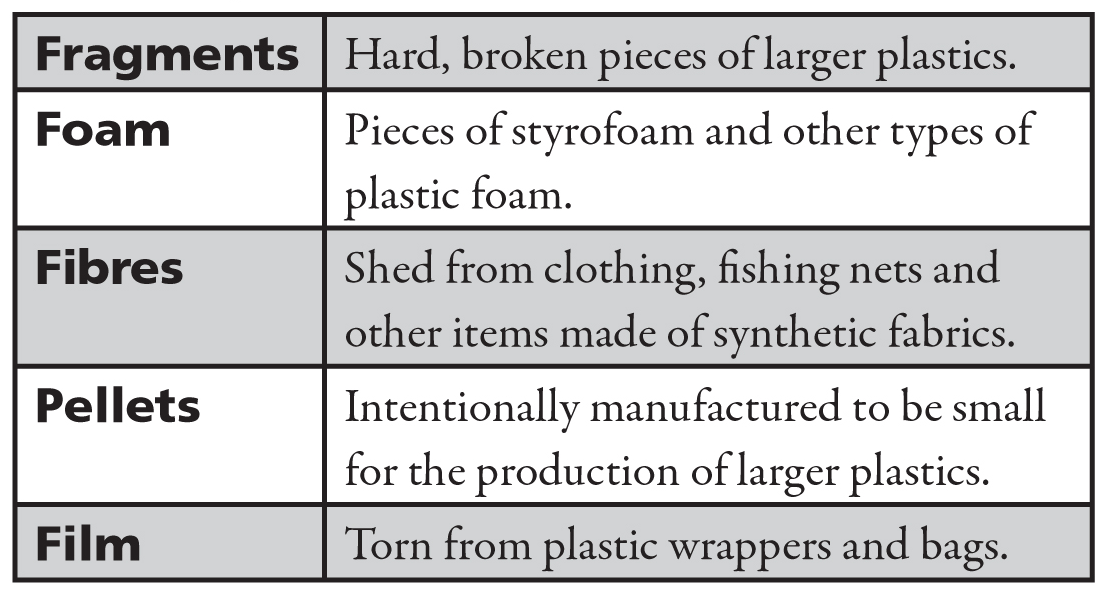

Following the MBP, three other people and I collected and analyzed sand samples from three beaches in Whatcom County: Little Squalicum Beach, Birch Bay State Park Beach and Locust Beach. This was for educational purposes; to inform others about the MBP’s existence and how it works.

Depending on your trip’s purpose and your group’s size, the MBP’s instructions for sampling are slightly different (5). We sampled the top layer of sand from 9 small (1 x 1 m) spots in a 100-meter area (about the size of a football field). The amount of sand we collected from each beach was about the size of a bag of flour.

A group using the MBP to determine a beach’s level of microplastic pollution would have collected more sand from a larger area of the beach than we did. Because our trip was educational, our sample size was smaller. Our findings aren’t necessarily reflective of the entire beach, just a piece of it.

Nearly all of the materials we needed for the MBP were household items. We only had to go out of our way to get two things: a sieve and a hand lens. Those we had no problem finding at a store.

After sampling, we brought the sand home. Then, we sieved through it and removed suspected microplastics, placing them in containers. Later that day, we inspected the containers. Some things we had collected weren’t actually plastic, just deceiving pieces of rock and seashell. We also collected a lot of plastic that was too large to be considered microplastics. With the microplastics, we sorted them by type (foam, film, fibres, pellets and fragments).

photo: Hope Rasa

A tiny fibre (microfibre) found in the sand. (Note: The microfibre was rinsed of sand/dirt before the photo to make it more visible.) As per the MBP, we filtered our sand through a 1 mm sieve. Afterward, we filtered some of that sand through a smaller sieve to look for microplastics that the larger sieve had missed. What we found wasn’t added to the total.

Find the full MBP, with all of the steps in full detail, online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-09/microplastic-beach-protocol_sept-2021.pdf.

What We Found

Total amounts of microplastics in our samples from each of the three beaches we visited, separated by type.

Data visualizations: Hope Rasa with Flourish

Pie chart depicting the ratio of different types of microplastics within our samples from all three beaches.

Overall, we found fewer microplastics than we expected. We anticipated finding more, given how prevalent microplastics are in the ocean as a whole (1).

However, what we found is similar to local cleanup efforts that also follow the MBP. In June of 2023, volunteers with RE Sources found 20 to 30 microplastics using the MBP at a small beach near Hilton Harbor Marina in Bellingham, Wash. (11) They also found fewer than they expected, according to Cascadia Daily News.

It’s good that groups keep finding fewer microplastics than expected on beaches in Whatcom County. However, it’s important to remember that the MBP isn’t entirely thorough, and microplastics are going uncounted. Searching for microplastics in the sand is like finding a needle in a haystack.

After a long enough time in nature, plastics can break down into pieces that resemble bits of seashell or rock. Pacific Northwest beaches are full of tiny, shiny rocks that could easily appear as plastic. We may have missed a few microplastics because they were well disguised.

The MBP includes a few methods for testing microplastics to see if that’s really what they are. We discovered some of the “microplastics” from our samples were in fact seashells or rocks. When we weren’t sure if something from our sample was a microplastic, the MBP instructed us to assume it wasn’t.

Larger studies show much higher rates of microplastics on beaches all over the United States. The National Parks Service, Clemson University and the NOAA Marine Debris Program sampled and examined sand from 37 national park beaches (12). Per 1 kg of sand (about the size of a bag of flour), researchers found an average of 21.3-221.3 microplastics. The amount of microplastics we found was barely on the lower end of that average.

That makes sense, considering the MBP is a much more achievable way to evaluate beach microplastic pollution. The MBP is designed to be accessible to the general public. The steps aren’t complicated, and the materials are easy to come by.

While the MBP doesn’t ensure finding all of the microplastics in a sample, it still allows for community scientists to characterize a beach’s level of microplastic pollution. This way, they can contribute to a growing database of knowledge about microplastic pollution in their area.

________________________________________

Hope Rasa is a journalism – news/editorial student at Western Washington University with a passion for environmental awareness. Her previous reporting for The Front covered local social issues such as public health, incarceration and education. Hope’s interest in journalism began when she joined her high school newspaper. She wishes to continue reporting on pertinent and under-reported topics in Bellingham and the rest of Whatcom County.

Article Links:

- Jambeck, J., et al. (2015, February 13). “Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean.” Science. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1260352

- Impacts of plastic pollution. (2025, May 15). United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/plastics/impacts-plastic-pollution

- Garthwaite, J. (2025, September 29). Tracking microplastics from sea to body. Stanford Report. https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2025/09/microplastics-environment-human-health-impacts-research

- Fisher, J. (2018, August 17). “How to clean sand: Volunteers take on microplastics at Oregon coast.”Oregon Public Broadcasting. https://www.opb.org/news/article/clean-sand-plastic-oregon-coast/

- EPA’s Environmental Beach Protocol: A community science protocol for sampling microplastic pollution. (2021, September). United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/system/#files/documents/2021-09/microplastic-beach-protocol_sept-2021.pdf

- Debris Tracker: An open data citizen science movement. Marine Debris Tracker. https://www.debristracker.org/

- Sheppard, L. (2021, February 16). ‘Plastics don’t ever go away’ — ISTC scientist John Scott studies impact of microplastics. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Prairie Research Institute. https://blogs.illinois.edu/view/7447/752802634

- “What are the impacts of microplastics?” (2024, July 8). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/tutorial-coastal/marine-debris/md04-sub-01.html

- Ragusa, A., Svelato, A., Santacroce, C., Catalano, P., Notarstefano, V., Carnevali, O., Papa, F., Rongioletti, M. C. A., Baiocco, F., Draghi, S., D’Amore, E., Rinaldo, D., Matta, M., & Giorgini, E. (2021). “Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta.” Environment International, 146, 106274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106274

- Savchuck, K. (2025, January 29). Microplastics and our health: What the science says. Stanford Medicine News Center. https://med.stanford.edu/news/insights/2025/01/microplastics-in-body-polluted-tiny-plastic-fragments.html

- Lerner, J. (2023, June 9). “Environmentalists find fewer microplastics ‘than expected’ on Bellingham beach.” Cascadia Daily News. https://www.cascadiadaily.com/2023/jun/09/environmentalists-find-fewer-microplastics-than-expected-on-bellingham-beach/

- Whitmire, S., Van Bloem, S. J., Toline, C. A. (2017, May 31). Quanti#fication of microplastics on National Park beaches. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Debris Program. https://marine-debris-site-s3fs.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publications-files/Quantification_of_Microplastics_on_National_Park_Beaches.