by Wendy Harris

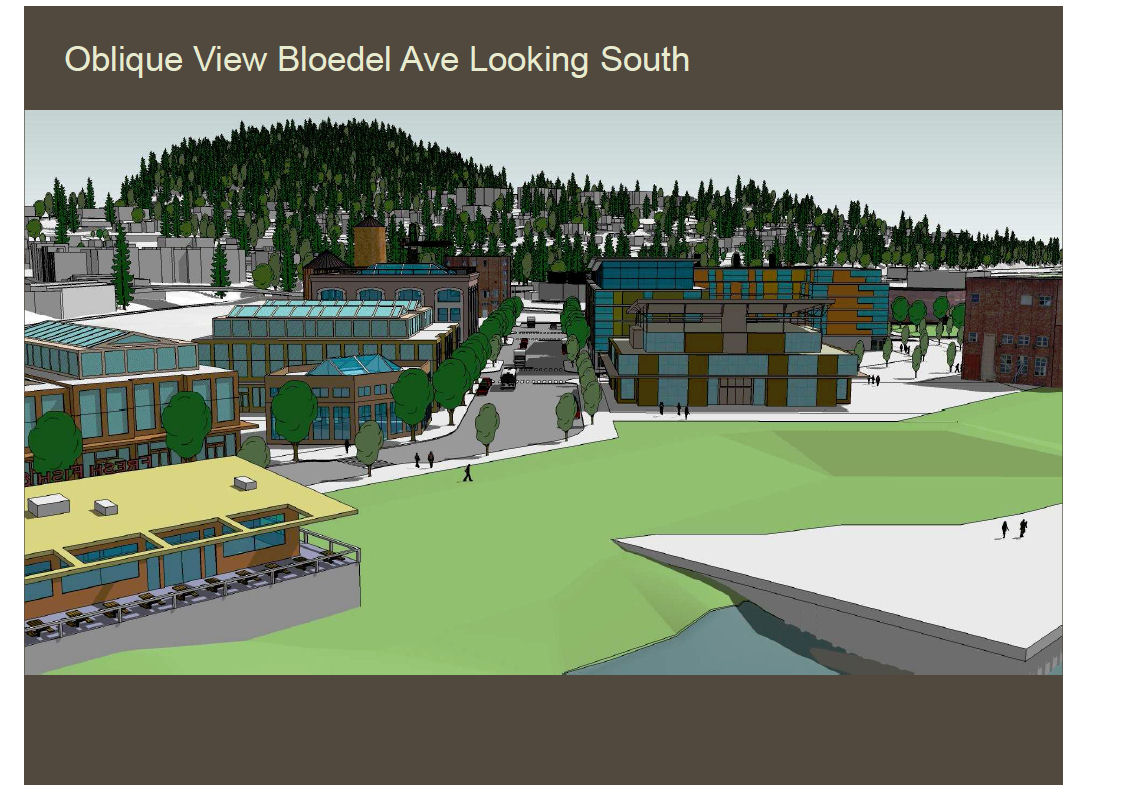

An artist’s conception of the waterfront redevelopment that the city of Bellingham is planning for the waterfront area near the Whatcom Creek outfall. Image: City of Bellingham.

An artist’s conception of the waterfront redevelopment that the city of Bellingham is planning for the waterfront area near the Whatcom Creek outfall. Image: City of Bellingham.

In 2003, the City of Bellingham and the Port of Bellingham became partners in a joint project to restore and develop the Bellingham Bay waterfront. The public was provided opportunity to comment on waterfront plans, which continued to evolve and change over time. Much of this occurred as part of an informal process. The last opportunity for public input was in 2010. Since that time, the public review process has been on hold.

A revised draft waterfront proposal was released by the city and port on November 15, 2012, and finalized documents were issued a month later. The revised waterfront plans are being reviewed by the Planning Commission, which listened to public comment during two public hearings in March. After the Planning Commission completes its review, it will issue a recommendation for City Council consideration.

I attended the March 14, 2013, meeting of the Bellingham Planning Commission, where the city and port administrative staff (“staff”) provided a general overview of the new waterfront proposal. I was not a resident during the most active years of planning, but I knew the plans required some difficult decisions. I was hoping to hear a discussion of the planning options that were available, perhaps a review of the history of the process, and an explanation of why staff made the choices selected in the final waterfront plans.

Instead, I heard a slick PR presentation that promoted the staff’s proposal, ignoring issues of conflict and controversy.

Transparency and informed public consent requires a forthright disclosure of the strengths and weaknesses in a comprehensive planning proposal.

Staff advocated, rather than informed. I could just as easily have been attending a sales presentation.

The Planning Commission was advised that the new waterfront plan reflected extensive public process and incorporated community values. This assertion was contradicted one week later, March 21, 2013, during the first public hearing before the Planning Commission. Flawed public process was a leitmotif that evening, reflected in comment after comment by the public.1

The city and port responded with evidence believed to be proof of public process. The city’s waterfront website contains a “quick link” to the public process.2 The link leads to a list of the 2013 meetings for five citizen-appointed advisory boards, four of whom have reviewed or will review the revised waterfront plans, including the Planning Commission. The city emphasized, in response to public comment monitored by a public comment tracker, the roles of the Waterfront Futures Group and the Waterfront Advisory Group in promoting public input.3

The staff’s response is not on point. Public concerns are less about the opportunity to provide input and more about the failure to see that input reflected in the end product. For example, while the city is to be highly commended for creating a public comment tracker, it has responded to virtually all public requests for waterfront plan modification reflected in the public comment tracker with “NC,” for “no change.”

An important issue is not being addressed: prior public process related to different versions of waterfront plan proposals. The current version contains some significant amendments that reflect changes in market conditions impacting real estate and job development. Staff can not assume that, while its planning proposal has changed to reflect updated information, public opinion has remained static. Outdated public process does not protect the public’s due process rights.

Nor was this what the public was originally promised. On November 15, 2012, Mayor Kelli Linville was quoted in The Bellingham Herald as follows:

We look forward to putting the final touches on proposed agreements and getting them ready for public and legislative review….We expect these proposals to go through a robust public input process beginning early next year. When that time comes the public will have available to them all the information they need to participate in decisions about how the waterfront will develop.”4

It appears that the extent of this “robust public input”, at least before a final proposal is forwarded to the City Council, is limited to two public hearings before the Planning Commission, scheduled without any effort to educate the public about the new revisions.

And from the comments that were received during the two public hearings, proposed waterfront plans continue to contradict the public’s interest in high clean-up standards, restored shorelines and healthy ecosystem functions, well-connected trails, abundant parks, retained scenic vistas and historic preservation. It is time to examine the myth of waterfront public participation.

Predetermination of Waterfront Projects

Staff has obtained funding and City Council approval for specific waterfront plan components while the waterfront planning process is still in progress. Comprehensive city planning documents such as the annual budget, Capital Facilities Plans and Transportation Improvement Plan have been amended to include specific projects reflected in the proposed waterfront plans.

Staff convinced the City Council, sometimes against its better judgment, that this type of piecemeal process is appropriate because the waterfront projects are general and details will be determined later, allowing room for changes based on public opinion. Is there really anyone naive enough to think that the public can influence a pre-funded and pre-approved project?

A recent example of the problem is reflected in the $1.5 million grant from the Washington State Department of Commerce for development of the Whatcom Waterway sub-area of the waterfront. The city Parks Department, which shares the grant with the port, is using its portion of funds for a new park. The grant was not immediately approved, due to Council Member Jack Weiss’s concern that the grant money was getting ahead of the waterfront planning process and would result in demolition of a historic structure.

The city Economic Development Manager attempted to placate Council by removing specific details from the development agreement with the port, including a map reflecting street placement. Reduced clarity and detail in waterfront plans is not a solution beneficial to comprehensive planning efforts or public transparency. Staff argues that proposing open and nonspecific plans increases future planning flexibility, while allowing for public input. I argue that it increases the city administration’s disingenuity, leaving them less accountable and less likely to engage in comprehensive planning efforts.

The city Parks Department, with council approval, amended the city’s Capital Facilities Plan to include an interim trail around the perimeter of the Aeration Stabilization Basin (ASB). This is rather significant, because development of the ASB has been one of the most-contested issues of the waterfront planning process. The current proposal reflects development of a new marina, a proposal that significantly raises the cost of waterfront cleanup and redevelopment.

The port has been steadfastly committed to its vision of a “clean ocean marina.” At the same time, a majority of residents have opposed what they characterize as a “luxury yacht marina,” believing the site better used for waste water and/or storm water management, as a depository for the contaminated material removed from waterfront cleanup sites, or as a large public park.

The port will not be ready to develop the marina for an estimated 20 years or more. The interim ASB trail supports the proposed marina by providing some public use of the site while it otherwise sits undeveloped. $500,000 of REET (Real Estate Excise Tax revenues) funds was allocated for the ASB interim trail, despite the notoriety surrounding the marina and the lack of finality for proposed waterfront plans.

And in case the reader has lingering doubts about predetermination of certain waterfront projects, the port is proudly advertising the new waterfront marina on its website. Why wait for formal approval when the results are already known? That is why an April 1, 2013, article in the Pacific Waterfront Magazine stated, in relevant part:

Bellingham’s waterfront redevelopment plans include a new downtown marina. The port will remove more than 400,000 cubic yards of contaminated treatment sludge from a 37-acre wastewater treatment lagoon, which was formerly used to treat process water from a complex pulp, paper and chemical facility. Once the lagoon is cleaned out, it will be converted into a new marina, which will include a mile of public access along the outside of the breakwater (i.e., the above-referenced ASB interim trail) and shorelines reshaped to support salmon recovery efforts.

Public Process Problems Not New

Issues regarding public participation have plagued waterfront planning from the very beginning. The Waterfront Advisory Group (WAG) minutes from November 28, 2005, reflect public process complaints.5 The problem was acknowledged by WAG in minutes from a June 20, 2007 meeting, which stated:

There were concerns that during planning process it is hard to see the results of input. Public comment is accepted, but people want comments heard and acknowledged. They want a response. Once there is a work product, it should reflect the public comments. People should see how they impact a decision. WAG members encouraged citizens to attend Port Commission and City Council meetings.6

There was such a pronounced perception that the public was being excluded from waterfront plan development that it led to formation of activist groups, including Friends of Whatcom County and the Bellingham Bay Foundation.

Discontent with waterfront plans, dating back to the time the waterfront was referred to as “New Whatcom,” is implicit in alternative waterfront plans submitted to the city, reflected as “independent design concept proposals for New Whatcom.” Proposals were submitted by the Bellingham Bay Foundation, WAG member John Blethen, and 2020 Engineering, among others.

Conflict Over Clean-up Standards

The public’s strong preference for the most protective (and most expensive) clean-up method, off-site removal of contaminants, has consistently been in conflict with the port’s use of interim (i.e, temporary and partial) site clean-ups and less protective (and less expensive) capping and on-site containment.

In 2000, the Bellingham Bay Demonstration Pilot Project, a multi-stakeholder group co-managed by the Washington Department of Ecology, published a report recommending that mercury contamination in the Whatcom Waterway be dredged. In 2006, in response to port plans to cap the mercury, a frustrated community mobilized itself.

The Bellingham Bay Foundation formed People for a Healthy Bay and gathered 6,400 signatures in 20 days for an initiative to require the highest level of clean-up for the Whatcom Waterway. The initiative was supported by polling data indicating that the public’s primary concern was a clean, safe waterfront. The city successfully sued to keep the initiative off the ballot, and the site has remained contaminated all these years.

An interim action for the Whatcom Waterway is only now underway. The port is removing mercury from three small areas with exceedingly high levels of mercury contamination. However, there are no immediate plans for clean-up of the remaining mercury, which in some areas exceeds safe exposure levels up to fifty fold.

The public remains largely unaware of a potential problem lurking within the policy provisions of the revised waterfront plan. The “beneficial reuse” provisions from the Model Toxic Control Act have been quietly incorporated into revised waterfront plans. While the stated goal – recycling waste in a manner that protects public safety – is admirable, the policy can be misused as an inexpensive method of toxic waste disposal.

This has already occurred, as evidenced by the dioxin mountain on the Cornwall Avenue landfill site. Sediment dredged from Squalicum Harbor, contaminated with dioxin exceeding safe exposure standards, was dumped and will be capped with clean soil, upon which the site will be developed.

The revised waterfront plans require raising the height of the downtown waterfront area by at least 10 feet, creating a pressing need for a cheap source of fill. I expect to see more use of contaminated dredged soil in the waterfront. This is not a policy that staff has been disclosing in its public promotion of the revised proposal plans.

Citizen Advisory Commissions

As proof of public process, the city staff notes in its staff report the work of citizen-appointed advisory boards, particularly the Waterfront Futures Group (WFG) and the Waterfront Advisory Group (WAG), as well as the Transportation Commission, Parks and Recreational Advisory Board, the Historic Preservation Commission and the Planning Commission, noting that these citizen boards “reviewed various aspects of the Waterfront District Plans.”

Citizens appointed to these advisory groups are hand-picked by the Mayor (and the port for the WFG and WAG), and often reflect the influence of particular stakeholder groups rather than the concerns of the public at large. Some of these advisory groups have a limited scope of review, which creates some conflict with a comprehensive planning process that requires balancing and prioritizing different needs.

While the recommendations of citizen advisory groups are often irreplaceable and invaluable, they have serious limitations and have never been intended as a substitute for full public participation.

Nor have these citizen advisory groups been allowed to play an active role in shaping and guiding the waterfront plan provisions, which is the heart of a public input process. Their role in the current waterfront proposal is limited to a post-draft review function. For example, the Waterfront Advisory Group was reconvened in November 2012, after a two-year hiatus, for the purpose of reviewing the changes made by the staff in its absence.

Some of these advisory groups do not support many of the proposed revisions. In particular, I suggest the reader review the comments submitted by the Transportation Committee and the Historic Preservation Committee to make his or her own assessment of the adequacy of public process.7

Public Process Requires Public Education

Given the complexity of the waterfront planning process and the multitude of revised documents that were released in December, several public meetings should be scheduled to cover specific waterfront sub-topics. Normally, public information meetings are scheduled for complex and/or important planning proposals. It is unclear why this has not occurred here. Work sessions were scheduled to provide additional information to the Planning Commissioners, but Planning Commission’s public hearings were scheduled prior to these work sessions, depriving the public of the right to either listen or learn.

The heart of the proposal is the Waterfront District Sub-Area Plan, otherwise known as a “master plan,” which is intended to provide a “big picture” overview of proposed waterfront plans.8 It includes five waterfront sub-districts with different land use plans and zoning requirements, and five development phases that will take at least 25 years to complete. It covers a broad scope of comprehensive planning issues.

Specifics for how the waterfront policies and goals will be implemented are written into the Waterfront District development standards and the Waterfront District design standards.9 It could not be expected that the average citizen (i.e, without special training and background) could readily understand these documents. It is also important to have an understanding of the 2013 Bellingham Shoreline Master Plan.

A planned action ordinance (PAO) is being included in the revised waterfront plans for the first time, and the city’s prior refusal to sign this document was a source of friction between the city and port.10 This document impacts important public rights, but was not discussed at the staff presentation to the Planning Commission.

The PAO restricts the public’s rights to impose updated environmental standards on future waterfront developers. Developers obtain vested rights to mitigate harmful impacts based on the analysis referenced in the 2010 Waterfront Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). The EIS becomes dated over time, but there is no requirement for periodic update, even though waterfront development is expected to stretch over a number of decades. The PAO also revises and limits the public rights under the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA).

Public process does not exist unless the public has been provided with adequate education. It is not sufficient to simply release a large multitude of complex and technical documents, many of which contain significant policy provisions unlikely to be understood by the average citizen. Implicit in the concept of public process is the obligation to provide sufficient education for informed public comment.

Summary

The city and the port have attempted to paint a rosy picture of a robust, extensive public participation process that does not hold up under closer inspection. Much of this process was relevant to prior versions of waterfront proposals, and — even then — there were complaints about inadequate public process. Problems with public process appear to be confirmed through waterfront plan provisions that are in clear conflict with public opinion on important issues, including clean-up standards and development of the ASB.

There has been no public review process over the last few years, during which time the port and city were revising waterfront plans. Public input has been restricted to a review function, and this review function has limited value because some of the proposed waterfront plans have already been funded and approved in separate processes. Numerous complex plans and documents for the revised proposal were released only a few months ago, and two public hearings before the Planning Commission were hurriedly scheduled, leaving no time for public education and discussion, despite new policies with important impacts.

The waterfront public process is but a shell, as empty as our deteriorating historic icons on the waterfront. It is great for show but has little substance and, with only a little bit of pressure, is likely to crumble.

Footnotes

1. City and Port presentation to Planning Commission on March 14, 2013 on Waterfront District Redevelopment at http://www.cob.org/documents/planning/waterfront/2013-03-14-pc-ppt-presenation.pdf; See also video at http://www.cob.org/services/education/btv10/videos/boards-commissions/2013-03-14-planning-commission.aspx.

2. http://www.cob.org/services/planning/waterfront/public-process.aspx

3. City Waterfront District Comment Tracker, Public Comment Through March 29. http://www.cob.org/documents/planning/boards-commissions/planning-commission/4-11-13/comment-tracker-cont.pdf; Planning Commission Staff Report issued for March 21, 3013 public hearing, http://www.cob.org/documents/planning/boards-commissions/planning-commission/3-21-13/staff-report.pdf

4. November 15, 2012 article from Bellingham Herald at http://www.thenewstribune.com/2012/11/15/2368997/port-bellingham-release-long-awaited.html

5. WAG minutes from November 28, 2005 at, http://www.cob.org/cob/wagmin.nsf/50999134738287ed8825733200620fb5/f3b399b301506f3a8825724c0000699d!OpenDocument;

6. WAG minutes from June 20, 200 at, http://www.cob.org/cob/wagmin.nsf/50999134738287ed8825733200620fb5/5e6e93060c2fe78a8825737d00790789!OpenDocument

7. Citizen advisory group comments at http://www.cob.org/documents/planning/boards-commissions/planning-commission/3-21-13/attachment-1.pdf

8. Waterfront District Draft Sub-Area Plan, 2012, at http://www.cob.org/documents/planning/waterfront/2012-12-17-entire-subarea-plan.pdf.

9. Waterfront District Draft Development Regulations, 2012 at http://www.cob.org/documents/planning/waterfront/2012-12-17-development-regulations.pdf and Waterfront District Draft Design Standards, 2012 at http://www.cob.org/documents/planning/waterfront/2012-12-17-design-standards.pdf

10. Planned Action Ordinance, at http://www.cob.org/documents/planning/waterfront/2012-12-17-planned-action-ordinance.pdf

Wendy Harris is a retired citizen who comments on development, mitigation and environmental impacts.