The Search for Integrity in the Conflict Over Cherry Point as a Coal Export Terminal

Today a statue of George Washington and Seneca leader Guyasuta, a guide to Washington and his party in 1753, overlooks Pittsburgh. Composite photo created by Lummi Nation Sovereignty and Treaty Protection Office.

Today a statue of George Washington and Seneca leader Guyasuta, a guide to Washington and his party in 1753, overlooks Pittsburgh. Composite photo created by Lummi Nation Sovereignty and Treaty Protection Office.

by Jewell Praying Wolf James, Lummi Indian Tribe

“The whites got together and talked until it made my heart feel dead … I saw the Great Father [the president] again and told him that I would not let the cattle, or the Railroad, pass over my land. Finally the Great Father told us that they wanted the land … and that if we did not give it up it might be bad for us, that they might put us in some other place.” (Pretty Eagle, Crow Nation, 1880)

Introduction

We are living in a fast-paced society and rarely take the time to reflect upon the truths behind the laws that govern us. We are, one and all, proud to be law-abiding citizens. We operate under the assumption that the law is just, reasonable, and fair, and that no person stands above it. But how many people understand — or have even been introduced to — the important role Native Americans played in the governance of the American Nation?

I hope through the medium of history to give voice to a silenced history. In this article we will move through time, from first contact between European-Americans and the indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere, in 1492, to the present conflict over Cherry Point. Along the way, I hope to inform the reader about some of the laws, political realities, and administrative procedures that benefit corporate interests more favorably than either tribal rights or the greater public good. Just as important, I hope to show how the general public can influence the final outcome of this search for integrity.

Key Events in United States — Native American Relations

1823 Johnson v. M’Intosh – first claim of discovery ruling

1832 Cherokee v. Georgia – ruling that Indians are like wards to the guardian

1855 Point Elliot Treaty defines agreement between US government and Pacific northwest Tribes

1859 Point Elliot Treaty proclaimed law of the land

1872 President Grant shrinks Lummi reservation land by Executive Order

1883 Religious Crimes Code bans religious freedom for Native Americans (unless Christian)

1923 Circular 1665 – banned Native American ceremonial dancing

1950 Last termination era – residential schools, forced relocations, extermination of tribalism

1955 Tee-Hit-Ton termination era case – all Indians declared to have been conquered

1970 Lummi refuse $58,000 offer for San Juan Islands and mainland Lummi home areas

1974 Boldt decision – reestablishes Native American treaty claims

1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act allows aboriginal ceremonies

1979 Lummi tribe closes commercial herring fishery for conservation purposes

1979 Supreme Court ruling on Boldt decision reaffirms rights to treaty fisheries

1988 Supreme Court strikes down American Indian Religious Freedom Act

2011 Pacific International Terminals illegally bulldozes and drills on GPT land

Part I

From Natural Law to National Law: The Growing Point

Over two hundred years ago, during the colonial period, Native Americans, in accordance with their sacred vision, pressed upon the Founding Fathers to unite the colonies and hold leadership accountable to the people they represented. The First Americans were important role-models for the development of the Constitution (1787-89). In 1987-89, the United States Congress, in Senate Concurrent Resolution 76 and House Concurrent Resolution 331, proclaimed that the Iroquois and Choctaws Confederacies were role-models for the Constitution. Students are rarely taught this history. Most Americans do not know that the Sons of Liberty worked closely with the Iroquois and Mohawks to learn how to be “First Americans” and to stand up united for their inherent rights of liberty and freedom, as one people that shall choose their leadership and hold them accountable. But to understand the full significance of this, we must first look back to the original foundation of the tribes’ relationships with the United States.1

Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas

Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas

We need to return to the time of Columbus and the life and work of Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas. In 1502, at the age of 18, this young man, whose family was known to Columbus, disembarked with Governor Ovando to the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic). He was on the first two military missions aimed at pacifying those Natives who remained on the island. In the end, and in short order, the brutality he witnessed in the treatment of the Native peoples inspired him to renounce his family’s holdings on the island and begin his life-long campaign to protect the Indians.

In 1550, at the request of Charles V of Spain, Las Casas debated his fellow Dominican Priest Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda. Sepúlveda argued that the Indians were “natural slaves” (an Aristotelian concept that posited that there are people who by their nature or lack of rational capacities are born to be ruled by others) and that it was therefore legitimate to reduce them to slavery or serfdom. In his frustration, Las Casas stated that it would be better to enslave the blacks of Africa than to enslave the Indians. He lived to regret this outburst as the African slave trade rapidly expanded into the Americas.

Las Casas claimed the Indians had a right to be self-determining and self-governing, and should not be conquered, enslaved, or have their property taken from them. He forcefully and persuasively argued the actions of the conquistadores were criminal and in violation of the laws of Christian Nations. Sepúlveda maintained that the “savage, heathen” Indians were best described as “like women are to men, like apes are to humans, like children are to adults.”2 Two hundred and fifty years later, in the nascent United States, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall ruled in Cherokee v. Georgia (1832) that the Indians “were like wards to the guardian.”3 He made Sepúlveda’s argument a principle of national law. The barbaric enslavement of Africans and the eventual shipment of 3.9 million human beings from Africa to the Americas were also justified, in part, on the basis of this presumed natural law. These are two sad and salient examples of how narrow, convergent, and self-serving theological, political, and economic interests translated into jural-legal orthodoxy and national laws moved from “discovery” into colonization. Ultimately, manifest destiny became the accompanying narrative to the formation of the United States.

The Daisy Chain of Legal Fictions

In Johnson v. M’Intosh, Supreme Court Chief Justice Marshall in 1823 gave birth to legal recognition of the “Discovery Doctrine” as a cornerstone to United States law. It proclaimed that “the first Christian Nation” to discover a territory, occupied or not, had superior right to it over and above other subsequent Christian nations making the same claim of discovery.4 It was a rule honored between nations to lessen the likelihood of war. It also proclaimed that the Indians had only the right of occupancy, not ownership, of their territory. This court decision gave birth to the next legal fiction: that the United States had conquered all the tribes they had encountered. The fiction of conquest extended west of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers and applied to tribal peoples who knew little or nothing about the United States. In 1955, this served as a precedent for yet another legal fiction in the Termination-Era case of Tee-Hit-Ton. In this case the Supreme Court justices, by adding their signatures to the opinion, ruled as conquered all the Indian Nations.5 Here you see the daisy chain of the legal fictions passing as truth and imposed on tribal peoples who had helped form—and have often fought and died for—the United States.

The presumption was that Indians were wards, despite the fact that the United States was negotiating (in ‘good faith’) treaties with the sovereign tribes to avoid wars the United States could not afford in either blood or treasure. This mythology grew in subsequent Supreme Court decisions. What is not well known is that Chief Justice Marshall had a conflicting vested interest in a land speculation company that sought to secure illegal title to Indian lands in the Northwest Territory (Ohio at the time). His ruling legitimized, solidified and protected his investment. He would later regret this decision, but the damage was done: it was too late to reverse his decision. He died before he had an opportunity to argue for the reversal of M’Intosh or for at least a narrowing of its legal significance.6

Into the Far West

It is all too common for history books to valorize American manifest destiny. It is taught to school children to narrate American exceptionalism and the greatness of popular governance. It is used to signify the idea of unfettered freedom of conscience and person, free trade, the egalitarian spirit, and mobility. This narrative fueled and justified the arrogance of those who were sent out by the President to negotiate treaties with the Indian Tribes as the United States expanded to the west.

The painting American Progress by John Gast (1872), an allegory of Manifest Destiny advancing the American settlers by horseback, train, covered wagon, and stagecoach across the prairies as Native Americans and animals flee. Credit: Picturing U.S. History.

The painting American Progress by John Gast (1872), an allegory of Manifest Destiny advancing the American settlers by horseback, train, covered wagon, and stagecoach across the prairies as Native Americans and animals flee. Credit: Picturing U.S. History.

The negotiators came west of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers into the Louisiana Territory, through the Great Plains, into the Far West and Northwest (Washington and Oregon Territories). They were borne by the conviction that the United States was destined to rule a “savage” continent. As Anthony Pagden described it, as the Euro-American vision of the world moved westward across North America, “so it moved also inexorably backwards.”7 This perception and conception was reflected in the debates of the 18th and 19th centuries when America was viewed as a continent in an “arrested state of development.” 8 In this frame of mind, the President’s men would unfairly, and with only a semblance of honesty and good faith, negotiate treaties with the tribes. Although the Courts recognize that the treaty negotiations were not often honorable, they have avoided review of the treaty proceedings and upheld treaties as a matter of principle, as the ‘Supreme Law of the Land’ under the Constitution.

Making Treaties, Breaking Promises

The treaties in the Northwest Territories were negotiated by Joel Palmer in Oregon Territory and Isaac Stevens in Washington Territory. These treaties covered the modern-day states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. The Treaty with the Omaha Indians was used as a template to structure the treaties in these territories, including the Point Elliot Treaty of 1855, which was ratified by the Senate and Proclaimed by the President in 1859 and became the “supreme law of the land” (Art. VI). These treaties were legal and political instruments that were used to permanently locate the Indians on reservations. They were one important part of the colonialization era of the American Indian (1850-1871).

Under the terms of the treaties, Native peoples, under extreme duress, ceded to the United States certain rights with the understanding that anything not given was reserved to them. This reserved rights doctrine is not an alien concept in the American experience. It was incorporated in the Constitution of the United States for the protection of the citizen and states (Articles 10 and 11 of the Bill of Rights). The problem is that the United States, and Washington state, took the rights of the treaty without honoring the commitments made to the Indians. The Indians were ordered to stay on the reservation as the settlers expanded into their aboriginal territories and secured titles to the lands — lands that were never purchased or paid for by the United States.

Lummi Reef Netting (ca. 1890). Photo: Lummi Nation Archive.

Lummi Reef Netting (ca. 1890). Photo: Lummi Nation Archive.

The Lummi were the first reef-net fishermen in the Pacific Northwest. This technology was spread amongst the tribes around the Salish Sea but was invented by the Lummi. It was introduced into other tribal communities by way of intermarriage between the tribal groups. The technology reflected the sacred balance between the male and female genders. It was a part of the duality, and of the sacredness of creation and sustainability. Those men that operated the reef nets had a duty to themselves and their families; but, in exchange for the sacred right to fish, they had to assure that every widow, woman, and child that did not have someone to care for them received enough salmon annually to sustain them. They did this in recognition that they only had a right to harvest if they respected the salmon as a gift to all the people. This is why the First Salmon Ceremony was so important to the Coast Salish Nations.

Lummi Reef Net Demonstration (ca. 1890). Photo: Lummi Nation Archive.

Lummi Reef Net Demonstration (ca. 1890). Photo: Lummi Nation Archive.

Throughout the San Juan Islands, as the salmon migrated into the Straits of Juan de Fuca, through the San Juan Islands, and back to the river systems, including the Fraser River, the tribal people practiced the First Salmon Ceremony. This ceremony was essential to harvesting any of the salmon runs. The salmon were the Children of Salmon Woman. Her children were a gift to us. We were obligated to honor their return. As the salmon passed through our fishing territory the First Salmon Ceremony was conducted, each in its turn. This process connected Cherry Point to all the other sites before and up to Point Roberts, into the Fraser River, in the ceremonial cycle. The people buried at Cherry Point were ancestral reef net fishermen who kept these ceremonies alive for each generation after them.

Lummi Reef Net Anchor. Photo: Lummi Nation Sovereignty and Treaty Protection Office.

Lummi Reef Net Anchor. Photo: Lummi Nation Sovereignty and Treaty Protection Office.

In the case of the territory of the Lummi Indians, the United States offered to pay $58,000 in the early 1970s for the San Juan Islands and mainland homeland areas in Whatcom County. When the Lummi refused this offer the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), as the tribe’s “guardian,” accepted the money on behalf of the tribe (their “wards”) and placed it in the U.S. Treasury. The BIA argued with the Lummi, saying the tribe could use this money to build a school, a hospital, or homes for their people. The Lummi response was to order the BIA off the reservation. After their unceremonious departure, the BIA made it clear that they would hold the money until the tribe “came to its senses.”

At the time of this “offer” the United States was still in the fever of the Termination era, conveniently terminating treaty duties and responsibilities owed to the tribes. During this most recent cycle of termination, which began in the early 1950s, the United States (through overt actions as well as subterfuge) sought to disband all tribes and exterminate tribalism. The BIA was busy relocating the individual Indians as well as whole families into major metropolitan areas to break apart their kinship ties and separate them from their collective tradition of tribalism.9 Adding insult to injury, the BIA was shamelessly paternalistic and accepted offers by non-Indians to buy Lummi land. The ultimate goal of the BIA, an agent and agency of the United States, was to make our exile permanent. Though they are the Bureau of Indian Affairs, their allegiance is first and foremost to the federal government, not the tribes. In other words, the United States attempted to pay itself to gain control of our lands. This action was as corrupt and unconscionable as the perverse application of the Discovery Doctrine in the M’Intosh decision and the twisted principle of wardship in the Cherokee ruling.

The Way Back to Xwe’chi’eXen (Cherry Point)

Around the time of the signing of the Treaty of Point Elliott, the Chief of the Lummi, Chow-it-soot, made clear his concerns about what is now known as Cherry Point. He reminded his people that this was one of their most important and ancient village sites. The Chief was adamant that this site was — and must remain — the northwest corner of the reservation. He reminded his people that it had been unlawfully taken from the Lummi and that the Lummi must get it back. Since that time, all of the Lummi Chiefs have directed Lummi leadership to get Cherry Point back into Lummi ownership and ensure its protection. It is, in the words of our current Hereditary Chief, Tsilixw (Bill James), the “home of the Ancient ones.” Its integrity must at all costs be respected and protected with its burial areas and ancient grave sites.

The relevant territorial and federal records have been buried deep in the federal archives to prevent the Lummi from re-acquiring this part of the original reservation. This story goes back to the white squatters along our eastern and northeastern reservation boundaries. We demanded the federal government remove the squatters from our reserved lands. Instead the government-appointed Farmer-in-Charge (a non-Indian married to a Lummi woman), asked the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to change the boundary to protect the squatters. President Grant, of course, complied with the request and unilaterally changed our boundaries in 1872 by a Presidential Executive Order. This Executive Order contravened federal law for only Congress can change the boundaries of an established treaty Indian reservation.

The aboriginal territory of the Lummi Nation which included the San Juan Islands, Cherry Point, and other coastal lands up to Point Roberts. The current Tribal lands are marked in red on the map, including a small property on Orcas Island at Madrona Point. Credit: Ann Nugent, History of Lummi Legal Action Against the United States (Bellingham: Lummi Historical Publications, 1980), 35.

These alienated reservation lands have never been returned to the Lummi people. We were required to move to and stay on the reservation once the treaty was ratified. Over time, significant portions of our reservation lands were sold to white buyers by the BIA despite the fact that the sales violated the treaties. Nor did the Lummi receive compensation for the sale of these reservation lands. These lands are neither lost to us nor forgotten.10

Part II

Introduction

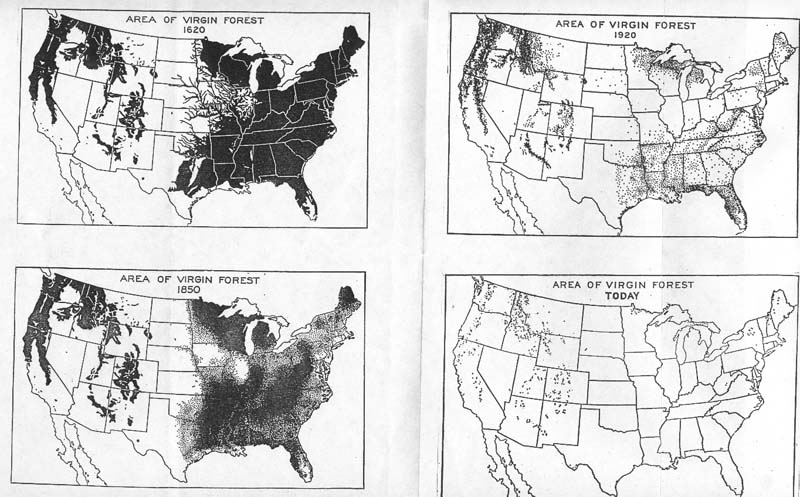

Deforestation of the United States since 1620 is almost complete. Even in 1920, very little virgin forest remained. Photo: O Ecotextiles.

Deforestation of the United States since 1620 is almost complete. Even in 1920, very little virgin forest remained. Photo: O Ecotextiles.

Following the signing of the treaty, our people watched as the aboriginal forests were cut down, the salmon were fished to near extinction, the rivers and streams were drained for agriculture and municipal needs, or dammed, and the animals were slaughtered by recreational hunters. Our sacred sites and cemeteries were desecrated, with our sacred artifacts and ancestral remains going to collectors or to universities for storage and study. We were not allowed to leave the reservation to fish, hunt or gather under the threat of prosecution by state or federal authorities. All during this time, the federal government, our “Trustee,” refused to protect our treaty rights against the State and its enforcers. Looking over this history, up to the present day, we ask the readers to stand with us and ask:

What About Those Promises…

…about Acting in a Moral and Ethical Manner…

The venality of the Department of War, which oversaw the BIA, stealthily taking back everything promised and allocated by Congress and the President to the Indians from 1789 to 1849, is well known to history. It was also apparent to Congress, which transferred Indian Affairs to the Department of the Interior. Sadly, but not surprisingly, they merely continued this practice from 1849 to 1872. In utter frustration, President Grant gave de facto jurisdiction over Indian Affairs to the churches believing they would act in a moral and ethical manner. This would usher in the shameful era of Boarding Schools, yet another growing point for transgenerational trauma still evident in tribal communities today.

The missionaries sent to live among the Native American communities were horrified by our traditional cultural practices and ceremonies they believed to be pagan in nature, immoral, and counter to government assimilation policies. The Religious Crimes Code of 1883 gave agency superintendents authority to use force or imprisonment to stop these religious and ceremonial practices. This religious persecution continued under Commissioner of Indian Affairs Charles Burke. In 1923 Commissioner Burke implemented the now infamous Circular 1665 that expanded upon the Religious Crimes Code and banned all forms of Native American ceremonial dancing.11

This institutional racism continued through the era of the civil rights movement. In 1988 the Supreme Court struck down the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978, an Act uniformly opposed by many of the Nation’s leading extraction industries — particularly the coal industry. The court concluded that the act was bad law and bad policy. Prior to this decision Native Americans were arrested for having eagle feathers in their regalia, arrested for their spiritual practices, were largely powerless in congress or the courts to prevent the destruction of ceremonial sites and areas, and were even prevented from having spiritual ceremonies in federal prisons. Also, they could not have peyote as their sacrament in the Native American Church, even though this ceremony dates back to 8000 B.C. In addition, tribes did not have the legal right to recover the bodies of their ancestors for reburial. In the 1990s, after intensive lobbying by the tribes, the legal rights of recovery and reburial were returned to the tribes under federal law.12

…about our Fishing Rights…

The state of Washington had been attempting to restrict fishing by tribes since 1889, the first year of statehood. When the state issued permits for non-Indian fish traps in the early-1900s, the Indians were driven from their fishing grounds by non-Indian interceptions of the salmon runs. If any Indians had a choice location for a fish trap, they were driven out by force of arms and left unprotected by state law. Washington enacted laws to restrict Indian fishing to within reservation boundaries. Decades later, the U.S. government finally intervened and helped the tribes sue the state of Washington, contending that the state could not regulate the fishing practices of Indians who signed treaties with the U.S. government; that it was the tribes who had been forced to cede their right to fish to non-Indian settlers, not the other way around. This was the U.S. v. Washington (“Boldt”) decision of 1974.

Five generations after the signing of the treaty, the 1979 Supreme Court’s ruling on the Boldt decision (Washington v. Washington State Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Association) reaffirmed tribes’ right to have their treaty fisheries, with up to 50 percent of what is referred to as the harvestable shares. However, by the mid-1970s the salmon stocks had been seriously depleted by the state licensed non-Indian fishing fleet. Some stocks collapsed to the point that they had to be listed under the Endangered Species Act.

An aerial map of Xwe’chi’eXen (Cherry Point). Credit: Google Maps.

In 1979, the Supreme Court decision also affirmed that the fishing tribes had the right to have the salmon habitat protected. The Court reasonably ruled that Indians had a treaty right not only to their share of the fish stocks, but also a right to dip their nets into the waters and not come up empty. This was, as feared by the state and corporations, the Indian veto power over future industrial development that might impact critical habitat of the salmon and other fish stocks.

On March 29, 2013, in accordance with the 1979 decision, District Court Judge Ricardo S. Martinez ordered the state to fix approximately 180 culverts on recreational lands by 2016 and 813 culverts under the Department of Transportation by 2030. In his ruling, Judge Martinez said the tribes have been harmed economically, socially, educationally, and culturally because of reduced salmon harvests caused by state barriers that prevent fish passage. He ruled that the state has the financial ability to accelerate the pace of its repairs over the next several years.

In 1979 the Lummi tribe, on its own initiative, sought closure for conservation purposes of the state and tribal commercial herring fishery that extended from the Lummi reservation, past Cherry Point to the Canadian border. The Cherry Point shoreline was a primary herring spawning habitat. The lucrative annual herring fishery was worth about $3 million per year to our treaty fishermen. This closure is still in effect 34 years later. Lummi tribal members have sacrificed over $100 million over that time in lost fishing income. This lost income represents our investment in restoration of the future resident herring population. In addition, the immediate area is good for crab fisheries and other stocks. We understand, honor and respect what needs to be done, and have sometimes sacrificed, to be true stewards of these resources. We consider it our sacred obligation or Xa Xalh Xechnging in our language. Unfortunately, at Cherry Point and elsewhere in the Salish Sea bioregion, this sacred obligation is seldom respected in any meaningful way by either the governments or by commercial and industrial interests. In a sense, Xwe’chi’eXen (Cherry Point) represents a challenge that is faced every day by each one of the American Indian tribes and Canadian First Nation Bands in Salish territory.13

The Lummi have usual and accustomed fishing grounds scattered throughout the San Juan Islands and on the mainland of Whatcom County up to the Canadian border. Not only were our (fishing) village sites located throughout the territory, but the associated burial grounds are located at these sites, as well. Among the most important of these cultural landscapes is Xwe’chi’eXen (Cherry Point).

…about our Sacred Obligation…

Xwe’chi’eXen (Cherry Point) was an important village site for our ancestors. This 3,500 year-old village site was where our inland relations travelled by canoe to visit their relatives’ villages to the north on the British Columbia mainland and to the west on Vancouver Island. There are nine Lummi kinship groups affiliated with Cherry Point. If we take those names as a starting point, 60 percent of modern-day Lummi have direct ancestral ties to Cherry Point. Their ancestors lived there for 175 generations and it is a final resting place of many of these ancestors.

Over the past several decades there have been numerous intrusive archaeological studies completed at this former village site. We were not asked to give our permission to conduct these archaeological studies. During the time of these studies, the non-Indians operated under the assumption it is appropriate to have their way with Indian graves and cemeteries. They were, after all, “professionals.” In the course of those studies, artifacts, and human remains were “recovered” and moved to Western Washington University. They have been stored there ever since. Can you imagine if this were your family’s ancestors in a box, on a shelf, in a university, and marked as “human remains”? This is all part and parcel of the legacy of institutionalized racism that permeates our relationship with portions of the non-Indian community. We are treated with respect when it is useful, then as brutes, savages, or children of a lesser God when we are not, and promises made to us are made only to be broken.

County Councilmember Carl Weimer was walking his dog one day at Cherry Point when he discovered unexpected activity in the nearby wetlands. To his great credit, he did the right thing and notified the proper authorities. As it turned out, Pacific International Terminals (PIT), acting true to its apparent character, authorized their contractors to bulldoze in what PIT knew to be a registered archaeological site. They bulldozed four miles of road and then sunk bore holes into the land. No permits were applied for or received, though they were perfectly aware they were needed. Incredibly, PIT makes the highly dubious claim that this was simply an oversight, not unlike their illegal activity in the wetlands of Cherry Point — supposedly something that simply “fell between the cracks.”

Some of the damage inflicted on the Lummi sacred ground at Cherry Point by the Gateway Pacific Terminal proponents’ exploratory excavations and drilling. Photo:Carl Weimer.

Some of the damage inflicted on the Lummi sacred ground at Cherry Point by the Gateway Pacific Terminal proponents’ exploratory excavations and drilling. Photo:Carl Weimer.

This illegal action served to help drain wetlands, a nuisance factor in the way of their plan for development. Applying for and fulfilling the requirements would cost time, and time is money and land is a “commodity.” So, they decided to get a head start and take a slap on the wrist. The same thing occurred in the archaeological site at Cherry Point. Rather than getting the permit they clearly knew was needed, they proceeded to move in their equipment, bore their holes, and get the data. It was a business decision and a calculated risk. The information is allowing them to proceed with their preliminary design for the project. Had they followed the law, a good deal of extra work would have to be done to ensure that the integrity of this ancient village site was not damaged. It was a wise business decision that can be defended, for a time, by their legion of lawyers. We believe Whatcom County Planning has given the impression of complicity in this, their proclamations of innocence notwithstanding.

More damage inflicted on the Lummi sacred ground at Cherry Point by the Gateway Pacific Terminal proponents’ exploratory excavations and drilling. Photo:Carl Weimer.

More damage inflicted on the Lummi sacred ground at Cherry Point by the Gateway Pacific Terminal proponents’ exploratory excavations and drilling. Photo:Carl Weimer.

We see all this. Our people, like most people, play by rules made by others. But Pacific International Terminals, SSA Marine, their parent multinational corporation Carrix, Inc., and their financial backers at Goldman Sachs seem to be partners to a crime, as is their public relations agency, Edelman, the world’s biggest independent PR firm and the shadowy force behind the pro-terminal group Alliance for Northwest Jobs.

In fact, PIT did commit a crime according to Washington State law. It is a misdemeanor in the State of Washington to knowingly disturb or otherwise desecrate a known archaeological site and a Class C felony to knowingly damage a burial ground or grave. They can — and should — be prosecuted on both counts. As one Lummi Council member put it (off the record), “They are well-connected and highly capitalized and paid criminals in suits and ties. Period.” The county did not vigorously prosecute PIT for failure to get the necessary permits. Instead, in August 2011, PIT was notified that they would be penalized $2,000 in fines and $2,400 in administrative fees for code violations related to the failure to acquire permits. Nor has the state diligently prosecuted PIT for violation of the Washington State laws.

The Army Corps of Engineers has also tried their best to look the other way, to justify their own missteps and oversights, and to disingenuously play the good neighbor with the Lummi. But everyone is not fooled. The Corps is a permitting agency. They are also our Trustee. They wish to be seen as good neighbors, but have shown themselves to be untrustworthy. We were reminded that Isaac Stevens was a Colonel, as was George Custer. Although many of our people are veterans who served bravely and proudly in all of America’s wars, in this situation the Army Corps is not our friend. We do not need a friend in Colonel Estok, the Seattle district commander of the Army Corps of Engineers; we need a Trustee whom we can trust.

The United States Army Corps of Engineers, with questionable legal authority in this instance, has asked the Lummi Tribe to sign a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) to bring SSA/PIT “into compliance.” The Corps of Engineers in Seattle repeatedly misrepresents the MOA to our people (see the timeline to the right for additional detail), uses twisted logic to explain its authority regarding the violation of archaeological sites on state and private lands, fails to fully communicate the situation to their superiors in Washington, D.C., threatens to go forward with or without the Lummi on the MOA, and threatens to issue an after-the-fact permit for the wetlands violation if we do not cooperate. They may yet succeed in this unconscionable pressure tactic, but the whole process is a study in dissembling and dysfunction.

Coal Dust on the American Dream

It is an old, old story of coercion, with new players, big money, and co-option of a regulator by those whom it should be regulating. The Indians are in the way of “progress”: Indians and their sacred grounds, their burial grounds, their customary way of life, and Indians who value family and future generations above short-term profit. The naked truth is, the proposal by PIT/SSA and its partners for coal shipment, storage, and transport would cost us all — Indian and non-Indian — dearly here, and across the Pacific Northwest, but handsomely profit a handful of shareholders on the east coast.

I sometimes think I’m dreaming. I fail to see how any responsible public official — elected or otherwise — could possibly support this madness. Why? Because of the promise of jobs? Can anyone be so naïve as to think that this is not just another in a long line of promises surely made to be broken?

Here are the facts of the matter, the massive public relations campaign of PIT notwithstanding:

- The desecration of one of our oldest village sites and the first archaeological site to be placed on the Washington State Register of Historic Places

- Up to 1.5 billion gallons of water per year needed to water down the coal piles

- Millions of gallons of toxic runoff inevitably finding its way to Puget Sound from the proposed terminal

- Over 400 cape-sized ships (1,000 feet long) per year departing the Cherry Point terminal with 287,000 dead weight tons of coal per ship (fully loaded, each ship takes up to six miles to stop)

- Eighteen trains per day, each 1½ miles long arriving and departing the terminal

- At least 60,000 pounds of coal dust per train deposited along the rail line from Powder River and at least 500 tons of coal deposits every year in the Cherry Point Aquatic Reserve

- Assuming a full build-out, 213 full time jobs at the terminal (but note that the Westshore coal terminal at Roberts Bank, Delta, British Columbia to the north has made a consistent policy of automating their operations to reduce labor costs)

- Endangering a Lummi fishing fleet that includes 450 vessels and 1,000 tribal members; in the Salish Sea 3,000 people are directly employed by the fishing industry as well as 28,000 related jobs in an industry that generates $3.8 billion annually in economic benefits

The Lummi recognize the land, water, and air will be contaminated. This pollution will have a cascading effect throughout our natural environment. The river runs dry for corporate profit and the salmon cannot swim upstream during the lowest flow periods of the year. The salmon die because they cannot get to the spawning grounds. Offshore, the fragile herring population will be immediately assaulted by the dust and toxins. Crabs in the area will be poisoned as well. Who will ultimately pay the price for the inevitable damages done to the environment from this proposed terminal? Our people and the residents of Whatcom County have seen this many, many times before. The answer comes down the Nooksack River in the form of massive debris flows and silt loads from a history of clear-cutting in the forests. It can be found at the bottom of Bellingham Bay with the left-over poisons from Georgia Pacific. It is evident in the fouled waters off Point Roberts where our fishing nets are turned gray from the pollution from the Westshore coal terminal at Tsawwassen.

Fortunately, the Lummi Nation has the support of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians (ATNI) in its opposition to the Gateway Pacific Terminal proposal. ATNI represents 57 Pacific Northwest tribes in five states. Many of these tribes will be directly impacted by the coal trains. Several thousand Treaty Indians along the Columbia River and within the Salish Sea will have unavoidable and permanent damage done to their treaty fishing rights. We know and understand treaty rights would be lost for generations. After all these years, we perceive that it is still all about getting the Indians out of the way.

The offer is jobs and contamination now or movement toward less global warming tomorrow. Jobs and income opportunity are something near to home. For the average American global warming is a distant concern, out there somewhere. They are struggling to get by, dogpaddling to the American Dream. They strive to reach a moderate living income for their families, which is possible only if both parents are working. What many Americans are learning is that the top 1 percent own 42 percent of the (non-home) financial wealth in the United States; the bottom 80 percent own less than 5 percent. Among the top 100 major industrial nations, the United States ranks ninety-third in income equality.14

The corporations have a virtual strangle-hold on the American continent and now grip the Constitution through the fiction of corporate rights. They are now absurdly recognized as “persons” with standing in a court of law. These corporate persons have shamelessly covered the continent in toxic pollutants through short-sighted and self-interested industrial development. Today they are super-citizens that feed the rich and deprive the majority of Americans the basic necessities of life. These are the bad actors that hope to convince us that they have the right to develop Cherry Point — and we, the citizens, need these jobs — regardless of the environmental consequences and costs. It is a formula that has served them well in the past: the privatization of profit and the socialization of cost.

We Are “The People”

The Constitution is for “We the People” not “We the Corporations.” Sovereignty derives from the many, not the few. American Constitutional sovereignty has been popularly-based since 1787. The incorporated states tried to define “control” under the Articles of Confederation, but failed because the People did not agree. They wanted a government selected by and for the people, exercising powers delegated from the people, and held accountable to the people. The corporations involved in the coal port proposal have joined together to translate their dream into profits. They have persuaded Congressman Larsen, among others, to join them. Interestingly, he received far more in contributions from SSA Marine than any other representative in the Washington congressional delegation. Perhaps this is a coincidence, but it does not seem likely. Tribal leaders report that neither he nor his staff will give them the time of day on this issue. His mind is made up. Could this be the result of corporate influence peddling? They pave the political road with corporate contributions. Politicians are held accountable to them, not “We the People.”

We expect SSA Marine and PIT to try to influence the upcoming tribal elections in the Lummi Nation, just as they will be pouring millions into the Whatcom County elections through their surrogates. We the People are merely a nuisance to them whom they believe are easily bought and sold. This is but one in a long line of outrages of these “corporate neighbors.”

The Lummi people, their Chief, and their leadership are endowed with enough traditional knowledge and teachings to resist these temptations. We are kinship-based, not corporate. Nature is a gift, not a commodity. There are a few individuals in our community singing from the Pacific International Terminals songbook, a songbook with false lyrics and false notes for false singers, and they can unfortunately be found in any community, as can those who spill and spread ill-will and mistrust by feeding off fear and ignorance. But our people are, first and foremost, tribally-oriented fishermen. We will always aspire to the dream of restoring the Salish Sea, the streams and rivers, and the salmon runs, and preventing or, if need be, undoing the damage of our corporate “neighbors.” We will also always believe in the spirit of hope and cooperation in our relations with the citizens of Whatcom County who share our concern for the long-term health of this place we all call home.

Our Sacred Obligation

Responding to the project’s permitting process for the proposed terminal is like cutting a diamond. The owners want to harvest it, cut it, and polish it, legally, economically, and politically. Internal documents of PIT reveal that in 2012 they remained confident they could have the terminal up and operating in five years — maybe even four.15 We need to strike at the flaws and shatter this false economic diamond. This is a false diamond for its supposed benefits are dwarfed by the hidden as well as externalized costs resulting from poisoning the land, denaturing the waters, destroying historic sites, desecrating burial grounds, and damaging the health of the people.

Author Jewell Praying Wolf James speaks to supporters at the gathering at the Bellingham Unitarian Fellowship on May 27, 2013. The Lummi Nation Sovereignty and Treaty Protection Office called two separate meetings of Bellingham clergy and activists to discuss Tribal concerns about Cherry Point and the proposed Gateway Pacific Coal Terminal. Photo: Lummi Nation Sovereignty and Treaty Protection Office.

Author Jewell Praying Wolf James speaks to supporters at the gathering at the Bellingham Unitarian Fellowship on May 27, 2013. The Lummi Nation Sovereignty and Treaty Protection Office called two separate meetings of Bellingham clergy and activists to discuss Tribal concerns about Cherry Point and the proposed Gateway Pacific Coal Terminal. Photo: Lummi Nation Sovereignty and Treaty Protection Office.

I often hear people ask: What can I do to promote a healthy environment and push back against the juggernaut of corporate power? Goldman Sachs alone has almost $1 trillion in assets!16 People feel powerless, overwhelmed, and unsure what to do. The answer is here, before us, in preventing this mega-project from going forward. We can and must stop it and put in its place a vision of responsible long-term stewardship of the land and water. We don’t need to be hypnotized by their narrative or to become a corporate colony of global finance and Wall Street investors. We are the people. We have to unite to preserve the ecological vitality of the Pacific Northwest. This is our home. We must commit to stop toxic dumping into public lands, air, and waters. We must demand that our lawmakers stop giving away public resources for private gain. But we can only do this through coalition-building. It has always been true, and is true, today.

We respectfully call upon the tribes, the non-Indian community, civic organizations, professional organizations, the business community, the faith-based communities, non-governmental organizations, and elected officials to put aside any differences for the sake of the Creation. Most importantly, we are asking that the general public take the time to become informed on the magnitude and madness of this proposal. Let our voices be heard for the benefit of our children and our children’s children — and to honor the Creation.

Now is the time. This is the place. We are the ones called to this duty in the name of our collective Xa xalh Xechnging (“sacred obligation”).

Endnotes

- For an interesting background history, see http://www.ratical.org/many_worlds/6Nations/EoL/chp8.html.

- Lewis Hanke, All Mankind is One: A Study of the Disputation Between Bartolomé de LasCasas and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda in 1550 on the Intellectual and Religious Capacity of theAmerican Indian (Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 1974), 67.

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Peters) 1 (1831).

- Johnson v. M’Intosh, 21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 543 (1823).

- Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States, 348 U.S. 272 (1955).

- For a concise video of Johnson v. M’Intosh, see http://freedom.ou.edu/freedom-101-2-ep-12-johnson-v-mintosh/.

- Anthony Pagden, European Encounters with the New World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), p. 117.

- Ibid.

- See http://www.dailykos.com/story/2013/04/14/1200994/-Native-schools-and-stolen-generations-U-S-and-Canada for details of the history.

- See http://nativeamericanhistory.about.com/od/Law/a/The-History-Behind-The-Cobell-Case.htm for a brief summary of the Cobell case.

- See http://cantonasylumforinsaneindians.com/history_blog/tag/religious-crimes-code-of-1883 for information.

- See the National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/nagpra/mandates/25usc3001etseq.htm , for the law, and see the Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies, University of Arkansas, http://cast.uark.edu/home/research/archaeology-and-historic-preservation/archaeological-informatics/national-nagpra-database.html, for information about the database associated with implementation of the law.

- For additional information about the Salish Sea, and the herring and salmon fisheries, see http://www.whatcomwatch.org/pdf_content/OurLivingJewelOct2012.pdf.

- G. William Domhoff, “Wealth, Income and Power,” in Who Rules America (http://www2.ucsc.edu/whorulesamerica/power/wealth.html).

- The proponents’ submitted documents state that the initial construction phase would take two years and that “the first commodities would be moved through the facility in 2016.” This information can be found at the Whatcom County Planning and Development Services website: http://www.co.whatcom.wa.us/pds/plan/current/gpt-ssa/pdf/20120319-permit-submittal.pdf.

- See http://www.goldmansachs.com/media-relations/press-releases/current/pdfs/2012-q4-results.pdf.

Help Us Carry the Voices: The Kwel hoy’ Totem Pole Journey

In September of 2013 a totem pole, being carved by Lummi tribal members and Master Carver Jewell James, will be transported 1,500 miles from the Powder River basin, following the rail lines, all the way to Cherry Point. Mr. James carved and delivered totem poles to each of the 9/11 sites to help heal the American Nation. The totem pole will be blessed by tribes all along the journey, and will serve as a symbol uniting the tribes, small towns, communities, and cities opposed to the project. The journey will provide an opportunity for communities and tribes to tell their story, hear how this project will impact others, unify the west, and help “draw the line” (Kwel hoy’). The journey will be covered by local, regional, and national press, and will help unite these communities and raise the voices of those who believe in the message of our sacred obligation. To learn more or to make a donation to the journey, please go to www.totempolejourney.com or call 800-670-6252. All donations are tax-deductible.

Damages to Cherry Point

1. SSA Clears Trees, Fills Wetlands, Disturbs Cultural Areas Without Permits.

July 16, 2011: Whatcom County Planning and Development Services (PDS) received a report of extensive clearing and grading activity at the site for the proposed Gateway Pacific Terminal.

August 2, 2011: PDS issued a Notice of Violation DOC A to Pacific International Terminals, a subsidiary of SSA Marine (SSA). The county reissued the notice on August 17. The violation involved clearing of approximately 23,132 lineal feet (9.1 acres) for access paths/roads in uplands and in wetland forest and shrub areas (approximately 2.8 acres of wetlands impacts and .98 acres of wetland buffers).

July 30, 2011: SSA issued a press release DOC B, acknowledging that its contractors conducted work on the site, digging approximately 70 core-sample holes. The press release did not mention the 4.4 miles of roads (9.1 acres) or the 3.8 acres of wetlands and buffers cleared by SSA, according to the County.

September 12, 2011: Whatcom County issued a Mitigated Determination of Nonsignificance (MDNS) DOC C for the SSA clearing violations.

2. DNR Determines the Disturbance Is Not Actually Part of the Project.

August 12, 2011: DNR issued a “Notice to Comply” DOC D documenting numerous violations of the Forest Practices Act, including pulling of stumps and timber harvesting in wetlands without a permit.1 DNR did not issue a finding of an illegal “conversion,” asserting that a conversion only occurs when SSA actually obtains permit approvals and starts constructing the project. (Note: The Department of Ecology also issued notification of violations under the Clean Water Act.)

Had DNR found that SSA engaged in an unlawful “conversion,” Whatcom County could have imposed a six-year moratorium on approving any application for land development on the site. Whatcom County Code 20.80.738(1)(a)(iii). This would have precluded development of the coal terminal proposed by SSA for up to a decade, factoring in the time from application to final approval.

In summary: DNR determined that the project had not yet actually begun; the geotechnical exploration was not the same as starting a project; and conversion of land from forestry uses did not actually occur because “the project” had not begun. DNR’s interpretation was cited in a letter DOC F from County Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Royce Buckingham explaining why the county would not impose a moratorium.

Although DNR’s notice stated that SSA conducted forest practices without a permit, DNR did not require SSA to obtain the missing permit. DNR merely required SSA to reforest the site in three years if it did not go through with the proposed marine terminal construction. Relying on DNR’s determination of “no conversion,” Whatcom County staff did not seek a six-year moratorium.

3. Whatcom County Requires an “MOA” With Tribes Prior to Further Work.

August 15, 2011: SSA filed a SEPA Checklist with Whatcom County, indicating SSA’s intent to convert the land to another land use. SSA disclosed that its illegal grading and clearing had disturbed items of Native American archeological significance.

September 12, 2011: PDS issued a Mitigated Determination of Nonsignificance (MDNS) under the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA). While the first version of this document outlined conditions for restoration of disturbed critical areas and buffers, it made no mention of the archeological disturbance. DOC C

October 5, 2011: The Washington State Office of Archeology and Historical Preservation (AHP) sent the county a letter objecting to the MDNS. OAHP cited the archeological disturbance and stated that, under state law, no further work could be conducted on-site until a permit was issued by their office (if Whatcom County is the lead agency), or until a “Memorandum of Agreement” (MOA) was signed by affected Tribes under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (36 CFR 800), if the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is lead agency.

October 10, 2011: Whatcom County PDS added conditions to the MDNS in response to the OAHP letter DOC G, to require either the state permit or the Memorandum of Agreement, if the Army Corps of Engineers is lead agency prior to further site disturbance. SSA did not appeal the county’s SEPA MDNS or revised conditions. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers asserted lead agency for purposes of the cultural disturbance.

Under Whatcom County Code 20.94.080(2), all future permits and approvals that may pertain to Title 20 (Zoning Code) may be denied for the site until compliance has been achieved, in the satisfaction of the zoning administrator, or his designee. Thus, until the land and cultural disturbance violations are resolved in accordance with the county’s SEPA condition, SSA’s permit applications are subject to denial. In light of the Corps’ lead agency, this means that Whatcom County can deny SSA’s project permits, until an MOA is agreed to for the cultural disturbance.